For Black Atlantans, Collier Heights became a suburban jewel in the postwar South spanning thousands of acres and packed with nature. Just as amazing as the expansive beauty is how this neighborhood came to be, especially given everything that stood in the way. Collier Heights was established in the early 1950s, when redlining and racial zoning all put hard limits on where Black people could live. Driving its development was a team of community leaders who used cold, sharp strategy, flipping the logic of Jim Crow housing segregation on its head.

It started in Atlanta, which is “a special city for Black folk” says Maurice Hobson, author of The Legend of The Black Mecca – Politics and Class in the Making of Modern Atlanta. “I do not make any if ands or buts about it. I love this city.” And certainly, by the end of WWII, that was a well-known moniker for the city, which drew Black people from around the country. For close to a century, Black Atlantans had been building successful businesses, earning higher education degrees, and accumulating wealth and political power at levels few other cities could compete with, especially in the South.

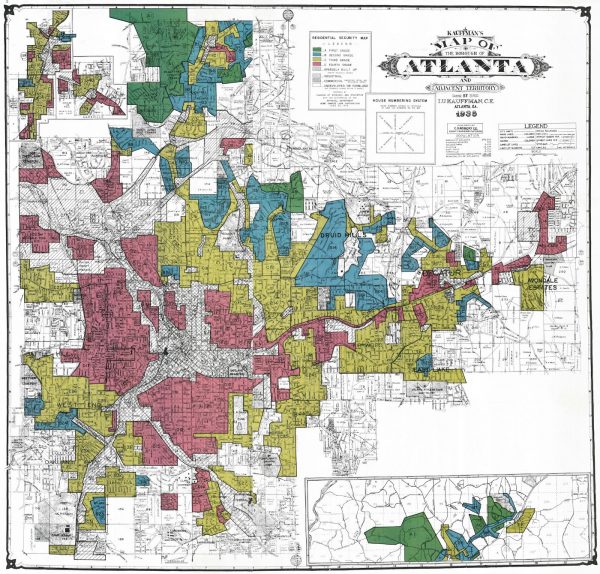

But this was still the Deep South, and Atlanta was deeply segregated, especially when it came to housing. In the mid 1940s, that system helped fuel a major housing crisis in the city. Atlanta’s population was spiking with wartime migrant labor, and soldiers coming back home.

For decades, most of Atlanta’s Black communities had been strictly segregated and confined to certain parts of the city. Even the Black people with money had to squeeze into just a few segregated neighborhoods, with a limited number of houses and apartment. Often, too, these were situated in unappealing places — in the midst of flood zones, adjacent to smog-producing industry, and so on, all because the city had zoned districts by race.

Compounding the housing shortage crisis, the federal government wouldn’t guarantee loans to Black families, insisting that they’d cause property values in white neighborhoods to tank. On the rare occasion Black homebuyers did break through, things could get ugly. In the late 40s, a Black beautician had her house in a white community west of downtown dynamited just after buying it — probably by an offshoot of the Ku Klux Klan. Into this world of entrenched housing segregation and terrorism against Black homebuyers stepped an activist named Robert Thompson, who helped find an end run around the whole system.

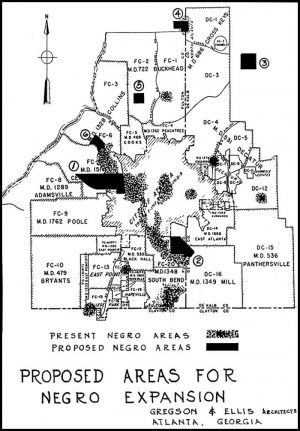

Thompson was the Atlanta Urban League housing secretary. He believed that housing could be used as a tool for racial progress. In the 1940s, he helped lead an effort to plot out a lot more living spaces for Black Atlantans. He and a group of prominent Black Atlantans identified half a dozen so-called “Negro Expansion Areas.” These were small pockets spread around Atlanta that were very carefully plotted out in order to protect future Black residents from violent white backlash.

