In the early 1940s, German submarines (U-Boats) were wreaking havoc on Allied forces in the Atlantic Ocean, sinking ships, and threatening to turn the tide of the war. What the Allies of WWII needed was something literally too big to fail. And one inventor working for the British Combined Operations Headquarters (a department of the War Office) had an idea: a giant, floating, mobile and unsinkable island made of ice.

It sounds at first like one of those far-fetched concepts floated by scientists throughout the war — a conflict-ending magic bullet too good to be true — but this proposal led to an actual 1,000-ton prototype approved by Winston Churchill himself and built in secret (and haste).

The Tip of the Ice Ship

Inventor Geoffrey Pyke saw a giant floating ice ship as a natural option in the face of material limitations. Steel and aluminum were in short supply, but water was everywhere. And making it into ice required relatively little energy. So why not use ice instead of steel?

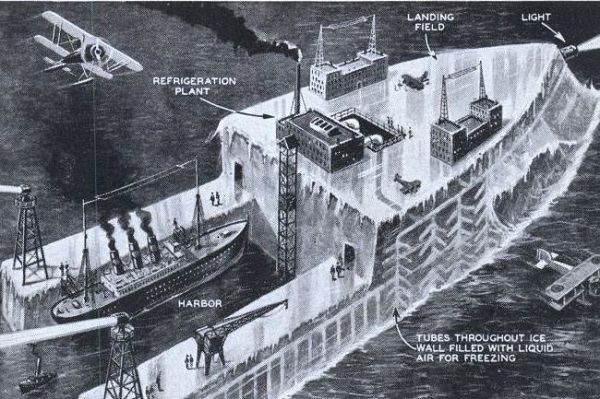

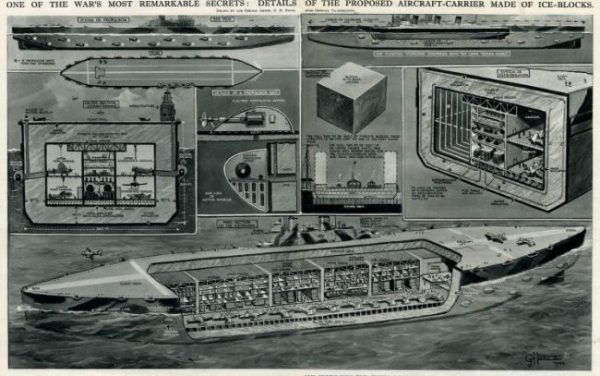

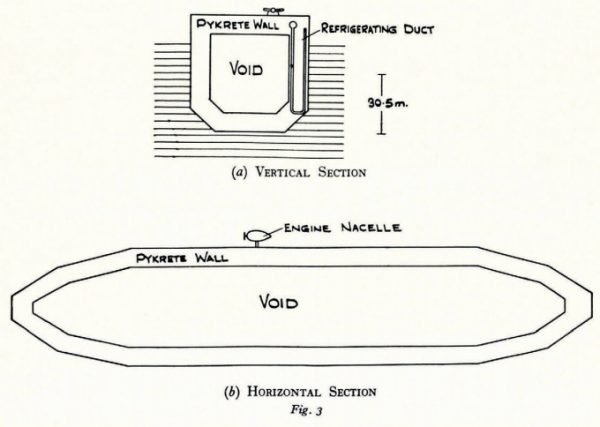

Pyke envisioned a giant aircraft-carrying vessel over a mile long with a solid hull made of ice. It would feature a long landing platform along the top and central void running its length below. This empty space would be able to shelter aircraft beneath the main landing surface. It was designed to be the largest machine ever built on land or water. Its sheer size (and the ability to repair it with water) would make it effectively unsinkable — the ultimate top-secret weapon.

In fact, Pyke was not even the first to envision a ship made of ice — it was something of a running joke in the British military for years prior. And for good reason: ice is brittle and it melts. Icebergs also have a tendency to roll over from time to time. What Pyke needed was a way to keep it from melting quickly and make it stable on the high seas.

But Pyke was regarded by his colleagues in Combined Operations as something of a resident genius. And so he was given leave to pursue this insane-sounding “bergship” idea — he set to work finding a way to turn raw ice into a working sea-worthy vessel.

