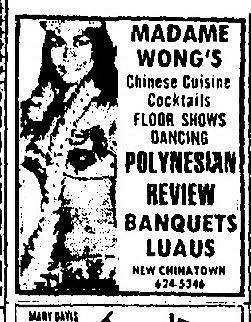

The most recognizable feature of LA’s Chinatown is its Central Plaza. It’s an outdoor pedestrian mall that is almost overwhelmingly colorful. Brightly painted buildings are topped with sweeping pagoda style roofs, and then accented with fluorescent neon lacing. For decades Central Plaza was a thriving tourist area, but by the late 1970s, Chinatown had fallen on hard times. The neighborhood’s neon lights still glowed over the shops and restaurants – but there was no one there to take it all in. Then, in 1978, the area captured the interest of Paul Greenstein, a music promoter and aspiring club owner — in particular: a restaurant named Madame Wong’s, overflowing with the sounds of music and people. Except it was empty. The sounds of party-goers were just that: sounds, recorded and replayed.

Like a lot of business in Chinatown, the restaurant wasn’t doing well. Madame Wong’s would be lucky to get a few dozen people in during the evenings. An enterprising promoter, Paul wanted to turn Madame Wong’s into a new, hot music venue: a venue that he would book and promote. At the time, there was a rising musical genre just screaming for a new venue: punk.

Like a lot of business in Chinatown, the restaurant wasn’t doing well. Madame Wong’s would be lucky to get a few dozen people in during the evenings. An enterprising promoter, Paul wanted to turn Madame Wong’s into a new, hot music venue: a venue that he would book and promote. At the time, there was a rising musical genre just screaming for a new venue: punk.

But the issue was that almost no one — not the biggest arena or the smallest clubs — wanted to host these local bands because they had a reputation for rowdiness and destruction. So punks had to make do. They’d try sliding in through the backdoor of alternative, unsuspecting venues. Some bands would book shows in abandoned synagogues, or Ukrainian cultural centers, or the performance hall of the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks. But as soon as the establishment figured out what was happening, they’d pull the plug or call the cops.

Paul Greenstein was not a punk, but was able to spot an opportunity when it was right in front of his face. Paul was seeing that day after day, night after night, Madame Wong’s was sitting empty, and that there were tons of bands who would kill to play their tiki-themed stage. So he asked George and Esther Wong, if they’d be willing to open up their doors to local bands. The Wongs weren’t exactly thrilled with the idea, but agreed to give him Tuesday nights for a trial run.

Paul Greenstein was not a punk, but was able to spot an opportunity when it was right in front of his face. Paul was seeing that day after day, night after night, Madame Wong’s was sitting empty, and that there were tons of bands who would kill to play their tiki-themed stage. So he asked George and Esther Wong, if they’d be willing to open up their doors to local bands. The Wongs weren’t exactly thrilled with the idea, but agreed to give him Tuesday nights for a trial run.

Aside from the cool vibe and a convenient location, there were intangible qualities that lured young punks to Madame Wong’s. : Chinatown was safer than a lot of the other punk hangouts in Los Angeles and a big part of the appeal for punks coming to Chinatown was the “edgy” aesthetic; and Chinatown seemed edgy, mainly, because it wasn’t rich, and it wasn’t white. “I would feel that what was going on in the punk scene is kind of similar to what happened in Chinatown for four decades beforehand,” says William Gow, assistant professor of ethnic studies at Sacramento State University. He says that Central Plaza was built in the 1930s for the local Chinese American community, but it was also built by Chinese American business leaders in a way to attract outside tourists to the area to spend money.

So in the late 1970s when Chinatown again had fallen on hard times, Esther And George Wong were using the same strategy again. Namely, catering to tourists. “If you have Chinese-American businesses who are trying to attract, whose lifeblood is are people outside of the community,” says Gow, “the punk scene is just going to be another kind of aspect of that.”