Thompson was the Atlanta Urban League housing secretary. He believed that housing could be used as a tool for racial progress. In the 1940s, he helped lead an effort to plot out a lot more living spaces for Black Atlantans. He and a group of prominent Black Atlantans identified half a dozen so-called “Negro Expansion Areas.” These were small pockets spread around Atlanta that were very carefully plotted out in order to protect future Black residents from violent white backlash.

The group met with white neighborhood associations, and they struck so-called “gentlemen’s agreements” to use highways, cemeteries, train tracks and other landmarks as boundaries between the Black “expansion areas” and white neighborhoods. But these few small areas weren’t enough for a growing Black Atlanta. Plus, some of the city’s Black leadership disliked these “gentlemen’s agreements,” just on principle, viewing informal bounders as endorsements of segregation.

So while the expansion areas went ahead, Thompson and his team decided around 1950 that it was time for a much bigger, bolder play — one that would harness Black Atlanta’s development know-how, and its wealth. They called the plan Project X. Thompson’s team started by surveying land west of central Atlanta. There were some white neighborhoods out there, and a few small Black communities. But to the west of all those, they saw a lot of undeveloped land that stretched all the way out to the county line. Their mission: find ways to buy up that land, and develop it. Since those parcels were outside the city limits, they weren’t subject to Atlanta’s race-based zoning laws. So Black people could still buy it, if the owners were willing to sell.

Thompson’s team came up with a plan to use racism in the real estate market to their advantage. The Project X team knew that because they were Black, they could depress the value of white-owned space by simply buying property that was adjacent. The white owner would then likely be pressured to sell. And once white communities found out there were Black people next door, those residents were likely to move, and white homebuyers would shop elsewhere. Either way, all of that space would then be open to Black Atlanta. Manipulating Jim Crow psychology was just a tactic on the way to creating great Black neighborhoods. Project X counted on the fear of a Black neighbor.

But they had to keep Project X kind of on the low. White communities were expanding, too. If they sensed that Black developers wanted this land, they might snatch it up first, effectively cutting off the west side to Black people. So one of their first big steps was to assemble a group of 23 investors, including a few doctors, some teachers, a newspaper editor, and a housewife. They formed a corporation, sold shares to raise money, and set their sights on more than a thousand acres. They went deep into the west side, and just started buying up land next to white communities, which were caught completely unawares.

Where the old plan for expansion areas had Black neighborhoods surrounded by white homes, Project X flipped that. Black developers were now encircling white communities. In neighborhoods around west Atlanta, locals started seeing these modern, gleaming new middle-class houses go up on what used to be farmland or woods. White homeowners then watched in amazement as Black families moved in. Within a few years, multiple white neighborhoods found themselves encircled. Robert Thompson described the strategy as both a leapfrog, and a military style pincer move. This Project X strategy helped open up Atlanta’s west side for Black development.

One of the places where these tactics were used to best effect was a stretch of lush, hilly land just west of Hightower Road — a country lane that marked the edge of a small white suburb. It had plenty of vacant land. In 1953, a Black development company used the leapfrog tactics to buy a thousand acres west of that white neighborhood. The small existing white community tried to form a united front when Black people started moving in next door. The civic club made it a moral issue, pressuring neighbors to stay loyal to the white race by holding the line. Those who wanted to sell were accused of being selfish. But within just a few months, every white resident had sold their house to a Black buyer. It was all over. White Collier Heights became a Black community.

In the mid 1950s, this neighborhood became Atlanta’s finest development for Black people, where houses went for 20 to 50 thousand dollars.

By the mid 1960s, Collier Heights was the dream — a modern, 4,000 acre oasis. Black suburbanization was happening fast, especially across the South. But in terms of its sheer scale, its newness, and its status as a middle and upper middle class neighborhood, there was nothing else like Collier Heights anywhere in the country.

Collier Heights grew to encompass 54 subdivisions — places like King’s Grant, Miami Heights, Crescendo Valley. Black Atlantans who drove out looking for their dream homes would park and take footpaths up through vast front lawns. They’d tour split level homes that sometimes went multiple stories down the back of a hill.