Perfecting Pykrete

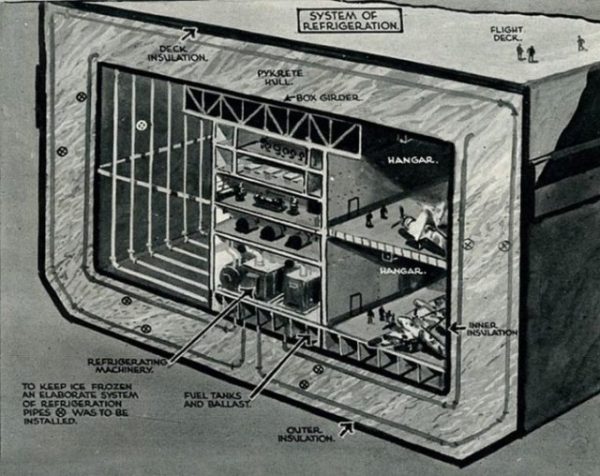

The solution came in the form of something that came to be known as pykrete: a mixture of wood pulp and frozen water. Wood provided reinforcement, making up for deficiencies in pure ice much like steel rebar helps concrete function in structural contexts. Pykrete would float well and melt more slowly. It could be machined like wood and cast like metal. Still, to keep it cold, a ship would need to be insulated and require a system of on-board refrigeration to keep it from melting.

Molecular biologist Max Perutz helped perfect the mixture of ice and pulp, conducting experiments in secret under the Smithfield Meat Market in London (behind a screen of animal carcasses). Later to win the Nobel Prize for work on hemoglobin, Perutz was recruited at the time thanks to his expertise on glaciers and ice crystal structures.

Satisfied with Perutz’s results, Pyke brought his vision to Lord Mountbatten, Chief of Combined Operations, who in turn took a sample block of pykrete directly to Prime Minister Churchill.

According to Mountbatten, he found Churchill soaking in his tub and dropped in the block of pykrete to demonstrate its buoyancy: “After the outer film of ice on the small pykrete cube had melted, the freshly exposed wood pulp kept the remainder of the block from thawing,” reported Mountbatten of the interaction later at a dinner party.

On a Wing and a Prayer

The development of pykrete was not without its incidents and setbacks. At a public ballistics test (aiming to show that pykrete was bulletproof), a ricocheting bullet bounced off a block of the stuff and grazed the leg of an admiral. Stumbling blocks aside, however, a decision was made to pursue the project with all haste.

The sheer scale and audacity of the endeavor called for a name befitting its unbelievability. So they called it Project Habbakuk, in reference to the following passage from the Hebrew Bible: “Behold ye among the nations, and look, and wonder marvelously; for I am working a work in your days, which ye will not believe though it be told you.” (Habbakuk 1:5)

In 1943, a prototype was commissioned. It would be constructed in Canada by conscientious objectors (who opted for alternative service jobs) unaware of the project’s purpose. A 1,000-ton scale model measuring 30 by 60 feet was built on Patricia Lake in Alberta. It was kept frozen in the summer using just a single-horsepower motor, designed to show off the technology under real-world conditions.

A complete, full-scale vessel was to be ordered following a successful test — one that would use at least 300,000 tons of wood pulp, 25,000 tons of insulation, 35,000 tons of timber and 10,000 tons of steel.

Sunk Costs

As the project dragged on, complexities arose and new variables were introduced for the test vessel as well as the huge ship it was supposed to herald. In the model, cold flow (ice deformation) raised the demand for steel as well as insulation.

The full-sized ship would also need to have a range of 7,000 miles, support heavy bombers and be torpedo-proof. It was to be over a mile in length, weigh as much as 2.2 million tons and require as many as 26 electric motors to move and steer across the ocean.

In the end, Project Habakkuk was scrapped thanks to a confluence of circumstances. Its increased steel demands were too high, new airfields had reduced the need for carriers and longer-range fuel tanks were helping aircraft fly further. The estimated price tag of 10 million British Pounds was also seen as simply too high for an experimental craft.

Still, the prototype proved its potential, even once-neglected: it took three hot Canadian summers for the test vessel to completely melt. Its remains can be found at the bottom of Patricia Lake in Jasper National Park, marked by an underwater plaque.

Comments (1)

Share

No mention of MythBusters? I’m surprised :)