In the decades since the Holocaust, the phrase “never forget” has became a mantra for remembering this immensely tragic chapter of history. Like the longer saying that “those who forget history are doomed to repeat it,” it has become a call to action for people like German artist Gunter Demnig, whose decades-long awareness project is now considered the biggest decentralized memorial in the world.

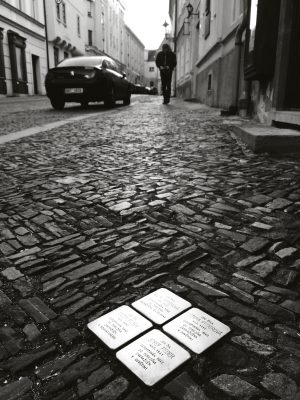

A single Stolperstein (translated: stumbling stone or stumbling block) is only small on its own, but since the early 1990s, Demnig has installed close to 100,000 Stolpersteine. Their design is deceptively simple: a plaque a few inches across with individual names, life dates and fates. But their messages are powerful — each one represents a victim of Nazi persecution or extermination. The markers are located at the last known place a given person being memorialized lived or worked as a tribute to their life until its point of tragic disruption. In explaining their purpose, Demnig cites a saying from the Talmud that “a person is only forgotten when his or her name is forgotten.”

The German word Stolperstein itself is both a layered allusion to a dark anti-Semitic saying but also a proverbial reference to encountering things by chance, as these plaques are meant to be. The power of these markers is not in their size or boldness, but in their pervasiveness. Major German cities have large Holocaust monuments and museums that speak to the scale and scope of this dark historical period, but these personal and unavoidable stones highlight individuals.

“I find it much more moving than these colossal or labyrinthine memorials,” one German said of the stones in an interview with The Guardian, “which to me feel quite bombastic and anonymous.” In contrast, “the Stolpersteine are so much more vivid and personal.”

What started with a few stones in a single German city dating back to 1992 has since become an international phenomenon. For Gunter Demnig, installing and maintaining these has become a full-time, year-round occupation spanning multiple countries and dozens of languages. The stones are not just expansive but also inclusive, covering no single targeted group but rather encompassing anyone who was persecuted. Still, the project is not without its detractors — some see it as disrespectful to place markers underfoot where they will be trod upon. But for their supporters, that is precisely the point — one can avoid a museum or overlook a monument, but there is no way around these everyday reminders embedded in city streets and sidewalks.

Comments (4)

Share

Thank you for this article! I lived in Bolzano, Italy, in 2018 and 2019. It was formerly part of Austria, was transferred to Italy after WWI, and was occupied by Germany near the end of WWII after Italy was taken by the Allies. The residents of the area were torn between Italian fascism and Nazi fascism.

Up in the hills around the city, there are ruins of Nazi anti-aircraft guns that fired at Allied bombers, which were trying to disrupt the industry in Bolzano as well as a key north–south train route.

Many people were sent from Bolzano to concentration camps and never returned; there are Stolpersteine around the city that subtly remind current residents of their history, which is delivered in strong doses in this part of the world.

Thank you so much for this article! I suggested the Stolpersteine as a possible mini-story episode a while back.

I have lived in Germany since 2006. One day I stumbled accross one of these stones in the pavement by my apartment. I was deeply affected. The person whose name and dates I just read lived where I was standing until one day the authorities came and took them a way.

Since then I stop and read every Stolperstein I come accross. It really makes the pervasiveness of the atrocities clear.

It also makes me proud of my adopted country. In the city where I live, every time a new Stolperstein is installed, school children come and witness the ceremony. They even write short biographies of the lives of the people commemorated with the help of the city archive. This is what truth and reconciliation looks like.

Always read the plaque and never forget!

We need these in the US to mark lynchings.

I’ve been reading stories from your fantastic book (The 99% Invisible City). I’ve just finished the story about sidewalk markings and immediately thought of Stolpersteine, after coming across them in Cologne a few years back. I was about to write and suggest them if you were to ever do a follow up episode and, well, I now realise you have it all covered.