If you live in an American city and you don’t personally use a wheelchair, it’s easy to overlook the small ramp at most intersections, between the sidewalk and the street. Today, these curb cuts are everywhere, but fifty years ago — when an activist named Ed Roberts was young — most urban corners featured a sharp drop-off, making it difficult for him and other wheelchair users to get between blocks without assistance.

Roberts was central to a movement that demanded society see disabled people in a new way. He’d grown up in Burlingame, near San Francisco, the oldest of four boys. He was athletic and loved to play baseball. But then, one day when he was 14 years old, he got really sick.

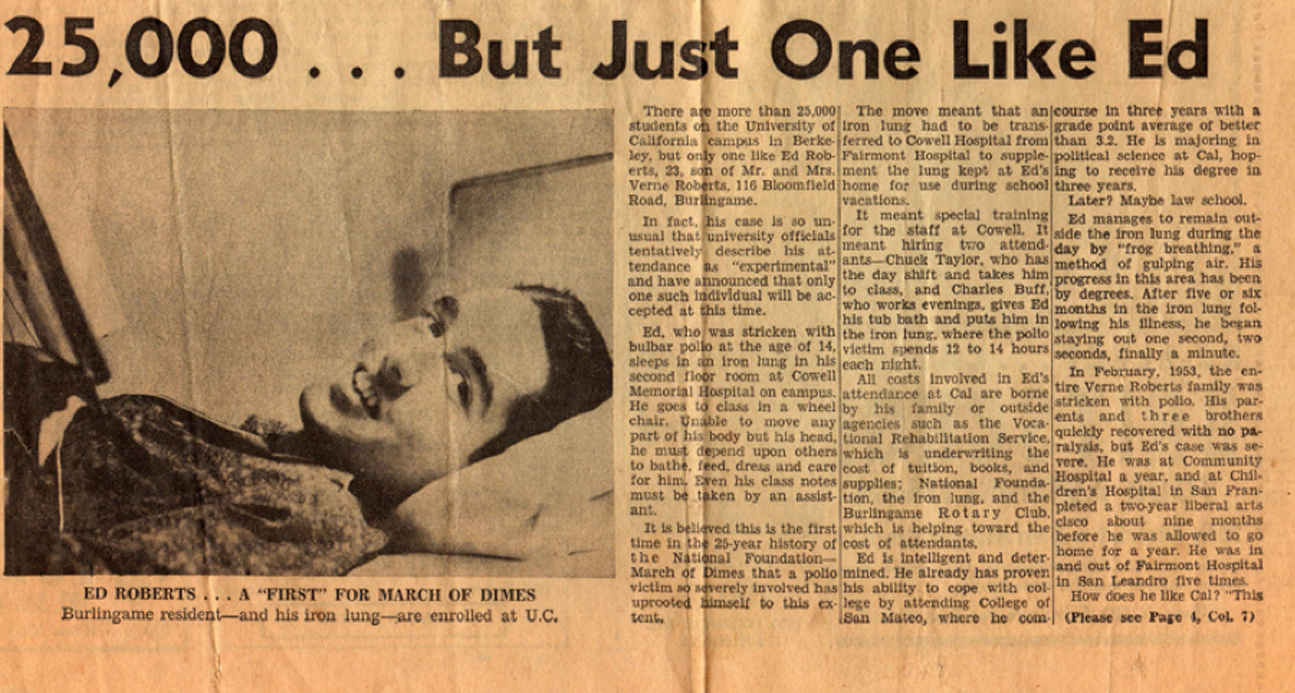

He had polio, which damaged his respiratory muscles so much that he needed an iron lung to stay alive. The polio left Roberts paralyzed below the neck, only able to move two fingers on his left hand.

In order to escape his iron lung once in a while, Roberts taught himself a technique called “frog breathing,” a deep-sea divers’ trick of gulping oxygen into the lungs, the way a frog does. For polio survivors, whose weakened breathing muscles weren’t strong enough to inhale that needed oxygen, “frog breathing” meant a person could get out of the iron lung for short stretches of time. Roberts was told it was bad for his health, but he kept doing it, determined to live on his own terms.

Roberts was tenacious, but everything was hard. He needed the iron lung while he was asleep, but during the day he stayed in school, going to campus once a week. When Ed left the house, his family would run the maneuvers, helping him navigate a world that wasn’t built for a person in a wheelchair. They’d lift him over curbs, and up and down stairs. When his mother, Zona Roberts, went out with him alone, she would enlist strangers to assist.

