The line to enter Barcelona’s most famous church often stretches around the block. La Sagrada Família, designed by Antoni Gaudí, draws so many people to see it that the neighborhood is congested with

tour buses and taxis and scooters. It’s estimated that some three million people went inside of the church in 2016, and another seven million came just to stare at the outside of the strange, behemoth structure.

There are a lot of Gothic churches in Spain, but this one is different. First, it doesn’t look like a Gothic church. It looks like it was built out of bones, or sand—it’s organic looking, somehow. But there’s another thing that sets it apart from your average old Gothic cathedral: it isn’t actually old.

Gaudí wasn’t able to build very much of his famous church before he died in 1926. Most of it has been built in the last 40 years, and it still isn’t finished. Which means that architects have had to figure out, and still are figuring out, how Gaudí wanted the church to be built.

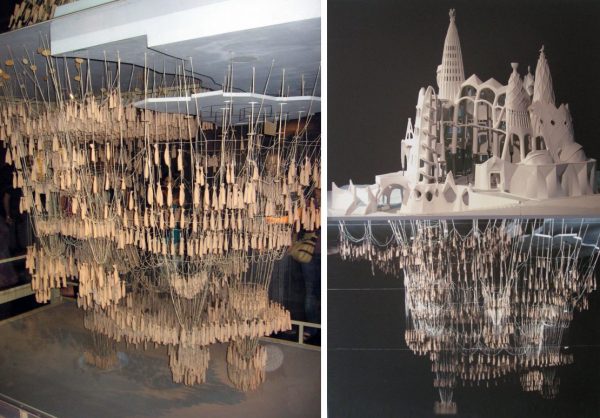

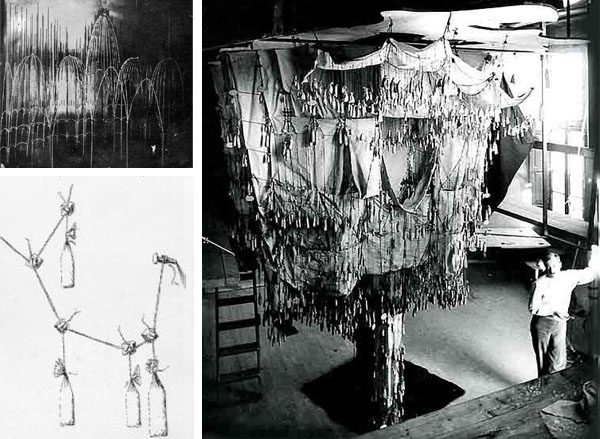

Before he died, Antoni Gaudí left elaborate plaster models detailing his plans for finishing the church, but about 80 years ago, they were all basically destroyed.

With very little to go on, it hasn’t been easy for the new architects to recreate and understand the vision of Antoni Gaudí. And there are people who think they shouldn’t even have tried— that the building should have stopped after Gaudí’s death. But it didn’t. In fact, it’s currently the longest running construction project in the world.

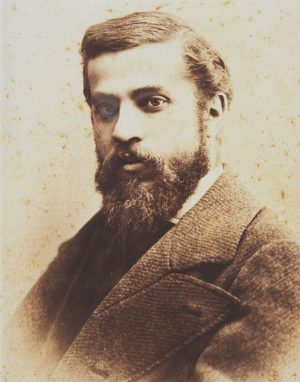

Antoni Gaudí grew up in a little town called Reus which, like Barcelona, is part of a region of Spain called Catalonia. And although he’s become one of Spain’s most famous architects, Gaudí would never have identified as “spanish” He was Catalonian, through and through.

As a child, growing up in Catalonia, Gaudí was enthralled with the natural world around him.

He seemed to absorb essential lessons from the patterns and shapes he saw in nature. A dried out snake’s skeleton, a snail, a honeycomb— these were nature’s perfect constructions. And for Gaudí, a deeply religious Catholic, God was the master architect of these flawless organic structures.

Eventually Gaudí left his small town in the countryside and moved to Barcelona for university and then architectural school. When he graduated in 1878, the director of the school declared: “Gentlemen, we are here today either in the presence of a genius or a madman!”

