Drive-in theaters have come a long way since the outdoor Theatre de Guadalupe in New Mexico first welcomed cars to join seated crowds at screenings in 1915. But decades of growth up through the 1950s and 60s gave way to decline in the 70s and 80s. A recent “guerrilla drive-in” movement, however, has begun to reinvent the concept, using new technologies to create mobile open-air theaters in the hearts of cities.

The Rise & Fall of Traditional Drive-Ins

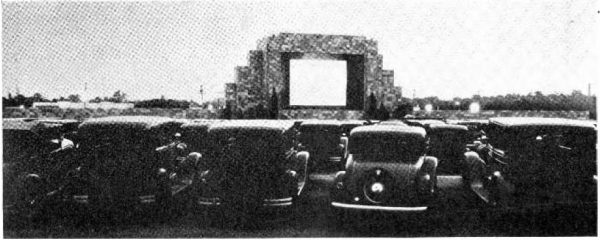

In the early 1930s, Richard M. Hollingshead Jr. of Camden, New Jersey began conducting tests in his home driveway to aid an unprecedented business venture. He set up speakers and put a Kodak projector on the hood of his car, aiming to figure out ideal viewing angles and volume levels before building and patenting the first drive-in-only theater. His facility opened with the slogan: “The whole family is welcome, regardless of how noisy the children are.” It ultimately failed to make a profit, but this prototype paved the way for a national trend.

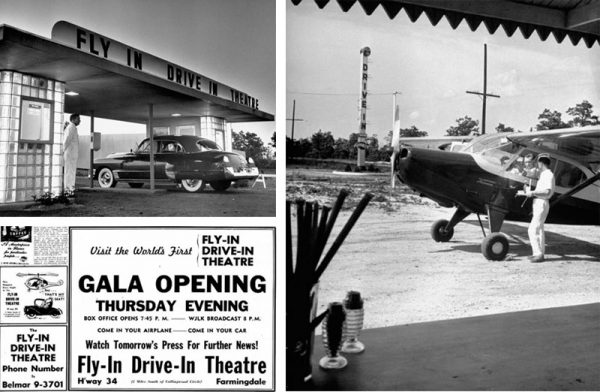

As the idea spread, a number of creative and sophisticated variants began to appear. In the 1940s, former navy pilot Edward Brown Jr opened the first Fly-In Drive-In theater with space for 25 airplanes. In the 1950s, the Johnny All-Weather Drive-In boasted the ability to host a record 2,500 vehicles on 28 acres, with a trolley system to cart people to and from on-site facilities including a restaurant and indoor theater.

Early drive-ins often had speakers located next to screens, which could make it difficult to hear films. This approach gave way to rows of speakers closer to the cars, then car-attached speakers and eventually radio-broadcast sound piped right into a vehicle’s audio system. But audio was only part of the problem: unpredictable weather, increasingly expensive real estate in close-to-city locations and the ability to show features only at night were all drags on profitability.

Some drive-ins today manage to persist in part because their operators have figured out ways to expand their function. The Fort Lauderdale Swap Shop, for instance, boasts being the one of the world’s largest drive-ins by night and a huge flea market by day.

The cost and complexity of converting to digital projection systems is also putting pressure on other remaining conventional drive-ins. At one point, there were over 4,000 drive-in theaters across the United states. Today, there are only a few hundred left.

Guerrilla Drive-Ins in the Age of Urbanization

Since the 1990s, a different type of outdoor movie theater has been gaining traction, in part thanks to evolving LCD projector and micro-radio transmitter technologies. These mobile guerrilla theaters take advantage of disused spaces and the inherently low-cost nature of utilizing non-permitted venues.

The Liberation Drive-In in Oakland, California, for instance, has projected programs on the sides of buildings and infrastructure in vacant lots and other underutilized downtown areas. Other examples in California include the Santa Cruz Guerilla Drive-In, North Bay Mobile Drive-In (in Novato), and MobMov (in San Francisco and Hollywood). Some of these organizations show popular contemporary movies while others feature experimental films.

The Liberation Drive-In in Oakland, California, for instance, has projected programs on the sides of buildings and infrastructure in vacant lots and other underutilized downtown areas. Other examples in California include the Santa Cruz Guerilla Drive-In, North Bay Mobile Drive-In (in Novato), and MobMov (in San Francisco and Hollywood). Some of these organizations show popular contemporary movies while others feature experimental films.

The quality, of course, is generally lower due to the equipment used and the surface projected on, but for MobMov focusing on that dimension misses the point. Their manifesto emphasizes social flexibility as an extension of the traditional drive-in experience: “Drive-ins were popular originally because it was like having your own private cineplex. If you wanted privacy, you’d just roll up your windows. If you wanted to be part of a community, you’d roll them down, open your doors, maybe even walk around.” MobMov takes a DIY attitude, encouraging anyone interested to join the movement. According to their website, they have over 20,000 members in 350 groups in cities around the globe.

The quality, of course, is generally lower due to the equipment used and the surface projected on, but for MobMov focusing on that dimension misses the point. Their manifesto emphasizes social flexibility as an extension of the traditional drive-in experience: “Drive-ins were popular originally because it was like having your own private cineplex. If you wanted privacy, you’d just roll up your windows. If you wanted to be part of a community, you’d roll them down, open your doors, maybe even walk around.” MobMov takes a DIY attitude, encouraging anyone interested to join the movement. According to their website, they have over 20,000 members in 350 groups in cities around the globe.

MobMov’s tagline is “the drive-in that drives in.” Unlike conventional drive-ins, these “theaters” themselves are mobile — cars equipped with vehicle-mounted projectors can simply pull into a lot and play a film. Audio broadcast by radio allows viewers to just drive up and tune in — this translates to lower costs while also creating less of a disturbance.

Some guerrilla drive-ins operate with property owner permissions or city-granted permits. But many fly under the radar, moving from place to place and using word-of-mouth, websites or mailing lists to spread showtimes and locations. Generally, the films are free to watch, but the approach has another key advantage for viewers: it brings drive-ins to urban areas, following the flow of audiences in this city-driven age.

Comments (4)

Share

When we started Santa Cruz Guerilla Drive-In, we noticed that there were few if any places for people to gather at night without spending money, just the usual bars, restaurants, and coffee shops. We wanted to challenge ideas around commodification and who was the public in public space.

For us, while we always tried to show great movies that challenged societal expectations and a collection of great subversive shorts, it was less about the films and more about building community.

You can create your own guerilla drive-in by checking out http://www.guerilladrivein.org/2005/04/start-your-own-guerilla-drive-in.html

As we put it back in back in 2001 when we started: You get the pleasures of participating in a gift economy, bringing together a broad community, providing a place to meet unmediated by commerce, and reclaiming public space!

Santa Cruz Guerilla Drive-In

If your ever in Idaho there are two amazing drive-in movie theaters, one with an awesome view of the Grand Tetons, aptly called “Teton Vu” in the background and another overlooking the Teton River valley also cleverly called “The Spud” google the Spud and see the novelty giant potato on a farm truck. Both play current movies and get quite the crowd in the summer.

MobMov’s tagline is “the drive-in the drives in.”

*that drives in.

Thanks – fixed!