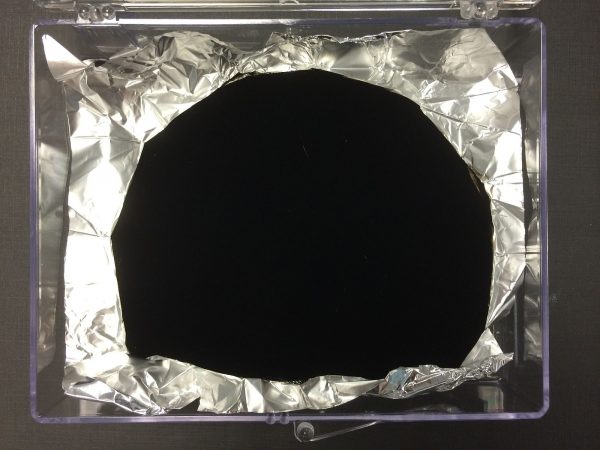

Vantablack is a pigment that reaches a level of darkness that’s so intense, it’s kind of upsetting. It’s so black it’s like looking at a hole cut out of the universe. “Vantablack is striking when you look at it… because it [doesn’t look] like something is colored black. It looks like an absence. It disappears,” explains Adam Rogers, a journalist who writes for Wired. Vantablack swallows nearly all visible light and gives back no reflection, so every contour or crease of whatever it’s applied to disappears. It has this odd effect of making something look two dimensional, while at the same time as if you can fall right through it.

If it looks unreal, it’s because Vantablack isn’t actually a color, it’s a form of nanotechnology. It was created by the tech industry for the tech industry, but this strange dark material would also go on to turn the art world on its head.

Blacker than Black

There are black pigments out there, and then there are SUPER-black pigments that are so dark, they need to be created in a laboratory. These super-blacks reach such extreme levels of darkness because they’re made up of something called carbon nanotubes, or CNTs. Carbon nanotubes are pretty much exactly what they sound like: tiny microscopic tubes comprised of black carbon atoms just a few nanometers in diameter. For reference, a single human hair is about 80-100 thousand nanometers wide. CNT materials are made up of forests of these microscopic black carbon tubes.

As Ben Jensen, founder and CTO of Surrey Nanosystems explains, “It’s like a field of grass. Okay. And the grass is a carbon nanotube and about 1/ 6000th the thickness of your hair and there’s about a billion of them per square centimeter. And they’re the equivalent of about 3,000 feet tall.” Jensen began working in the nanomaterials field in 2004. Back then, super-black pigments had a lot of promise in the space industry, but the technology wasn’t quite where it needed to be yet. Carbon nanotube coatings could be really useful inside of satellites, telescopes, and optical imaging technology because they could absorb stray light that affected calibration, but CNTs weren’t like a paint that you applied onto something—they had to be literally grown onto a surface, in a special type of reactor at 700 degrees centigrade—which is so hot that it would damage most material. This extreme heat really limited what type of material, known as the substrate, that carbon nanotubes could be grown on.

Surrey Nanosystems worked on it for years, and finally managed to develop a new reactor that allowed them to grow CNTs at a much lower temperature, and in doing so they accidentally created the darkest material in the world—one that trapped 99.965% of light. “We weren’t looking to create the world’s blackest material. That wasn’t our thing. We were trying to solve a calibration problem for space instruments using carbon nanotubes,” recalls Jensen. Surrey Nanosystems decided to give this new flashy CNT a flashy name: “Vantablack,” which stands for Vertically Aligned Nano Tube Array… Black.

Art of Darkness

Surrey Nanosystems launched Vantablack at the Farnborough Airshow in 2014. They were presenting their nanomaterial next to the Boeing Dreamliner, military jets, and a paragliding car so Jensen wasn’t expecting to make much of a splash. But once word got out about Vantablack, everyone wanted to know more about it. People were amazed by the depth of darkness achieved by Vantablack and wanted to know more. Soon enough Surrey Nanosystems was receiving all sorts of requests from people who wanted a piece of it. There were people getting in touch with them asking to coat their cars and bodies with Vantablack, Jensen even recalls having a YouTuber ask if he could eat it live on YouTube.