Gaudí began his career at a difficult moment in Barcelona. The industrial revolution had brought thousands of workers from the countryside into the city for factory jobs. They were toiling in terrible conditions, packed into filthy tenements, drinking dirty water. Diseases like yellow fever and cholera were rampant.

Meanwhile, a fundamentalist Catholic named Josep Boccabella believed the misery of the poor in Barcelona was punishment for their sins, and he set out to build a church—one meant to inspire the common folk to live a religious life.

The church would be dedicated to Mary, Joseph and Jesus—the holy Family (La Sagrada Família). Bocabella’s first architect, Francisco de Paula del Villar y Lozano, quit after a year, having barely begun on the church, and Bocabella chose 29-year-old Anton Gaudí to continue the work.

La Sagrada Família would be built in the Neo-Gothic style which was popular at the time in Europe, but Gaudí also wanted this creation to be something completely unique – inspired by nature, and by God.

Gaudí would never allow the building to outshine God’s creations however, so he set a limit on how tall the church would ever get. La Sagrada Família would be one meter (or about 3 feet) shorter than Mount Montjuïc in Barcelona. Just to keep it humble.

In 1883, Gaudí began his work on the crypt, which had already been started by the previous architect. The crypt is essentially a small church under the larger church and a place where important people are buried. Services were held in the crypt while Gaudí took his time designing the rest of the church.

When the crypt was finished, Gaudí began work on one huge wall of the building — the nativity facade, which he would work on for the remainder of his life.

Gaudí was a sculptor as much as an architect, and the wall would be full of stone sculptures, depicting biblical scenes. It eventually became crowded and cluttered and teeming with life.

Throughout the years, Gaudí worked on other projects in Barcelona. His work is peppered all over the city. In palaces, pavilions and extravagant homes, the organic curves of his sinuous and skeletal architecture are unmistakable.

But La Sagrada Família is the project that consumed him. In 1926, 73-year-old Antoni Gaudí, who was never married, was living alone. He spent many nights sleeping in his studio at La Sagrada Família—obsessed with his magnum opus.

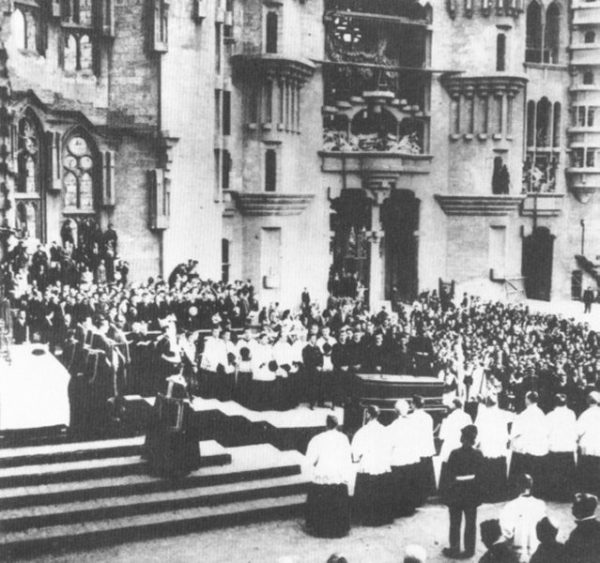

On June 7th of that year, Gaudí was crossing some railroad tracks and was hit by a tram. He died three days later, and was buried in the La Sagrada Família crypt. It is estimated that hundreds of thousands of people mourned him in the streets.

When Gaudí died, he left behind a largely unfinished church. What stood was a massive wall (the nativity facade), one bell tower, and the crypt. Fortunately, he had left behind detailed drawings and models outlining exactly how he wanted his magnum opus to be built.

For ten years, work on La Sagrada Família continued very slowly. The patrons of the building wanted it to continue and much of Gaudí’s loyal team stayed on.

Then, in 1936, the Spanish Civil War began. The Republicans, an alliance of various leftist parties, fought against the Nationalists, an alliance of fascists and other conservatives, led by General Francisco Franco. The Nationalists also had the support of most of Spain’s Catholic clergy.