Roberts graduated from high school, then from a local community college, but in 1962, when he wanted to go on to U.C. Berkeley, the university initially turned him down. Among other things, administrators weren’t sure where he could safely live — his iron lung wouldn’t fit into a dorm room. Eventually, someone suggested housing Roberts in the campus hospital, inside a patient room remade into a living space.

On campus, an attendant would wheel Roberts to each class, where he would recruit a classmate to help him take notes — they would use a piece of carbon paper to create a copy for him. “It’s such a simple way to take notes,” Roberts recalled, “and of course to meet people and get them involved with you. So there were all these little gimmicks.” Roberts did so much studying and reading that the mouth wand he used to turn the pages of books started to push his teeth out of shape.

His story began to make newspaper headlines. Soon, a second quadriplegic student moved into Roberts’ makeshift hospital dorm— a young man who’d been paralyzed in a diving accident and was initially told he should just get used to life as a shut-in. Then a few more arrived, both to live in the hospital and to find lodgings off campus. The word started to spread: something unusual was going on at Berkeley.

These students had profound and visible disabilities. The state paid special attendants to heft their wheelchairs up staircases and into lecture halls. It was hard to miss the new presence on campus.

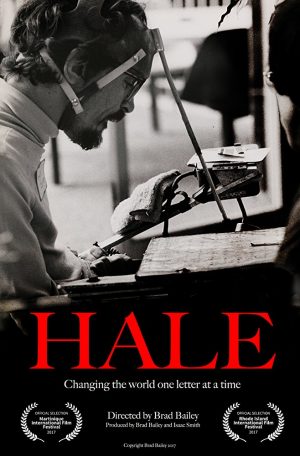

And all of this was happening during the 1960s, “a time of lots of protests, and lots of reform, and lots of change,” explains Steve Brown, co-founder of the Institute on Disability Culture. On the Berkeley campus, the hospital housing students also became the headquarters for an exuberant and irreverent group of organizers. This group called themselves the Rolling Quads and it included Roberts as well as Hale Zukas, an assertive guy with cerebral palsy who communicated with a word board and a pointer strapped to his head.

Like other coalitions of disabled young people around the country, the Rolling Quads started using a new kind of language to talk about their needs and rights. They were advocating for what was then a radical idea: that people with disabilities had civil rights, too. The right to education, to jobs, to respect, to real inclusion in public life. This all fit right into the revolutionary spirit of the 1960s and early 70s.

One member of the Rolling Quads, Deborah Kaplan, explains the widespread cultural stereotypes the group was trying to take apart: “That having a disability is a fate worse than death. That we should be pitied. That if we do anything we are brave, and yet [we’re] really not real people.” These kinds of views were reinforced by events like the annual Jerry Lewis Telethon. The telethon was the late comedian’s annual marathon fundraiser for muscular dystrophy. He mugged for the camera, and brought in celebrity singers, and spent a lot of time smiling down at cute, well-dressed children in wheelchairs. The rising generation of disability rights activists hated it.

“We would just cringe every Memorial Day weekend, knowing that all these people were watching Jerry Lewis squeezing money out of people by dramatically playing up the most horrid stereotypes about disability that we had to combat,” Kaplan explains.

Back at Berkeley, the Rolling Quads — and Ed Roberts in particular — were one big antidote to the Jerry Lewis telethon. Roberts flirted with women, got arrested in college for peeing outside a bar, and told dark jokes about quadriplegia. A testing counselor once pronounced Roberts to be “very aggressive” — he liked recounting his response: “Well, if you were paralyzed from the neck down, don’t you think aggressiveness would be an asset?”

Back at Berkeley, the Rolling Quads — and Ed Roberts in particular — were one big antidote to the Jerry Lewis telethon. Roberts flirted with women, got arrested in college for peeing outside a bar, and told dark jokes about quadriplegia. A testing counselor once pronounced Roberts to be “very aggressive” — he liked recounting his response: “Well, if you were paralyzed from the neck down, don’t you think aggressiveness would be an asset?”

“The nature of access, of being included, meant that you had to in some ways force yourself upon the world,” says Lawrence Carter-Long, of the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund.

“Because the tendency, the programming, for the rest of the country — even here in Berkeley at first — was to say, ‘We don’t want to see that. You’re going to make those normal people uncomfortable!'”

But by the time Ed Roberts was in graduate school at Berkeley, the disabled students were noticeably and unmistakably part of the community. Even more so because some were zipping around in power chairs, which had been invented to help wounded veterans and were starting to be more available to the general public.

Roberts got interested in power chairs when he first watched another quadriplegic try one out. And he now had a new portable ventilator that attached to his wheelchair. So even though he still used the iron lung at night, he could stay away from it a lot longer. And… there was a girl. Which, he remembers, made it “ridiculously inconvenient for me to have my attendant pushing me around in my wheelchair with my girlfriend. It was an extra person that I didn’t need to be more intimate.”