What really caught his attention Jensen was the amount of interest that came from another field in desperate need of a super-black pigment: the art world. In that first couple of weeks alone, Surrey Nanosystems received over 400 inquiries from artists wanting to use it in their work. Working with artists was just not something Surrey Nanosystems was equipped to do because Vantablack was incredibly hard to work with. Carbon nanotubes had to be grown at about 430 degrees centigrade, which is still hot enough to damage most materials. CNTs were also very delicate and could scrape off easily but most importantly, any collaboration with artists would take up time and tech resources since anything coated with Vantablack would have to be grown in Surrey Nanosystem’s reactors. Working with artists just didn’t seem like a practical move for the company… until they met Anish Kapoor.

His Dark Material

Anish Kapoor is an incredibly well-respected artist known for his conceptual art and large-scale art installations. He is probably best known for creating Chicago’s iconic Cloud Gate sculpture, and he was even knighted by Queen Elizabeth II for his contributions to visual arts. When Vantablack debuted, Kapoor reached out to Surrey Nanosystems and invited Jensen to check out his studio. “I walked into his studio and I was literally speechless at what I saw,” remembers Jensen.

Given his body of work, Kapoor seemed uniquely suited for this material. Kapoor has a fascination with black’s capacity to make something both exist and not exist at the same time. “His work—a lot of it—deals with color blocks and voids. [He] tries to understand the relationship between color and space—especially color, as the thing that fills a space and an absence of color is an empty space,” explains Rogers.

Surrey Nanosystems couldn’t work with 400 different artists, but they could work with one. Kapoor was a perfect choice. They signed a contract with Kapoor stating he would be the first and only artist who would get to work with Vantablack. Surrey Nanosystems already had all sorts of exclusive licenses with contractors in the defense and space industries, so they figured an artistic license wouldn’t be that different—but in reality… people didn’t see it that way.

At first, people thought that somehow Anish Kapoor had an exclusive license to the color black, which was completely false. “That created a firestorm of hatred. And I think back to that time, we were getting hate mail, death threats, all kinds of crazy stuff. You know, with the Internet is like,” remembers Jensen. Vantablack is a type of nanotechnology that can only be achieved using Surrey Nanosystems’ proprietary reactor and trained technicians. It is not a color. They didn’t patent a shade of black that absorbs 99.965% of light, they patented a unique process and material that absorbed 99.965% of light. Still, a lot of people didn’t understand that nuance.

Sharing is Caring

One person who understood the technical nuance of Vantablack, but still objected to this arrangement was an artist named Stuart Semple. “That didn’t change how I felt about this exclusive arrangement that had hatched,” says Semple. Semple doesn’t actually blame Surrey Nanosystems for choosing to work with Anish Kapoor. They came from the world of tech and had a completely different mindset. The object of his frustration has been Anish Kapoor. Morally, as an artist, Semple believes Kapoor should have known better than to try to keep Vantablack exclusively for himself. Historically, so much of art has been dependent on new technology, so the fact that a new material was purposefully being withheld from the rest of the artistic community ruffled a lot of feathers.

Ben Jensen is quick to point out that artists being protective of technology isn’t actually a new thing in the art world. Artists have been creating their own oil paints since the Renaissance and they were under no obligation to share their material with competitors.

Jensen explains, “People feel if something exists, they have an automatic right to it… The reality is the world has never been like that. You go back to when Turner was creating his blacks and you go up to him, say, ‘Hey, you created an amazing black. I want it.’ You would have been laughed out of the art scene.” Stuart Semple sees it in a different way. He believes that sharing knowledge and technology can only move the arts community forward. It was a clear cut disagreement on how the world operated vs. how one thought the world should operate.

