In February 2023, over two thousand people took to the streets in Oxford, England to protest their local government. They were wearing yellow vests and chanting slogans about the municipality’s new traffic policies. But most notably, many of them were vocally angry about a new urban planning concept — the “15 Minute City.”

This development baffled many urbanists, since the 15 Minute City is widely understood to be an inoffensive, common sense proposal. “In a nutshell, the 15 Minute City concept is the idea that everything that a person needs within a city should be theoretically reachable within 15 minutes of their home, by either walking or active travel or public transport,” says Feargus O’Sullivan, who has written extensively about this idea for Bloomberg CityLab. “It’s a very simple concept. It’s this idea that basically cities are gonna be healthier if you integrate all their uses together.”

While the concept is popular with city planners and walkable-city advocates, in the last few years, it’s also been the target of right-wing conspiracy theories, protests, and even death threats.

The Concept

The idea behind the 15 Minute City was first laid out by Carlos Moreno, a professor at Sorbonne University in Paris. Moreno had been studying how cities were laid out, and concluded that we’d been doing it all wrong.

For centuries, lots of towns and cities were laid out in a very centralized way, with a town square serving as the city’s hub, encircled by housing and businesses. But in the 20th century, things started changing with the advent of modernism and the rise of figures like Le Corbusier.

After the publication of The Athens Charter in 1933, zoning became a standard part of city planning across North America. Instead of having people live and work in the same place, now, housing, business and industry were sectioned off from one another. This trend emerged around the same time cities were being reshaped to accommodate the rise of car culture. By mid-century, people were being separated from things like work and school and movie theaters, and many of them were taking freeways and expressways to get there.

In 2016, Carlos Moreno proposed an alternative to this kind of planning. His idea for a 15 Minute City was presented as a way to make cities healthier and happier, by providing essentials like health care and schools within a short walking or cycling distance of residential areas. “It’s a very simple concept,” says Feargus O’Sullivan, “and something that Carlos Moreno would admit is not a new concept. This is the direction in which planning has been moving pretty much from the late 20th century, starting back in the sixties, with people like Jane Jacobs.”

Indeed, Moreno’s ideas reflected a growing consensus among progressive urban planners. But it gave them a new language to lay out their ideas. “What I think Carlos Moreno’s idea did that revolutionized this, is it allowed people to sit at the center of that idea,” says O’Sullivan, “because when you talk about a 15 Minute City, you can sit there and say, okay, what’s within 15 minutes of my home? What do I have and what do I lack?”

While this proposal does not include a one-size-fits-all city plan, a number of policies have become associated with the 15 Minute City. This includes limiting car access to downtowns, pedestrianizing car lanes, adding bicycle infrastructure and eliminating single use zoning, to ensure people can live, work and play in the same neighborhood.

Global Popularity

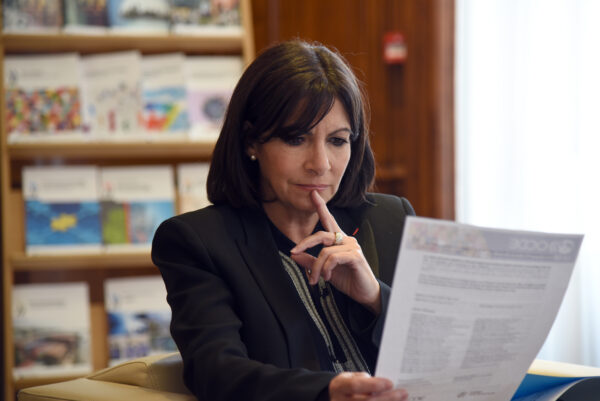

Among the early pioneers of 15 Minute City planning was Shanghai, in China, and Carlos Moreno’s hometown, Paris. In 2014, Anne Hidalgo was elected mayor of the French capital, and a few years later, she made the 15 Minute City central to her city planning, even naming Professor Moreno as an advisor. Since then, Paris has implemented a number of progressive policy ideas. “They reduced car lanes and they increased the number of cycle lanes into the city center,” notes O’Sullivan. “They pedestrianized certain areas. They made other areas much, much less car accessible. And they have tried to increase the green areas by as much as possible.”

Following the advent of the Covid-19 pandemic, a number of big cities followed suit, including Buenos Aires and Busan, South Korea. Even less centralized municipalities – like Cleveland, Ohio, and Edmonton, Alberta – passed city planning initiatives to become more walkable and accessible. In Edmonton, this was inspired by “seeing the trend of more people having to go further and further for work for the services that they need,” according to Erin Rutherford, a city councillor since 2021. “Because our city’s footprint was growing and growing out rather than up,” says Rutherford, “how do we ensure that we’re also building a climate-resilient city, in a city that allows people to not have to drive an hour one way in traffic?”

This global popularity also came with a backlash from dark corners of the internet. “There were a lot of conspiracy theories around lockdowns. There was a lot of people who found lockdowns enormously stressful,” says Feargus O’Sullivan of CityLab, “And they were tending to see the underlying politics of that as inherently sinister. And I think actually that was the springboard, anti lockdown activism bled into anti-15 Minutes Cities activism.”

In early 2023, protestors in Oxford invoked The 15 Minute City, and conspiracy-minded internet figures like Jordan Peterson, Joe Rogan, and Russell Brand all targeted the planning concept. Later that year, it was even condemned by Mark Harper, the British Minister of Transportation, in a speech that sounded quite a bit like the far-right internet chatter around the topic.

Amidst all this, Professor Carlos Moreno and city planners in Oxford faced death threats, and even municipal figures in places like Edmonton faced aggressive rhetoric in city planning meetings. “The reality is it’s not just 15 Minute [Cities],” says councillor Erin Rutherford, about the rhetoric in her local planning meetings. “It’s police funding. It’s so many topics that we’re talking about right now that are creating those visceral responses from folks.”

