A new restaurant called Eatsa opened up a few years back in downtown San Francisco It was designed to be a high-tech affair where people order on iPads and then retrieve food out of a cubby. Instead of placing an order with a waiter or someone behind a counter, customers were directed to punch it in on a screen then walk up to a wall of clear glass cubbies, wait, select the one with their name, then tap to open it. Inside, the food would be ready and waiting.

As a customer, you would never have to interact with a single person if you didn’t want to. You could hop in, grab a custom-made quinoa bowl and then go back to work. Even though this might seem like a very Silicon Valley “meal system of the future,” something very similar to Eatsa existed over 100 years ago in New York.

Meet Me at the Automat

Lorraine Diehl writes about New York history now but when she was a kid she and her grandmother used to go to a restaurant called Horn & Hardart. If you ask anyone who grew up in New York in the 1950s or 60s, they probably went to Horn & Hardart. It was a popular restaurant chain — in many ways, it was the Eatsa of the 20th century.

Diehl teamed up with Marianne Hardart, the great-granddaughter of Horn & Hardart co-founder Frank Hardart, to write the definitive history of this restaurant chain. If the name Horn & Hardart doesn’t ring a bell, you might recognize this restaurant chain by another name: The Automat. “It was the first time you could go up to a wall, put money in, and get food. Hot or cold, fresh prepared,” explains Hardart.

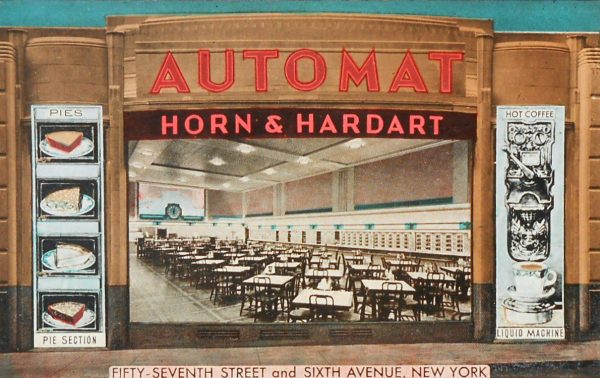

The inside of a Horn & Hardart automat looked like a glamorous, ornate cafeteria — but instead of a human handing you hot food over a counter, you would push your tray up to a wall of little glass cubbies. Each cubby housed a fresh, hot portion of food on a small plate. It could be anything from a savory side of peas or a turkey sandwich to a sweet slice of pie. You would simply put in some nickels, and then the door to that cubby would unlock and you could take the plate that was inside. The food was good but it was also really cheap.

You can see automats in lots of movies ranging from silent films like The Early Bird (1925) to Whit Stillman’s Metropolitan (1990). Setting a scene in an automat created a shorthand for a certain kind of American: one who wanted to go out to eat but didn’t have the budget. In reality, however, even the rich and famous enjoyed eating at the automat.

Diehl says gives some famous examples, like “Gene Kelly when he was doing Pal Joey on Broadway […] and Gregory Peck [loved] their scrambled eggs. Counts and countesses — foreign dignitaries would say we’ve got to try this!” These movie stars and dignitaries would sit down at the automat next to people who were flat broke.

When Joe Met Frank

The story of the automat started when Joe Horn met Frank Hardart. Horn had put an ad in a local Philadelphia paper seeking a business partner and together the pair opened a luncheonette in Philadelphia in 1888. For a while, it was just a normal luncheonette with famously good coffee. This all changed when Frank Hardart went to Germany on vacation and discovered early German vending machine technology and brought it back to Philadelphia.

What he observed was a kind of overly complicated German vending contraption with food behind windows that operated as a sample display of what one could order. Customers would deposit a coin and wait while someone in the basement cooked it and then cranked it up in a dumbwaiter. “It was a very convoluted way of getting your food but everyone loved the novelty of it […] so they perfected it and then they brought it to New York City” says Diehl.

The automat caught on fast, but not because of the technology. That was just a gimmick to get people in the door. People initially came for the novelty but came back again and again because it was good food for cheap. The technology was just a Mechanical Turk. The automat appeared automatic from the outside, but behind the walls, there were people running around and replacing the food behind the scenes.