On the 18th of July, two days after the start of the Spanish Civil War, a group of young anarchists broke into the studios of Gaudí, smashed his models and burned the architectural drawings. Their attempt to bomb the Nativity facade, however, failed.

Catholicism was under attack during the war, and by the end of it, 40 churches in Barcelona had been destroyed and 12 people associated with the Sagrada Família project – including some of its managing patrons and clergy – had been killed.

The war ended in 1939 with a victory by Franco. When it was over, workers returned to Gaudi’s studio to salvage what they could. The only thing left were a few photos, and some basic drawings in journals. Everything that detailed the architectural intent was gone.

For the next couple of decades, the remaining architects tried to figure out how to move forward—a difficult task without Gaudí’s plans and models. In the 1960s a group of intellectuals and architects, including Le Corbusier and Alvar Aalto, wrote an open letter opposing the continuation of La Sagrada Família. Gaudí wasn’t only an architect, they argued, but an artist whose work should be left as it was. They thought the Nativity Facade should be left up as an homage to Gaudi, but that all other work should cease.

But the patrons of La Sagrada Família would have none of it. The building was never supposed to be an homage to Gaudí, they argued. It was always about something bigger.

By the 1970s, another huge facade of the building was going up: the the passion facade. This facade depicts a stark and brutal scene of the crucifixion designed by sculptor Josep Maria Subirachs.

But the church still had no interior, and no roof. It was just walls and tower, a construction site, open to the rain.

In 1977, a 20 year-old architect named Mark Burry went to Barcelona to study Gaudí. By accident, he met the two elderly architects who were directing the construction project. These architects, former students of Gaudí himself, were ready to move on to the interior of the building, but they didn’t know how to proceed. They knew it was theoretically possible to create the rest of the church, But it was a monumental task. They pointed Burry to the broken models and asked him to join the team.

For a year, Burry worked with the models, trying to extrapolate the geometry of the rest of the church based on the pieces he had. After a year, he’d managed to draw out architectural blueprints for one window. It was a start.

Burry returned to New Zealand for a time, and when he came back to La Sagrada Família in the early 90s, he found he had a strange new office-mate: a computer.

The computer was installed with architectural software, but it couldn’t handle the complexity of Gaudi’s designs. Burry wondered if there was anyone else who designed with similar geometric complexity, and finally he landed on it: people who design airplanes. He started using aeronautical software to figure out an architectural strategy for the interior of the church.

In this exploration of new software, he discovered parametric design, which uses computer algorithms to allow you to see the effect of using different variables—designers can use it to change individual parameters and see how the effects ripple outward and reshape whole structures. Meanwhile, in LA, Frank Gehry’s team had also begun using parametric design to bring Gehry’s strangely shaped, curvaceous buildings into being.

Eventually, Gehry technologies, with help from Mark Burry, went on to create their own parametric design software, specifically for architects, and by the early 2000s many of the most exciting new projects in architecture were being done this way. At the forefront of this was a church designed over a century ago by Antoni Gaudí: La Sagrada Família.