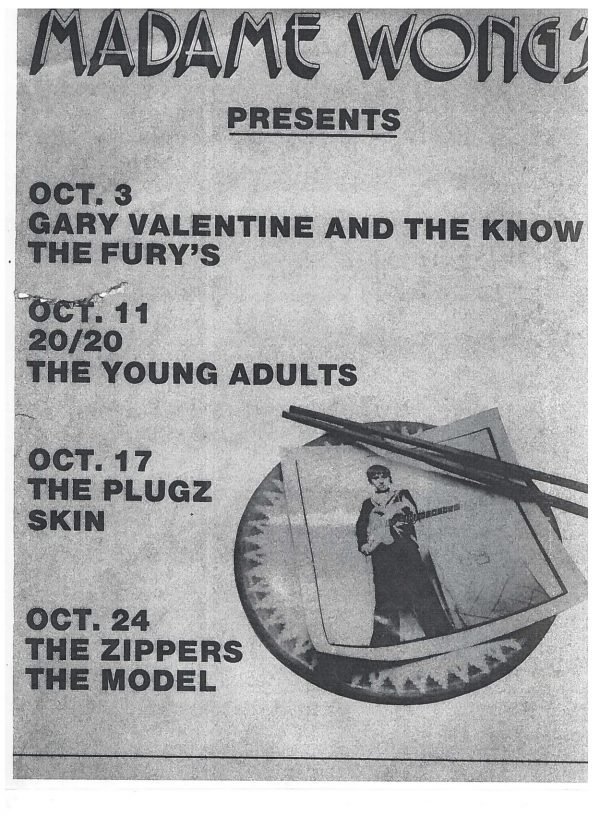

This sticky symbiosis between Paul and the Wongs was not without its tensions. Paul and Esther had different ideas for the club, so just a few months after Madam Wong’s became a punk haven, Paul was out and Esther was charting her club’s destiny. Within a year of opening Esther had turned Madame Wong’s into a prestige gig. They started booking not just local, unsigned LA acts, but big musicians from all over the world. It went from being a place that you played because there was nowhere else to go, to being the place that you had to play. Still, it wasn’t all smooth sailing. There’s actually a story that Esther pulled two members of the Ramones off the stage to make them clean up graffiti they had left on the bathroom walls.

But success spoke for itself, and Esther and George doubled down and opened up a second, even larger location in Santa Monica called Madame Wong’s West. The Wongs were savvy business owners who were strategic about how they ran their clubs. Since Madame Wong’s made most of its money through sales at the bar, George Wong would keep all sorts of detailed notes on the types of audiences that certain bands would bring in. Around the time that Esther discovered rock in the late 1970s, punk music was changing and a new style was splintering out into its own separate genre: new wave.

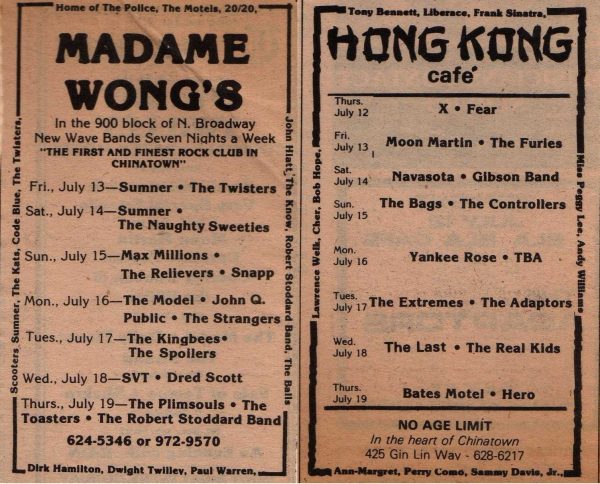

Although punk music put Madame Wong’s and Chinatown on the map, the crowds were rowdy and wrecked her beautiful restaurant. So as business began picking up, Esther pivoted and focused on booking new wave over punk. The new wavers tended to act a little more professionally and draw in slightly tamer audiences. Traditional punk fans were in the market for a new venue.