Past the vending walls were scores of workers — many of whom were recent immigrants — rapidly replenishing the food into the cubbies and darting out to bus tables and clean dishware. As automats expanded to more locations, all of the cooking was moved to offsite commissaries. These separate kitchens could take up a whole city block. They were packed full of vats of sauces and pies by the hundreds, which were dispatched hot and fresh to all the automats throughout the day.

The automats themselves were gorgeous. It was one of those rare brands that had appeal across economic classes, like IKEA or Target. The automat was a place where anyone could eat.

Before McDonald’s, Horn & Hardart was the largest restaurant chain in America and one of the largest by volume in the world even though it had locations in only two cities. It was hard for New Yorkers and Philadelphians to imagine that Horn & Hardart could ever disappear because it had become such an institution — it was like imagining Starbucks disappearing today. What happened to the automat was in many ways the story of the American city — white flight and mass migration to the suburbs impacted everything. Americans had new homes, new cars and new lifestyles, which changed how people ate.

“It became very trendy for women to be stay-at-home mothers, taking care of new homes, using their new kitchens, taking care of the family — and that meant less eating out,” explains Lisa Hurwitz, a filmmaker working on a documentary about the Automat.

In the 1950s, when people went out to eat, they weren’t satisfied with twenty-cent steaks anymore. If pressed for time, they could opt for fast food, but when people wanted to sit for a meal they wanted white tablecloths, attentive waiters and fancy food that couldn’t be cooked at home. “People had more money to spend,” explains Hurwitz. “They were more inclined to have fewer meals out but to have nicer meals.”

Horn & Hardarts were getting old and outdated. Meanwhile, customers and city governments were investing less and less in the increasingly neglected inner cities around them. As Horn & Hardart got less popular, the food turnover wasn’t as high and it wasn’t as fresh. Meanwhile, the heads of the company were being pushed out by executives who believed the future was in fast food.

The new heads of Horn & Hardart realized their greatest asset wasn’t their restaurants but their real estate. Many of the prime Horn & Hardart locations were franchised into fast food restaurants. Some of these locations became some of the first Burger Kings and Arby’s franchises in Manhattan.

Let Them Eat Take-Out

The automat lasted the better part of a century, which is incredible for any business. The last automat in New York, which scraped by as a bit of a gimmick, finally closed in 1991. “People aren’t looking for an all-robot kind of experience,” says Gwyneth Borden, the executive director of the Golden Gate Restaurant Association. “When they walk in, they want it to be easy and convenient — and … if they have an issue, [they want] to be able to communicate to someone who can take care of them.” She says that 2015 was the first year in the United States when people spent more money on dining out than on groceries.

Demand for restaurants is up, which means there’s a national labor shortage of restaurant workers, especially in expensive cities like San Francisco. The median cost of a one-bedroom apartment is now $3,700 a month, which begs the question: how does one pay that while working in a restaurant? “As labor costs overall have risen, it’s harder to find people to work in farming, it’s hard for people to work in restaurants, so you have to pay people more,” says Borden. Restaurants have been trying to get by with fewer people using self-ordering screens or counter service where you grab a number for your table. But this can be taken too far. Borden says if you look at Yelp or Trip Advisor, you see in peoples’ reviews that service is a really important factor. Reviewers might write about the food not being very good, but it’s a bad service experience that will drive them to leave a bad review.

So rather than hiding workers in the back and automating the front of the house (like Eatsa or the automat) some new automated restaurants are trying to flip the system. They want the food to be served entirely by humans, but cooked by robots.

Eatsa’s two locations in San Francisco are now shuttered with no signs of when they’ll open again. Eatsa wouldn’t go on record for an interview, but their PR representative said that now Eatsa is focused on selling their serving technology to other chains — more restaurants where you can order on a screen and pick up from a cubby.

And it’s not just those select chains that are contracting with Eatsa. At McDonald’s now (and a number of other chains) it’s pretty common to order on a screen. A salad-making robot named “Sally” is being put in a restaurant chain based in Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama. There are new iterations of vending machines and faceless delivery and robot chefs popping up everywhere. Horn & Hardart restaurants may be gone, but more and more chains are becoming automats.

Comments (16)

Share

They still exist in Netherlands and are called automaat. https://www.yelp.com/biz_photos/smullers-duivendrecht?select=IkJeOJjEGEmOg-upexzrMw

Indeed! The Febo has built their whole brand around it, and they are still used but only for snacks and fastfood. In Dutch we would say ‘trek een kroket uit de muur’, which is translated to ‘pull a kroket out off the wall’.