But think about this. For more than a decade you’ve been able to get around because somebody’s behind you pushing your chair, and now you’re under your own power. You get to leave that wheelchair attendant behind, but still, you have to contend with… curbs.

“If you’re trying to get across the street and there are no curb cuts, six inches might as well be Mount Everest,” says Lawrence Carter Long. “Six inches makes all the difference in the world if you can’t get over that curb.”

The power chair riders — actually all the wheelchair riders — needed what we now call “curb cuts” — those slopes at the corners that make it easy to roll between sidewalk and street.

The Early History of Curb Cuts

Back in the 1940s and 50s, there were a few communities across the country where people had tried to make elements of the built environment more accessible. For example, there was a coach in Illinois working with disabled soldiers who badgered reluctant officials at the University of Illinois — until finally, the school set up a rehab and education program with wheelchair sports and wood ramps into buildings.

Historian Steve Brown discovered another example in Kalamazoo, Michigan. Kalamazoo had extra high curbs. After WWII, a retired veteran got so fed up watching other disabled vets struggling to cross the street that he persuaded city officials to cut ramps into the sidewalks at four downtown corners.

But by the late 1960s and 70s, the new wave of young disabled activists wasn’t going to wait around for the occasional enlightened college coach. They demanded. They were insistent. They didn’t wait for permission.

To this day, stories circulate about the Rolling Quads riding out at night with attendants and using sledgehammers to bust up curbs and build their own ramps, forcing the city into action. But Eric Dibner, who was an attendant for disabled students at Berkeley in the 1970s, says “the story that there were midnight commandos is a little bit exaggerated, I think. We got a bag or two of concrete,” he elaborates, “and mixed it up and took it to the corners that would most ease the route.” While it did happen at night, they only hacked a few curbs.

In reality, most of the progress made by the Rolling Quads was a little more bureaucratic. One day in 1971, the group showed up at the Berkeley City Council. Ed Roberts, by then a political science graduate student, was there. And so was Hale Zukas, who was learning Russian and finishing a math degree. So were a lot of their friends, both disabled and not. Together, they insisted the city build curb cuts on every street corner in Berkeley. And their call to action sparked the world’s first widespread curb cuts program. From the city council minutes on September 28, 1971: “Declaring it to be the policy of the city that streets and sidewalks be designed and constructed to facilitate circulation by handicapped persons within major commercial areas … That curb cuts be made immediately at fifteen specified corners …. The motion carried unanimously.”

Beyond Berkeley

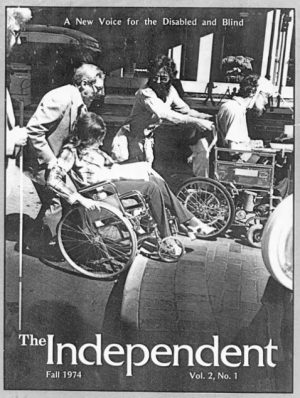

By the mid-1970s, the disability rights movement was growing and spreading, with groups around the world advocating for changes in the built environment to enable more independence. This didn’t just mean curb cuts, but also wheelchair lifts on buses, ramps alongside staircases, elevators with reachable buttons in public buildings, accessible bathrooms, and service counters low enough to let a person in a wheelchair be attended to face-to-face, and more.