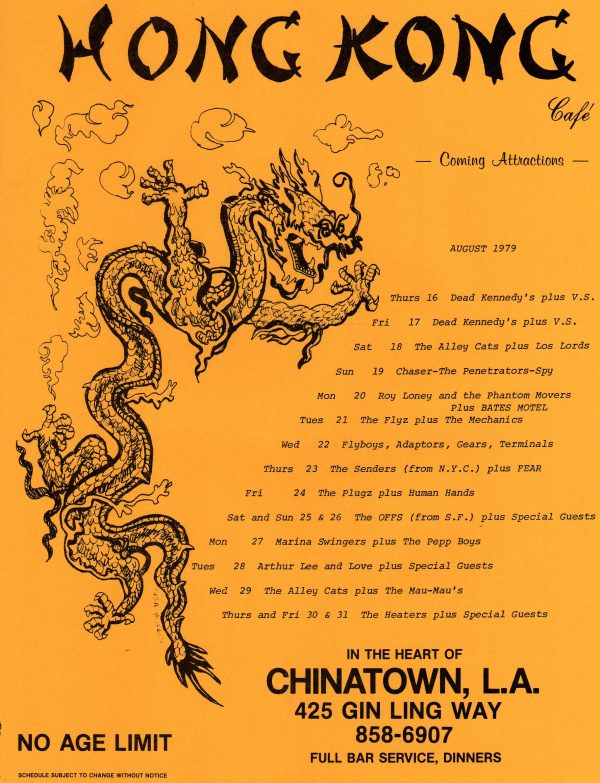

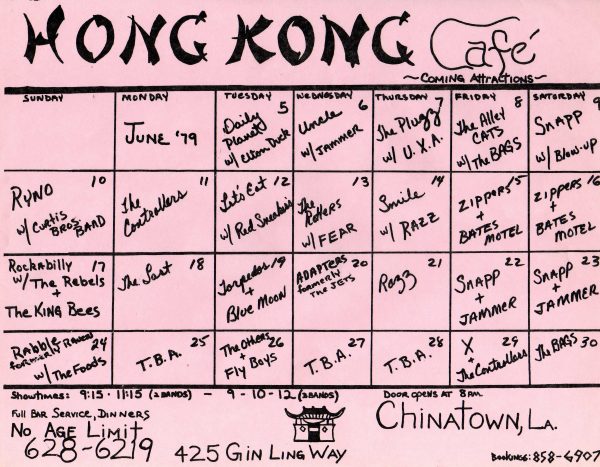

Hong Kong Low was a large, two-story building. On the ground floor was the main dining area, and on the second floor was a private banquet room that was booked out for buffets and special events. The banquet room was mostly unused, and represented a prime opportunity for someone with a vision.

Barry Seidel, like Esther Wong, did not originally set out to be a champion for punk music. But he had overheard the angry grumblings of punk bands who had been booted out of Madame Wong’s and they saw an opportunity for a business model. Every choice that Madame Wong’s made, the guys at the Hong Kong purposefully went the other direction. Esther made Madame Wong’s 21 and up, so the Hong Kong was all ages. If Madame Wong’s was going to cast out the unruly punk bands, the Hong Kong would would take them in.

The shows took a toll on the Hong Kong Cafe but the owners and organizers eventually worked out a deal that any damage done to the club would be taken out of the band’s cut of the night. The shows and audiences could get chaotic, but it was all worth it to draw bigger crowds into Central Plaza. Bigger crowds meant more money spent at the bar and in the restaurant. And although it was mainly a business decision for owner Bill Hong, the Hong Kong Cafe ended up becoming hugely important to the punk scene. The blood-soaked shows were working — kids who had to be turned away at the door were scaling the roof and breaking in through the air conditioning ducts.

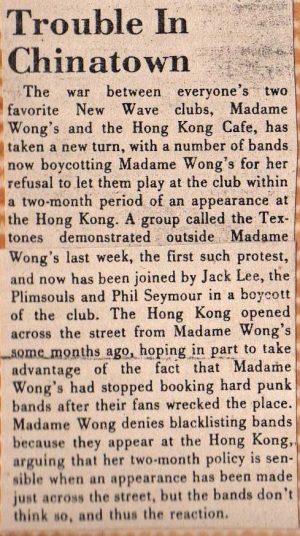

One person who was not a fan of the Hong Kong’s chaotic, punk-loving vibe was Esther Wong. In the beginning, Esther was actually quoted in the LA Times welcoming the competition in Chinatown, but that attitude changed very quickly. Tensions grew. On one side of the courtyard was Esther Wong and her skinny-tie-wearing new wave bands, and on the other was the Hong Kong and the punks. The LA press got wind of this tension in Chinatown and stoked the flames of the feud. The local media gave the whole clash a nickname that was probably intended to be snappy, but exposed the underlying racism lurking below the surface: the Wonton Wars.