The Future of the 15 Minute City

Ultimately, many cities went ahead with their plans to foster more walkable, liveable cities, but abandoned the name “15 Minute Cities” in the process. “You can get rid of the 15 Minute City concept and keep the policies, because all it is is literally thinking about what’s in your area within a 15 minute radius of your home,” says O’Sullivan. “Get rid of that concept, you can still work towards low traffic neighborhoods, greater pedestrianization, tree planting, all of these things that individually aren’t automatically going to face the same kind of resistance.”

By contrast, other cities, including Edmonton, went ahead with their progressive city plans, and kept the name intact. “I think we’re almost doing a disservice stopping calling it a 15 Minute City,” says Councillor Rutherford, “because the more we do call it 15 Minute City, and the more nothing substantially changes in people’s lives, the more that that becomes, oh, my fears didn’t come to reality.” In 2024, Edmonton passed an updated city plan, based on concepts from the 15 Minute City.

Today, Professor Carlos Moreno says the rhetoric and tensions around his planning concept have calmed down, and now more than 50 municipalities worldwide are following his urban planning philosophy. He’s also published a book on the concept, entitled The 15 Minute City, to continue evangelizing for more walkable, sustainable neighborhood planning.

Comments (7)

Share

The discussion of the opposition was a bit one-sided. You focused on a certain group that was, to say the least, questionable. You did not address some of the other issues.

You mention that cars have not been around very long in terms of the history of the city, but you fail to note that cars have been around far longer than modern urban planning! Most of what I dislike in North American cities is the result of restrictive planning regulations, whether it’s expansive parking lots or segregated zoning. Most of what I appreciate about old sections of towns, whether European or American, is the result of allowing urban areas to develop more organically, and interestingly, these areas naturally became what we now call 15-minute cities.

Urban planning has now entered a new phase of studying how towns used to grow organically so that they can zone in a similar manner to create 15-minute cities. This raises a fundamental question: Why not simply let towns grow organically and eliminate the need for urban planners?

Urban planning is also prone to corruption, and the 15-minute city concept potentially increases opportunities for petty bureaucratic interference. Consider the absurd scenario: “Sorry, only one grocery store is allowed in this area.” This type of restrictive zoning was not adequately addressed in the previous discussion.

Roman, I have been a fan for many years. This is truly my favorite podcast. But just a bit of feedback from a fan who has never voted Republican, is not far-right, nor a conspiracy theorist. This episode came across pretty arrogant and bigoted. There are many examples of ways that overly top-down city planning has been massively destructive and concerning in history. Much of Hitler’s “Mein Kampf” is devoted to his plan to organize German cities differently, with certainly some similar ideas you can find in the 15-minute city plan. I was astonished this wasn’t mentioned in this episode, as it would be one of the obvious reasons behind why there is so much uproar. Some of these ideas were proposed and tried in the Soviet Union as well. In both historical cases, not all, but some of these ideas contributed to oppression and racism. The long and short, I think it is important to give a properly nuanced understanding and representation of the opposing side.

Also, painting figures like Joe Rogan and Jordan Peterson as extremist and “far-right” is simply inaccurate. I don’t agree with these figures, but they are certainly mainstream at this point, and their views are not all that unprecedented or far-fetched. It is this type of ostracism that I am afraid is so divisive in our society right now (when we paint anyone we disagree with as “far-right”. conspiracy theorist, or extremist). Again, I am not a Republican, definitely not far-right nor a conspiracy theorist, and I absolutely love your show. And, I actually like many parts of the idea of the 15-minute city. I just see the obvious concerns of it being a bureaucratic top-down approach, and would not describe someone holding those views as extreme. But episodes like this will only alienate good parts of your audience.

Just my two cents.

Important topic, but I’m shocked that an episode on walkable urbanism could be made without reference to the Congress for the New Urbanism or any of the countless traditional urban planners who have been creating walkable communities for decades.

I support the 15 Minute City concept, but I see why opponents have concerns, and I’m not sure that you addressed all of them. These are people who have lost faith in government (usually more because of government incompetence rather than deliberate bad actions) and who have spent a couple of years restricted in their movement and ability to travel. Many of them have also been subject to congestion charges or other restrictions on vehicle movements, and I suspect that many of them don’t have confidence that, if motor car trips to other parts of a city (or rural areas) become economically impossible, their local government will have the skills / desire / money to provide alternative means of transportation. And so their “district” will become self-contained, whether intended or not. Their government has only too recently exercised its power to restrict people’s movement, so why would they trust that government to further restrict vehicular movement, particularly when they have no faith that alternate transport systems will actually be built? Like it or not, congestion/traffic management initiatives have the capacity to completely inhibit other elements of the 15 Minute City concept.

As always this was a fascinating episode & I appreciate the viewpoints shared. However, I kept waiting for the topic to evolve & explore how the concept could address equity in urban planning. Why/how did you avoid this? How can the planning principles redress historic service denial such as food deserts (grocery stores) & health disparities (clinics & pharmacies)? How can transit be reoriented to serve neighborhoods/districts rather than a basic hub/spoke system? You spent more time disparaging daft nay-sayers rather than emphasizing improved quality of life from the approach.

No mention of plans to tax you, and your vehicle if you leave your 15 minute city.

I’m a listener from Shanghai, China. I would say, we have this mixed concept of zoning and 15-munite planning. On the one hand, the city has mixed area of residential, parks, supermarkets and more. On the other hand, the city certainly has working districts and other districts. In particular, I want to mention some chemical industries are better be grouped together.

Truely, no one version fits all, every city has its way.