In 2008, a billion gallons of toxic sludge spewed across 300 acres of Tennessee in the middle of the night. It was just before Christmas. At the time, Jared Sullivan was in high school and remembers the disaster. For over fifty years a power company called the Tennessee Valley Authority – or the TVA – had been burning coal at a power plant near Jared’s hometown. Burning all that coal helped bring electricity to the region, but it also created a mountain of ashen waste. Over the years, this mountain grew to be 60 ft high and 84 acres wide. And on December 22, 2008, the earthen embankment that contained this mountain of waste collapsed. A lethal wave of coal sludge inundated the countryside.This disaster came to be known as the Kingston Coal Ash Spill. And the culprit wasn’t a private company – it was the TVA, a federally owned electricity provider that had been set up by the government during the New Deal. Immediately after the disaster, 900 workers from around the country descended on the site to help clean it up. Everyone expected that they’d find bodies under the sludge — it was a miracle that no one died that night. The real tragedy came years later, when many of the workers in charge of the clean-up fell sick and even died from health issues caused by inhaling the toxins found in coal-ash. The fallout from what happened at the Kingston Coal Plant led Jared to look more closely at the company in charge, the Tennessee Valley Authority.  The TVA has been around since the 1930s, and today it provides electricity to more than 10 million people. Its presence in the Southeast had a huge impact in transforming the region. The TVA is a backdrop to life as portrayed in Southern literature, film, and music; it’s part of the region’s folklore.

The TVA has been around since the 1930s, and today it provides electricity to more than 10 million people. Its presence in the Southeast had a huge impact in transforming the region. The TVA is a backdrop to life as portrayed in Southern literature, film, and music; it’s part of the region’s folklore.

Jared wrote about the TVA in his new book, Valley So Low: One Lawyer’s Fight for Justice in the Wake of America’s Great Coal Catastrophe. Jared’s book follows the aftermath of the disaster at the Kingston Coal Plant. In doing so, his book reveals an even larger, ongoing American tragedy: how the TVA started out as a mission-driven public institution, but ended up acting like a private for-profit company.

The story of TVA begins with Franklin Roosevelt, who, as a young man, contracted polio and began making trips to Warm Springs, Georgia for treatment. And on those trips, he got a first hand look at how dire the situation was in the Tennessee Valley.

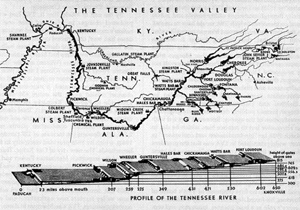

During the 1920s, the Tennessee Valley – which is an area covering nearly all of Tennessee, large chunks of Alabama, Mississippi, and Kentucky, and bits of three other states – was deeply impoverished. Much of the Valley was farmland, but only 3% of these farms had electricity. The area also had a per capita income of less than half of the national average, and about a third of the population was stricken with malaria. On the farms, crops would suffer from an uneven climate. Constant flooding from the Tennessee River would badly damage the soil. Sometimes, the outlook was so bleak that people would abandon their farms altogether.

Congress was aware that something needed to be done. If not simply for the good of the people, then at least to prevent some sort of populist uprising. At the time, big power companies were owned by private holding companies, and they had no financial incentive to provide power to sparsely populated rural area. But as a result, these communities had been stuck without access to power.

Then in 1933, FDR got sworn in as President. And pretty quickly got to work on New Deal programs, one of which was to establish a power company: the Tennessee Valley Authority. Their idea was simple. Electric power should become a public good. Because if you want to improve people’s lives, you have to give them electricity. And for almost a quarter century, the TVA was the single most ambitious public works project in the world. Its mission was to lift the rural South out of poverty by making electricity more accessible to all.

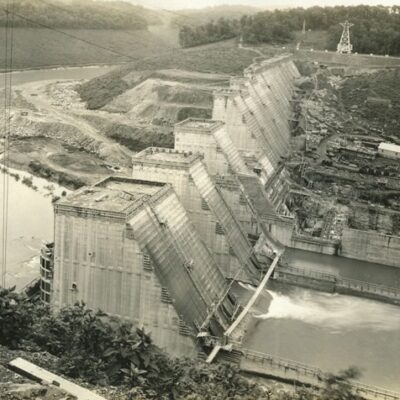

The TVA had three basic goals: to control the Tennessee River, produce power, and improve agriculture. The Tennessee River’s propensity to flood not only damaged farmland, but also sometimes took out entire towns. The goal was to control the river and generate hydroelectric power. And so began the construction of the dams. TVA used eminent domain to remove about 20,000 families from their homesteads. And in their place, they peppered the Valley with dams and brutalist concrete buildings. The first dam they complete is called Norris Dam, just outside of Knoxville.

The TVA had three basic goals: to control the Tennessee River, produce power, and improve agriculture. The Tennessee River’s propensity to flood not only damaged farmland, but also sometimes took out entire towns. The goal was to control the river and generate hydroelectric power. And so began the construction of the dams. TVA used eminent domain to remove about 20,000 families from their homesteads. And in their place, they peppered the Valley with dams and brutalist concrete buildings. The first dam they complete is called Norris Dam, just outside of Knoxville.

In all, TVA built 49 dams, which helped control the river and generate much needed electricity in the South. And in addition to dams, they invested in other projects connected to improving the region. The TVA launched a mobile library service and a ceramics laboratory. It created 13,000 demonstration farms where it taught farmers best practices. The TVA also established a town called Norris. Norris was created to house the workers building the nearby dam. But the town was also a way to show America how cooperative living could work. Norris was completely walkable, with most homes facing each other instead of the street. It included a greenbelt, a school where dam workers could take classes, a post office, a gym, and even a farmers market.