Punk music in Chinatown burned bright, but it burned fast. Within a few years, the genre had evolved and by 1981 bands like the Bags, The Alley Cats, and the Dils who helped define the sound of first wave LA punk had drifted out of the scene. Punk wasn’t dying, but it *was* changing. The music was being overtaken by hardcore bands and audiences. It was faster, harder, more aggressive, and tended to bring in a very different crowd. Madame Wong’s managed to survive punk and the introduction of MTV in the early 80s, but the bottom line is that even if you were successful, there wasn’t a lot of money in running rock clubs. After a while, the hassle just wasn’t worth it anymore.

Punk music in Chinatown burned bright, but it burned fast. Within a few years, the genre had evolved and by 1981 bands like the Bags, The Alley Cats, and the Dils who helped define the sound of first wave LA punk had drifted out of the scene. Punk wasn’t dying, but it *was* changing. The music was being overtaken by hardcore bands and audiences. It was faster, harder, more aggressive, and tended to bring in a very different crowd. Madame Wong’s managed to survive punk and the introduction of MTV in the early 80s, but the bottom line is that even if you were successful, there wasn’t a lot of money in running rock clubs. After a while, the hassle just wasn’t worth it anymore.

The improbable alliance that Esther formed with her rock-seeking customers in Chinatown had come apart. In 1986 she told the LA Times, “The kids that come here now, they drive me crazy. They come here and act like spoiled brats. Some of them plugged up my toilets, and one band set fire to some paper towels and set off our sprinkler system, flooding the whole basement… It’s got me pretty discouraged.” After that fire in 1986, Esther announced she was closing Madame Wong’s East in Chinatown. And in 1991, after featuring bands like Oingo Boingo, REM, and the Red Hot Chili Peppers… Madame Wong’s West closed its doors as well. By this time, Esther was well into her 70s and the music landscape was a completely different place.

Esther Wong died from emphysema in 2005 at the age of 88. Even though her legacy was disputed by many over the years, the LA Times eulogized her as “The Godmother of Punk.” Chinatown is the kind of neighborhood that changes so quickly that if you blink, it could look like a completely different place. Punk ended up just being a phase that like so many people.. Chinatown eventually grew out of.

Esther Wong died from emphysema in 2005 at the age of 88. Even though her legacy was disputed by many over the years, the LA Times eulogized her as “The Godmother of Punk.” Chinatown is the kind of neighborhood that changes so quickly that if you blink, it could look like a completely different place. Punk ended up just being a phase that like so many people.. Chinatown eventually grew out of.

Correction: We originally reported that Barry Seidel left the music industry after working at the Hong Kong Cafe but he continued managing and producing music afterward.

Comments (3)

Share

This episode is reported and told amazingly – Vivian, I don’t have a favorite on staff, but if I did, it might be you.

But as with so many true-to-the-soul things in 99PI pieces, the ending attributions/outros have been one of my favorite extras since you all took up residence with SiriusXM and Stitcher. And this episode’s outro was PERFECTION. I don’t know whose idea it was, but kudos x1000, it made me laugh and yawp out loud, and it is (to me) representative of what’s at the heart of your collective personalities, and an indicator that you are all people I would want to hang out with if I knew you IRL.

I love your show – Roman, bless you for seeing things through all these years.

What’s the closing credit song on here? Great episode, but that song sounds unreal. 46:50 is the time stamp. The tune at 48:40 as well? What do we have?

Thanks!

Thanks for giving proper credit to the people who actually got that scene started. The other articles I’ve read about the Chinatown make it sound as though Esther Wong discovered punk rock herself.