Up Yours #Pink

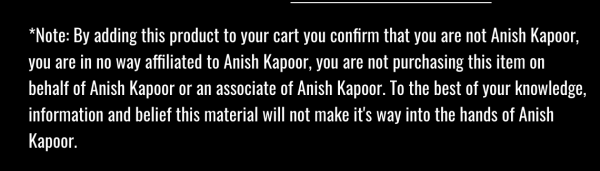

Semple had a bunch of pigments that he created himself: the Greenest Green, the Pinkest Pink, the Glitteriest Glitter—and he had an idea of how he could use his own colors to poke a little fun at Kapoor’s exclusivity arrangement. “So I thought, what I’ll do is I’ll share my Pinkest Pink that I made with the whole world and put it on the Internet as a joke, as a piece of performance art… And I would ban Anish Kapoor from using my pink.” It would be available to everyone except Anish Kapoor.

In order to buy Semple’s pink you have to agree to legal terms and conditions on the website when you add it to your cart that you are that you’re not Anish Kapoor, you’re in no way associated or affiliated to Anish Kapoor, and the best of your knowledge, information, and belief, the paint won’t make its hands into the way of Anish Kapoor. The move was part joke, part performance art. Semple ended up selling tens of thousands of jars of the Pinkest Pink. It was so popular that it even caught the attention of Anish Kapoor himself, which is where things began to escalate. Kapoor had managed to get a hold of the Pinkest Pink, and posted a picture to his Instagram account of his middle finger dipped in the pigment with the caption: “Up yours #pink.”

Paint it, Black

Semple says that he was really upset that Kapoor had gotten a hold of his color, but in a way, it was also really good for him. Semple had gotten one of the most prominent artists in the industry to publicly flip him the bird, and now he had the internet on his side. Commenters piled onto Anish Kapoor’s Instagram post telling him to #ShareTheBlack. Stuart suddenly found himself an army of art defenders behind him, and he was ready to mount a full-scale attack. He was going to try to make a better black—one that could rival Vantablack.

It took years of development, multiple iterations, and an entire community of crowdsourced artist feedback to develop the formula for something he calls Black 3.0. It’s an acrylic paint that relies on mattifiers from the cosmetics industry to create a very matte finish as well as a very deep black pigment. Black 3.0 doesn’t trap as much light as Vantablack—but it’s still very dark, easy to work with, and affordable for artists. Also, much like the Pinkest Pink, you can’t buy Black 3.0 if you’re Anish Kapoor, if you’re associated with Anish Kapoor, or to the best of your knowledge, information, and belief, it’s going to make its way into the hands of Anish Kapoor.

Anish Kapoor wouldn’t be using Black 3.0 anytime soon, but as it turns out… neither would Semple. “You know, it’s too black for my work. I can’t use it. It’s too black. The minute you put it on a painting, it just dominates everything,” explains Semple. He more so created it for the art community than for his own work. Oddly enough, Anish Kapoor, the person who set off this whole controversy in the first place hasn’t used his blackest black very much either aside from an exhibit at Beppu Park and limited edition $98,000 Vantablack watch.

Redemption of Vanity

Diemut Strebe is an artist who works at the intersection of science and art, and recently, she and scientists at MIT (at Brian Wardle‘s lab) came out of nowhere with a new growth method that rendered the entire feud between Kapoor and Semple pretty much meaningless. And the best part is, she didn’t even mean to. “My artwork really triggered a scientific discovery, which is unusual in these times… usually, artist work would not trigger a scientific paper, but in this case, it really came out of the arts,” says Strebe.

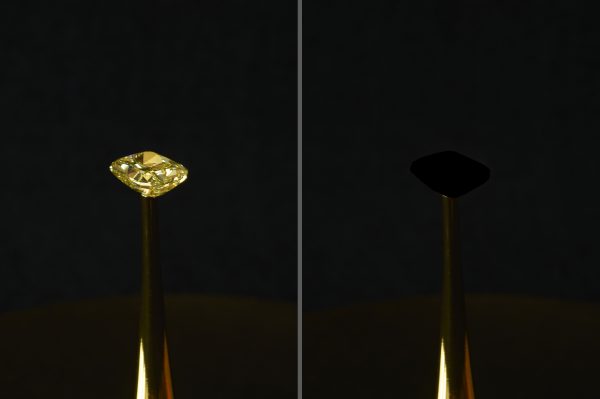

In 2019, Strebe released a work called The Redemption of Vanity in which she coated a two million dollar diamond with a new nanotube material developed by MIT’s Necstlab. The artwork can be seen as a critique of how we attach material and immaterial value to concepts and things in society, luxury, and the arts. The literal devaluation of an object of highly symbolic and economic value can be understood with respect to the embracing forces of art market mechanisms on the one hand while expressing at the same time questions of the value of art in a broader sense.