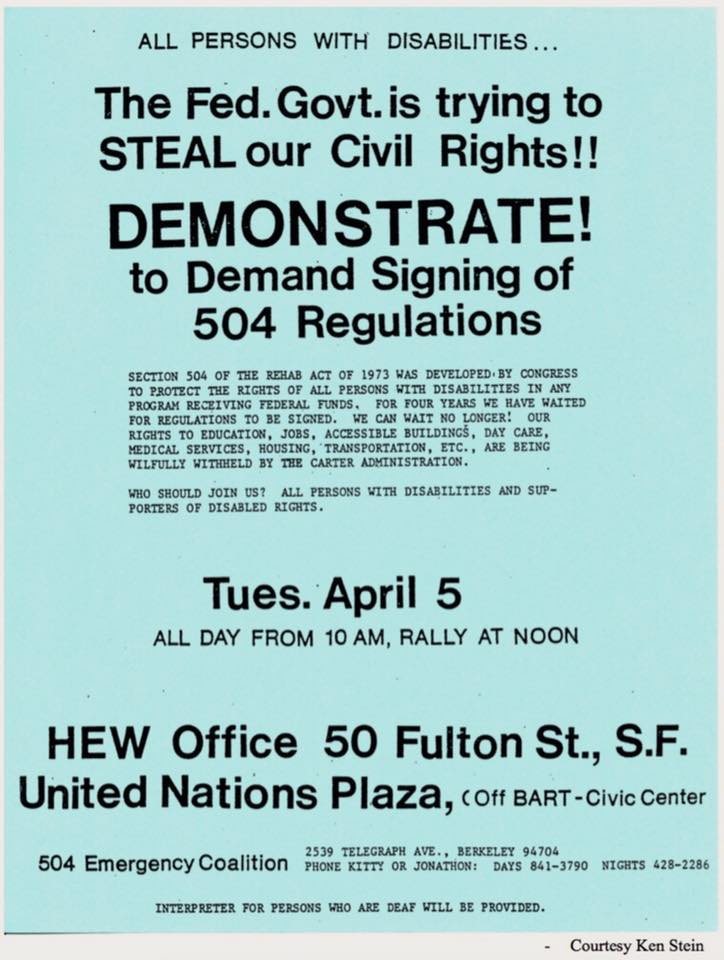

In 1977, disability rights protesters hit federal office buildings in eleven cities at once. They were pushing the government to act on long-neglected rules protecting the disabled in all facilities taking federal money. The protest in San Francisco turned into a month-long sit-in, with steady news coverage of people in wheelchairs, taking care of each other and refusing to leave until action was taken.

In 1980, disabled people in Denver staged a protest demanding curb cuts. They’d already blocked traffic until city transit officials promised to put wheelchair lifts on all the buses. Demonstrators in wheelchairs leaned over, for the photographers, to whack at concrete curbs with sledgehammers.

And in 1990, when the sweeping Americans with Disabilities Act was hung up in the House of Representatives, disabled demonstrators left their wheelchairs and crawled up the marble steps of the Capitol building to make sure the bill went through.

The ADA wasn’t the first federal legislation designed to remove barriers for disabled people, but its reach was unprecedented. It mandated access and accommodation for the disabled in all places open to the public — businesses, lodgings, transportation, employment. It had qualifiers, to be sure — the ADA required only what was “reasonable,” for employers and builders and so on. There was a lot of argument about that word. But at the bill’s signing ceremony in 1990, President George H. W. Bush spoke with emotion about the recent fall of the Berlin Wall, which had divided communist East Germany from the West:

“And now I sign legislation, which takes a sledgehammer to another wall, one which has for too many generations separated Americans with disabilities from the freedom they could glimpse but not grasp. And once again we rejoice as this barrier falls, proclaiming together, we will not accept … excuse [or] tolerate, discrimination in America.”

The Legacy of Ed Roberts

Ed Roberts, who U.C. Berkeley officials once thought was too crippled for their university, finished his master’s degree, taught on campus, and co-founded the Center for Independent Living, a disability service organization that became a model for hundreds of others around the world. He also married, fathered a son, divorced, won a MacArthur genius grant, and for nearly a decade ran the whole California state Department of Rehabilitation Services. He was 56, an international name in independence for the disabled, when a heart attack killed him.

A special memorial was scheduled for him at the annual march and meeting of the National Council on Independent Living in Washington, D.C. Marchers followed Roberts’ empty wheelchair which was being dragged along by his attendant, until they reached the Senate office building. Once inside, speakers got up to honor Roberts’ life and legacy. Senator Tom Harkin from Iowa gave a eulogy, noting that when Martin Luther King Jr. died, they built statues to honor him. But Harkin said there was an even better way to honor Ed Roberts, a warrior for another kind of civil rights. Barriers would be torn down in his name. Every curb cut would become a memorial for Roberts.

Today, Roberts’ wheelchair is stored at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, and remains on permanent display on their website. But the struggle continues — curb cuts are common now, but they’re not at every intersection, even in Berkeley. And a lot of assumptions persist about what people with disabilities can do, achieve, and enjoy.

Today, Roberts’ wheelchair is stored at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, and remains on permanent display on their website. But the struggle continues — curb cuts are common now, but they’re not at every intersection, even in Berkeley. And a lot of assumptions persist about what people with disabilities can do, achieve, and enjoy.

“We’ve not yet accomplished full inclusion,” says Lawrence Carter-Long. “We have managed to make it easier, by and large, for people to get into the building. But have we done the work that’s going to make it easier for them to get the education? For them not only to have a job, but have a career? Those things still don’t exist for many people, even in Berkeley.” The work remains.

Comments (17)

Share

I’m pretty sure that curb-cut photo up top is the NE corner of the block I live on in Mpls. I walk over that curb cut every day on the way to the bus. What a fun, weird coincidence. Thanks, 99pi!