In those first few years, TVA continued to steadily build more and more dams. And in the process, they became the largest producer of electric power in the United States. But these massive government interventions came with a lot of pushback. Wendell Wilkie, president of a large private power company in the South, led the fight against the TVA. Wendell and other power company reps complained bitterly about what they saw as unfair competition. They took the TVA to the Supreme Court and lost, twice.

The TVA was ultimately successful in electrifying the South. The dams tamed the rivers and controlled the floods, which meant healthier soil and more productive farmland. Hydroelectric power was cheap and available, which meant the standard of living increased dramatically. For those who benefitted, it was a social revolution.

For the first time ever, the Tennessee Valley could be lit up after dark. In one of the most conservative regions in the country, millions of people got their electricity from a federal agency that had no shareholders to answer to and no profits to make. And then… something happened that caused the TVA to suddenly change direction.

When WW2 broke out, The TVA, which was a program of the federal government, was suddenly summoned to support the war. Electricity was needed to produce weapons and military equipment, and to build atomic bombs. In fact, the government decided to base the Manhattan Project in Oak Ridge, Tennessee in order to be close to TVA’s power production in the area. What all this meant, though, was that electricity that was previously going to the public was now being siphoned off for war.

Then in the early 1940s, Congress feared a power shortage. They forecasted a dry year ahead, which would affect the river levels throughout the Tennessee Valley, and reduce the effectiveness of the hydroelectric dams. And so the following year, at the government’s urging, and with its funding, the TVA began construction on its first coal-fired power plant. It meant that at least some of the TVA’s power would no longer depend on the weather.

Tennessee stayed in the bomb making business long after WW2. This time, there was a need for uranium enrichment for the Cold War nuclear arsenal. And so, the demand for TVA’s electricity kept going up. At one point, almost half of the TVA’s power production went to the government bomb making facilities in Oak Ridge.

Meanwhile, the South was also seeing an uptick in population. And TVA’s power production couldn’t keep up with the growing demand from both war manufacturers and people living in the Valley. So they started to build more coal power plants. TVA builds 11 of the world’s largest coal-fired power plants to meet these energy demands. Coal plants were cheap and helped the bottom line – it was the easiest way to produce more power under so much pressure.

Then, in 1952, Dwight Eisenhower was elected president, and unlike FDR, he was highly skeptical of TVA as a whole, accusing it of being an example of “creeping socialism.”

Eisenhower’s administration affected TVA’s ability to expand, even though more people were in need of electricity than ever before. Republicans in Congress who were aligned with Eisenhower repeatedly withheld appropriations from TVA. And then, in 1959, Eisenhower cut the TVA off from federal funding entirely. This change meant that the TVA, although owned by the government, needed to start operating like a private corporation in order to finance itself. Since 1959, the TVA has raised capital for its electricity projects by issuing and selling bonds.

This new financial model meant that the TVA began to shift its priorities. What was once FDR’s mission-driven project to lift up the Southeast from poverty shifted its focus to building profit. There was no time or money anymore for cute little walkable towns where you learn how to farm and do ceramics. In this new chapter in TVA history, those social services were the first to fall away. The TVA had to focus on making profits unlike it had before.

Over time, the TVA kept pumping out electricity, producing large quantities of coal powered electricity throughout the Valley. Then they start plotting a transition to nuclear power. In the late 1960’s, the TVA feels the pressure of a wave of new environmental laws. In response, they decide to build 7 jumbo nuclear power plants with 17 nuclear reactors. In 1965, the TVA announced plans for its first nuclear plant. A Knoxville newspaper headline read: “Nuclear Roars at King Coal.” But, their attempt at nuclear is a disaster right from the beginning.

There’s a well documented record of TVA’s nuclear projects running far behind schedule, far over budget, and many times being abandoned altogether. Of the 7 nuclear power plants TVA had intended to build, only three of them were completed. Plans to build the rest fell away after the TVA amassed $10 billion in debt because of their nuclear endeavors.

And then in 1975, TVA’s first nuclear plant in Browns Ferry, Alabama accidentally caught on fire. It forced an emergency shutdown of the plant and causes millions of dollars of damages.

Even though nuclear power is cleaner than coal, it’s a lot more expensive to implement. The TVA didn’t have the money to really invest in this experiment. And its initial nuclear failures, along with other well known nuclear disasters like Three Mile Island, mired public perception of nuclear power’s potential to pivot to cleaner energy.

Throughout the 1980s, the TVA cancelled or put on hold many of these nuclear projects. Some exist today only as blueprints, while others are fragments of concrete and metal that dot the landscape of the Tennessee Valley. The nuclear fiasco has left the TVA with a total debt of nearly $20 billion. All this also meant that the TVA was still heavily relying on coal to produce its power.

In his new book Valley So Low, Jared Sullivan writes more about the consequences of TVA’s decision to stick with coal: that billion gallon toxic sludge eruption at the Kingston Coal Plant in Tennessee.

Comments (1)

Share

Thanks for this show and thanks to Mr Sullivan. I was at the spill site a few days after the spill driving around and taking pictures. TVA attempted to arrest us. Some recognition should be given to United Mountain Defense which distributed clean drinking water to affected residents. They wore full respirators and TVA officials ridiculed them for that. UMD posted many videos on TYou Tube which are still available for those who want to see grassroots activists in action helping their neighbors