Archaeologists searching through the ruins of the very ancient past are always happy to come across an epic poem or a historical chronicle, but very often the hardest documents to find are the ones that tell historians something about everyday life. About what it was like to be a bureaucrat in Egypt’s middle kingdom, or a soldier in the Persian Army, or a farmer in ancient Sumeria. It’s not that these societies didn’t produce lots of everyday communications. Frequently, they did. But it’s often the most common, ordinary documents that don’t survive. Either because no one thought to preserve them or their society was conquered, or they were written down on a medium that wasn’t meant to last. But in the 1840s archaeologists excavating the ancient city of Nineveh, in what is today northern Iraq, discovered an incredible stash of 2500 year old ephemera that did manage to survive.

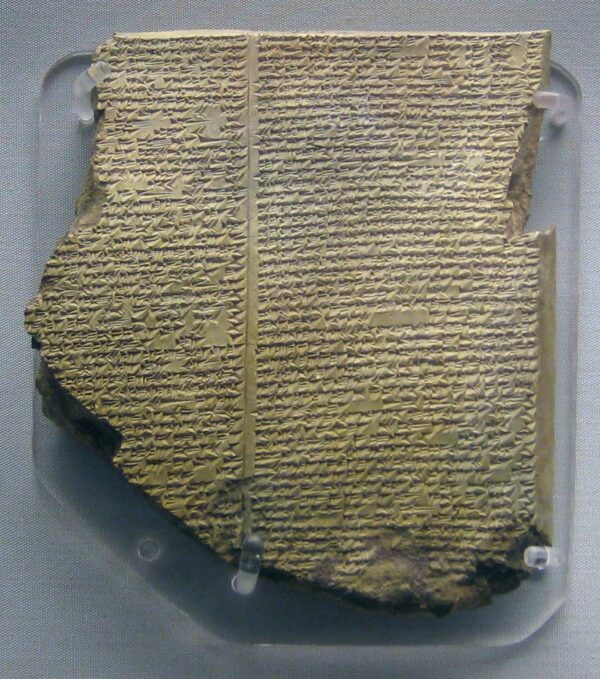

Nineveh had been the capital of the vast Neo-Assyrian Empire, which had reached the peak of its power in the 7th century BCE. Very little was known about the Neo-Assyrians, explains Lisa Wilhelmi, assistant professor of ancient near east studies at the Free University of Berlin, until the archaeologists at Nineveh came across tens of thousands of remarkably well preserved clay tablets. They had stumbled upon the Assyrian’s official state archive, built by the great Assyrian king Ashurbanipal. The Library of Ashurbanipal, as it came to be known, included ancient works of astronomy, mythology and literature, including the first discovered copy of the Epic of Gilgamesh. But it also included the daily personal correspondence of the Assyrian court – all of the petitions from ordinary people, all of the letters between advisors, and, critically, all of the messages being written to and from the Assyrian king. A glimpse, in other words, into the everyday life of the imperial court.

To the rest of the world, the Assyrians portrayed an image of nearly totalitarian power. David David Damrosch, professor of comparative literature at Harvard, and author of Around the World in 80 Books, says that image included infinite confidence and sagacity on the part of the king and the infinite loyalty on the part of the king’s ministers. But the personal correspondence of one king, named Esarhaddon, revealed a different story, because in private the all-powerful Esarhaddon was actually cripplingly neurotic.

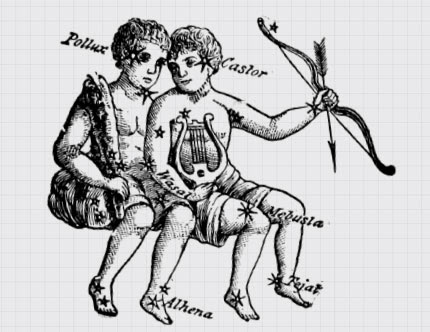

Nowhere was Essarhadon’s neurosis more clear than in his over-interpretation of omens. In one exchange, Esarhaddon was getting ready for an important military campaign, but one day, when he was exiting his great palace in Nineveh, a mongoose passed under his chariot. Essarhadon wrote to his chief priest asking what it could mean. He had heard it said that a mongoose passing under one’s legs was a bad omen, so perhaps they shouldn’t invade? Then again, technically the mongoose passed under his chariot, not his legs, so maybe all was well. What did the priest think? The priest wrote back:

As to what my lord the king wrote to me: “Does the omen ‘If something passes between the legs of a man’ apply to something that came out from underneath a chariot?”—it does apply.

However, he went on to say that Esarhaddon had it all backwards. And not to worry because this was actually a bad omen for his enemies.

[So should we say] “mercy” for the Nabataeans? Why? Are they not hostile kings? They will not submit beneath my lord the king’s chariot.

Essarhadon’s paranoia knew no bounds. In addition to over-interpreting omens, he commissioned multiple independent oracles and then cross-checked the results to see who – if anyone – might be betraying him:

Shamash, great lord, give me a definite answer to what I ask you! … Will any of the eunuchs or the bearded officials, the king’s entourage, or any of his brothers and uncles, or junior members of the royal line, or any relative of the king whatever, or the prefects, or the recruitment officers, or his personal guard, or the king’s chariot men, or the keepers of the inner gates, or the keepers of the outer gates, or the attendants and lackeys of the stables, or the cooks, confectioners, and bakers, the entire body of craftsmen … or their brothers, or their sons, or their nephews, or their friends, or their guests, or their accomplices … make an uprising and rebellion against Esarhaddon, king of Assyria … and kill him?

In fairness to Esarhaddon, a king would not be able to ignore omens and oracles even if he had wanted to. This was a society where divination literature was taken seriously by everyone and therefore was inherently political in its implications. Esarhaddon had also grown up as a boy in a time of deadly court politics – his own father had been killed by one of his brothers in a coup.

But perhaps Esarhaddon’s biggest problem is that he did not know how to read. Reading and writing in cuneiform was hard to learn and usually considered a speciality skill, much like coding is today. It was not expected for kings to learn, but this often put them at the mercy of their more literate scribes and advisors, who could choose not to recite crucial parts of a message. One tablet addressed to the king even included a postscript for the scribe begging him to read the entire letter aloud.

But Esarhaddon’s illiteracy is one of the things that has allowed us to know so much about the Assyrians today. Determined that future kings would not be stuck in his position, Esarhaddon likely is the one who ensured that his son, Ashurbanipal, learned to read and write from an early age. Ashurbanipal became a true lover of letters, even writing his own poetry. When he became king, he collected documents from around his empire, turning the archive in Nineveh into what we would think of as a proper library – one containing both great works of art and science, in addition to the palace’s existing records of daily correspondence.

Ashurbanipal’s library was burned to the ground and buried under rubble when the Neo-Assyrian’s vassal states rose up and destroyed Nineveh in 612 BCE. But in a further irony, the burning of the city might have been precisely what saved the library’s contents in the long run. When it comes to preserving the records of a society, sudden cataclysm is often better than slow deterioration, and in the case of the library, burning the tablets, far from destroying them, baked the tablets’ soft clay into something more like terracotta. The tablet’s new composition radically improved their durability, allowing them to be excavated largely intact 2500 years later – thereby ensuring that the lives of Esarhaddon and Ashurbanpial would be remembered forever – or at least until our own society’s inevitable decline.

Comments (1)

Share

Wow, do David Damrosch (whose audio is included in this episode) and David Gushee sound similar.