Ed’s attended who brought the chair to Washington from California was Mike Boyd, and he wasn’t dragging the chair in the March. I was. When I saw he had arrived I went over to say hello to him. He was rigging the bungee cords around Ed’s chair. He asked me if I wanted to do this without elaborating, and I didn’t hesitate. Tom Olin is probably the only person on the planet who has pictures of this. It was May 15, 1995. Walking with Mike behind me and keeping the bungee cord from getting tangled was Clifton Perez.

Very cool program, thx for posting. In Ontario, Canada’s first province to do so, we are tackling built form of our main avenue businesses to enable compliance by 2025. There are 60,000 of these storefront and second story, bias and they are vital to rgw economy. Oddly, many bizs think that just because their buildings are heritage and inaccessible by design, they are exempt. Our program will help them find ways to comply. Stumbling upon this piece was a happy coincidence and I’ll be sure to share it with our AODA Advisory Group on the OBIAA.

Thank you for this detail, Michael! I looked hard for visuals and audio of that event, but had no luck–and appreciate the additional info about who did the actual dragging It is an amazing story, the way you left the chair at the Smithsonian. Regards–Cynthia G.

Is this not captioned? I can’t figure out how to see the captions if they are there.

Never mind. I found the transcript.

I listened to this episode while commuting to work today in my wheelchair. I crossed a dozen or more curb cuts along my route.

The episode made me realize that, as someone who was born a decade after the heyday of the Rolling Quads, I have benefited from their struggle in ways I’ve been mostly unaware of. I’d only vaguely heard of Ed Roberts before today, but thanks to the work he and his peers did, I’ve been able to do “normal” things like attend college, get a job, socialize, marry, become a dad, and travel the world — at least, the parts of it that have embraced wheelchair access.

I’m grateful to those pioneers, and to 99 PI for educating me about them. Their stories should be taught in schools alongside those of activists like Martin Luther King, Cesar Chavez, Gloria Steinem, and Harvey Milk.

Here is a discussion of the Americans with Disabilities Act and sidewalks, including the Barden v. Sacramento court case that determined that sidewalks are indeed covered by the ADA.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ksqfGz6Y0v0

You should do an update to cover raised crossings – which are a much more inclusive design solution, safer, and don’t force you to go through puddles.

Great story,

One cool thing I noticed in Japan was that those half dome textures extend continuously along the sidewalk. Great idea for the blind

I listened this morning, thanks to the time shifting nature of podcasts. I thought of a “curb cut effect” that wasn’t mentioned. Alexander Graham Bell Bell was a teacher of the deaf before he became an inventor. He was working on an amplification device for the hearing impaired when he invented the telephone. That’s a pretty profound, world changing curb cut effect.

Thanks for the great show.

Just finished listening to brilliant episode on Curb Cuts, or Dropped Kerbs as they are known here. You now need to continue with the obvious sequel on Tactile Paving, the need for which arose directly from providing dropped kerbs.

I happened upon this episode by random chance. I am a civil infrastructure designer that grew up in the 80’s. It never occurred to me there was a time when curb cuts didn’t exist. As a designer, I draw curb cuts all day everyday. This episode has challenged me to consider what I am not designing. I ask myself; what obstacles am I unknowingly putting up for people, and how can I do better.

What a completely fantastic comment David.

Curb cuts didn’t exist in my native Montenegro until the early 2000s. I’m proud to have been a part of a team that worked to raise awareness of the problem through pointed media campaigns, which lead to all kinds of accessibility reforms and legislation. Now curb cuts are everywhere, just like ramps etc.

My uncle was a member of the Rolling Quads at Berkeley and he worked extensively with Ed Roberts at the Department of Rehabilitation as his deputy director. I know they also work on laws regarding service animals. He had some pretty interesting stories of his times at Berkeley. I think there was a time the Ed was living at my uncles place, I think I remember seeing the iron lung at his house. If anyone is interested, here is a link to transcripts of interviews fro the 90’s. http://content.cdlib.org/view?docId=kt9t1nb3t1&query=&brand=calisphere

What a great episode! As an industrial designer I am familiar with universal design, but most of the time it’s quite difficult to implement. I found curb-cut effect very fascinating. Also wanted to point out that those ,,7 principles of design,, are not complete. A famous designer Dieter Rams has a book called ,,Ten principles for good design,,. According to Dieter Rams, good design:

Is innovative

Makes a product useful

Is aesthetic

Makes a product understandable

Is unobtrusive

Is honest

Is long-lasting

Is thorough down to the last detail

Is environmentally friendly

Involves as little design as possible