This is true. I’ve come across 3 in just the past few days, for example https://www.google.com/maps/uv?hl=en&pb=!1s0x47c69f870816207b%3A0xc0e4ede1ea11517e!2m22!2m2!1i80!2i80!3m1!2i20!16m16!1b1!2m2!1m1!1e1!2m2!1m1!1e3!2m2!1m1!1e5!2m2!1m1!1e4!2m2!1m1!1e6!3m1!7e115!4shttps%3A%2F%2Flh5.googleusercontent.com%2Fp%2FAF1QipNTCdwKcGItBLmCfkVSj7Xcs_w74ip-EF6nyLlH%3Dw814-h605-n-k-no!5sGoogle%20Search!11b1&imagekey=!1e10!2sAF1QipPg6sjDNPFQ9nHsZpa6yNgLptwpFcZspIzSQHqY&viewerState=ga#

I like the idea of not having to interact with a waiter or not having to leave a tip. With fast food servers I feel pressured to make decisions, can’t spend time exploring the ingredients, and end up in a line to place my order. Or worse, waiting, Alone. I rarely eat out with anyone else; eating out isn’t sociable for me, it’s just a need.

McDonalds is quickly moving in a direction that I like on that front, even tho I don’t care for their food much. I can order two triple cheeseburgers and couple clip and not feel like I’m being judged.

Cities that only have sit down diners frustrate me in that regard. It’s wasted time, awkward, and the bill is often outrageous. I am envious of Japan in some ways here; surprised Japan wasn’t mentioned really.

This podcast takes an anti-automat attitude from the very start, which soured my enjoyment of it. Different personalities and priorities I guess; I understand the desire to be more human in an ever more disconnected world, but it’s a world many feel rejected from. As noted, it’s fun to hate these days and not consider other’s views.

As always I enjoyed the episode but what about Bamn! Automat in NYC? It appears to have been open until 2009.

I remember stopping by on one of my first solo trips to Manhattan.

https://youtu.be/GYKslfnQebc

ttps://yelp.to/qTKq/duy47avihX

https://ask.metafilter.com/124123/NYC-folks-What-happened-to-the-BAMN-automat/

There’s a very funny take on the Horn and Hardart company name in the form of a parody piece written by Peter Shickele, The Concerto for Horn and Hardart. This required the invention of an instrument called a Hardart, which required coins for operation.

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Concerto_for_Horn_and_Hardart.

As a kid in the 1980s, I loved going to the last Automat in New York.

Great episode, I really discovered something new about American culture.

So is this the explanation for the photo on the cover of R.E.M.’s album, “Automatic for the People”? (I assumed that photo was from Athens, GA, their home town.)

Never got to try Eatsa at home in San Francisco, but funnily enough I got to try their technology when visiting Chicago at a place called Wow Bao. Funnily enough the majority of the other people there were Door Dash delivery drivers.

I did try eatsa! It was goood I appreciated the high customization level, kind of like the 5 desserts you don’t feel as judged to change 5 of the 8 things :)

Does anyone know what is the advertising podcast mentioned in the food as section?

I remember being taken to one of them quite a few times when I was a child. Must have been in the early 60s. I seem to recall it was somewhere around 34th street. Thank you for bringing back fond memories of my childhood. It feels as though it was yesterday!

I can’t believe didn’t mention the phenomenon of UberEats and the other apps, the new Automat.

Really surprised that the last one closed as late as 1991. I would’ve thought that by that point it would be a tourist attraction.

It may sound tacky, but I wonder how it would work if it had been marketed as a themed restaurant? There was a lot of talk about how fun automats were for kids. I think getting a pie from a wall would still be pretty cool for them. I don’t know… I could never convince my parents to take me to a Rainforest Café as a kid, but maybe they would’ve enjoyed an art-deco food palace.

Having been a New Yorker for most of my life, I remember in the seventies and into the eighties there was the last Horn and Hardart on West 57th St. You could fine anyone there, as its mass appeal never changed. To this day thay had the best chocolate cream pie ever! It was fabulous fun. Besides a curiosity it really worked.

Something crazy just happened: I was just reading an old family history that my father gave to me, and in it my great-great-grandfather claims to have invented the automat mechanism (he was a mechanical engineer in NY) and had it stolen by Horn and Hardart. He later attempted to enforce his patent – but gave up when H&H protested.