“Diamond and carbon nanotubes are two different arrangements of the same carbon atoms in a different order on a lattice structure,” explains Strebe, “And that really struck me because that means that you have the brightest material and the blackest material, basically generated from the same element.” One can consider the artwork as a reference to the Greek philosopher Heraclitus, who was obsessed with the idea of the united opposites. The Redemption of Vanity can be seen as the unification of the most extreme opposites in exposure to light, unified in the art piece.

This new carbon nanotube material coating the diamond is so dark that it actually unseated Vantablack as the new blackest material in the world. It traps an astronomical 99.995% of light as compared to Vantablack’s 99.965%, which seems like a subtle difference, but is actually 10x darker than anything previously reported.

Strebe worked on the project since 2014 and won a Residency at MIT in 2017 which targeted the CNT growth with Brian Wardle ‘s Necstlab for two of her art projects of which one is The Redemption of Vanity. Strebe’s main focus was her artistic idea and was never interested in the drama between Kapoor and Semple (although she was aware of it). She addressed the topic by proposing to her MIT colleagues to bypass Kapoor’s license, and when she succeeded, freed the blackest black from exclusiveness.

Fade to Black

Anish Kapoor still has the exclusive rights to use Vantablack in his artwork, and it’s unclear whether he’s planning on releasing any future pieces using the material. Actually, his most recent exhibition couldn’t be any further away from black. It’s a series of mirrored sculptures that are almost impossibly reflective. These days, Stuart Semple has a new giant to slay. He’s taken on T-Mobile. The company has been sending cease and desists to small businesses using a similar shade to their trademark pink, so in protest, he’s released a new pigment that he calls Pink™. It’s an exact color match to T-Mobile’s, and it’s available to anyone unless they are in any way affiliated with T-Mobile.

Ben Jensen is still at Surrey Nanosystems, developing newer iterations of Vantablack that are not exclusive to any artist. The material has come a long way since the Kapoor vs. Semple controversy, and iterations have been used to coat an entire building at the PyeongChang Winter Olympics, a BMW X6, and the company is even toying with the idea of coating movie theater walls with it to create an immersive film-going experience. Jensen seemed a little hesitant to dip his feet back into the art world though.

As for the black that came out of MIT, although there is little wiggle room for improvement left, Diemut Strebe knows this isn’t going to be the end-all-be-all for the world’s darkest pigment. Another material will eventually come along and end their reign as the blackest black. But what’s a beautiful side effect to Strebe and Necstlab’s material isn’t that it’s the darkest, but that it’s available to the rest of the art world. Strebe is more interested in the artistic concepts and the avant-garde role the art/science interface can play than contributing to discussions she views as having no artistic value. She, of course, is happy the blackest back is freed from exclusiveness. So for now, the blackest black is open to any artist to use, including Anish Kapoor.

Correction: This episode did not originally include Anish Kapoor’s installations at Beppu Park in Japan. This article has been updated to include it.

Comments (7)

Share

Surrey NanoSystems recently made this art piece for the Europa Clipper mission science team! It’s a black monolith just like the one in 2001: A Space Odyssey! Link below for anyone interested, not a ton of info about it outside of twitter.

https://twitter.com/surreynanosys/status/1112703491137515521

Such a faciniating episode, thank you! Does anyone know the process that was used to apply the MIT nanotube material to the diamond?

They should use this for the US Space Force uniforms. heh heh

#sharetheblack

You could say Vanta Black is 99% invisible.

Yet another competing super-black coating appeared on Kickstarter a few months back, product name Singularity 2. Got funded, product shipping now supposedly. Not sure what, if any, involvement they have with the cast of characters in this story.

You should check out nano-lab.com, another company providing paint that is equivalent to vantablack. You can buy some, it’s open for everyone.