Various recent home sale listings in Collier Heights via Zillow and Trulia, including a home with a pagoda-style roof (lower right)

The area had a whole rainbow of ranch styles: compact, linear, linear with clusters, bungalow, alphabet. Some of them designed by the best architects in the game. There were homes with pagoda-inspired roofs, and others designed in a style called “The Woodland Master Deluxe Split-Level.” There was one house – it’s still there – built in the round for perfect acoustics, custom made for the local high school band director.

In an Ebony magazine feature from 1971 titled “Atlanta – Black Mecca of the South,” Collier Heights was described as one of just a few “verdant neighborhoods that are the true pride and joy of the city’s Black citizenry.” The neighborhood had also become a who’s who of successful Black Atlanta. Rev. Martin Luther King, Senior had a house there, as did civil rights leader Ralph Abernathy.

But not everyone in Collier Heights was famous, or part of the wealthy elite. Some were HBCU professors, laborers, clerks, and librarians. Some were strivers who’d scraped together just enough to buy themselves and their families some of the good life out there. By the early 1970s, the community had grown to include two thousand homes built from scratch. Even tourists came to see Collier Heights. For the people who lived there, the neighborhood had become more than just a solution to a housing crisis in a segregated city. Black folks wanted in on the suburban dream, and Collier Heights had promised to make it come true ten fold. Along with peace and fresh air, this cloistered all-Black suburb offered even a small break from white racism.

At the same time, Collier Heights was also a space where some upwardly mobile Black people could distinguish their community from lower income neighborhoods. And in general, Black Atlanta was proud that a space so grand had been made for and by Black people.

The neighborhood was also celebrated for showing the world a vision of Black progress: proof that Black people wanted to and could live well, even luxuriously, in suburbia. For its residents, Collier Heights represented the epitome of self-determination and dignity in a world of entrenched anti-blackness — a world where white Atlantans worked very hard to exclude them from certain communities. For a while, everything was new, built by and for Black people.

In 2009, Collier Heights was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The community was officially not new anymore. It’s also a lot smaller than it used to be. The neighborhood boundaries were redrawn, shrinking Collier Heights down to a historic core that’s less than a quarter of its original size. There’ve been other changes, too.

In 2009, Collier Heights was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The community was officially not new anymore. It’s also a lot smaller than it used to be. The neighborhood boundaries were redrawn, shrinking Collier Heights down to a historic core that’s less than a quarter of its original size. There’ve been other changes, too.

In recent decades, some residents have put ornate, wrought iron bars on their windows and doors for safety. Lawns have gotten a bit shaggy. Some of the houses could stand a little more care. The area’s greatest resource — that first generation of homeowners — is passing away. Sometimes the younger generations can’t or don’t really want to take care of the house. Which can lead to neglect. Many of those kids have their own homes, and they’re not interested in living in Collier Heights.

But in a sense, the plan behind the development worked — the older generation wanted their children to succeed and have choices, including the choice to move away from their hometown. Meanwhile, more and more people are looking to move to Collier Heights, drawn in part by its powerful origin story.

Comments (3)

Share

Here is a link to a more detailed version of the residential security map.

https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/#loc=13/33.793/-84.427&city=atlanta-ga

It is an old Atlanta story that Boulevard turns into Monroe Drive, because one was black and the other white. This map has information on this. In the rsm, Boulevard is seen as Boulevard north of Ponce De Leon Av., where the current street name change is. Furthermore, Boulevard goes through a C-yellow neighborhood on both sides of Ponce De Leon. The neighborhood does not turn into D-red until Wabash, a few blocks south of Ponce De Leon. Here is a story about the Monroe/Boulevard situation.

https://chamblee54.wordpress.com/2020/07/09/monroe-drive-or-boulevard-5/

Great piece! However, some of the houses pictured in the “[v]arious recent home sale listings…” section are in Collier Hills, not Collier Heights.

Why does this remind me of the game of ‘Go’?