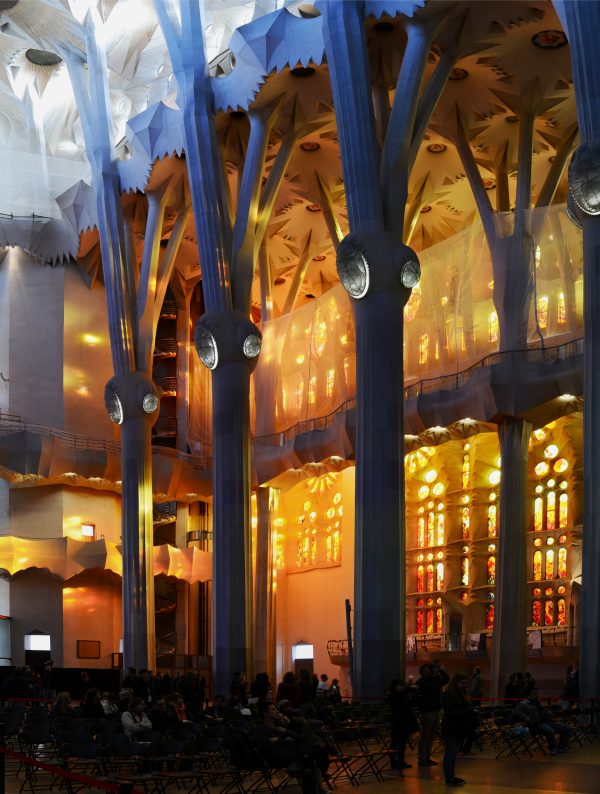

Parametric design allowed Mark Burry and the other architects to move much faster on the interior of the church. Without this technology, it’s possible there would still be no “inside” to see. It was only a few years ago, in 2010, that the architects were able to put the finishing touches on the interior.

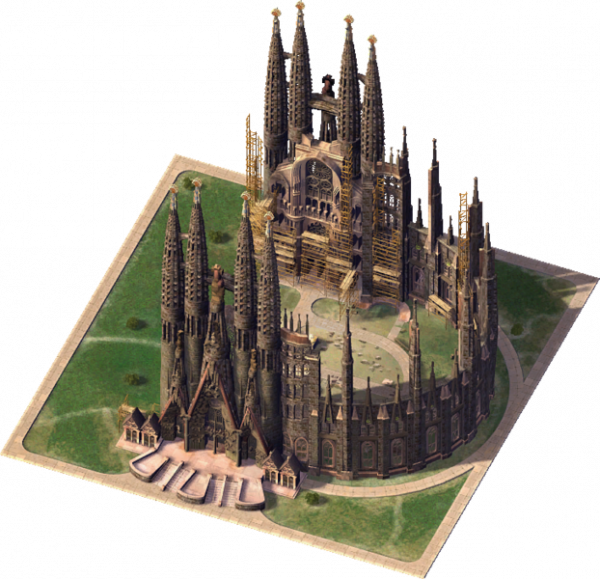

But the church still isn’t finished. There’s another huge facade to be built—the wall is there but the adorning sculptures aren’t. This one will be called the Glory Facade, and will become the main access to the church. It will depict Death, Final Judgement, and Glory (heaven).

When the building is finished, there will be 18 towers. The tallest one will be in the middle and reach to 560 feet or 170 meters.

The architects hope the building will be finished in 2026 – on the 100th anniversary of Gaudí ’s death. But there is still a lot to be done.

Comments (19)

Share

You are wonderful. I am actually sitting at a rooftop bar in Barcelona. I just watched the sunset behind Torre Agbar, with Sagrada Familia in silhouette. I am on an unexpected business trip, and your new episode is a gift. Thanks so much.

Visit Casa Batlló If you can. It’s Gaudi mind melds with Dali.

Great. I just visited Sagrada Familia last week and it was an inspiring experience. We were in the first group to visit at 9 am and stayed until around 2 pm. The play of light, color and geometry is unique and everyone who travels to Barcelona should experience it at least once. I want to see it again when it’s finished….I don’t think it will be done by 2026 though.

In the upper floor/ mezzanine of La Pedrera (in Paseo De gracia, in Barcelona) there is the Espai Gaudi a sort of Gaudi interpretation center where I could see for the first time the models you mention and the techniques Gaudi used to calculate his structures. The mezzanine itself is an example of how Gaudi built these ondulated animal like rooftops by the use of catenary arches. Its an opportunity that any architecture student shouldn’t miss.

Timing coulnd’t have been better, I’ve just booked a flight to Barcelona and found a place to stay one block away from the church. THANK YOU for this episode!

Thanks so much for the excellent podcast! I especially enjoyed geeking out to the last segment, were the modelling techniques were discussed in more detail.

If I may offer a trip down Nerd Lane of my own: I would suspect that the snail shell pictured above was used not necessarily due to the noble snail itself, but rather because of the shell shape (nautilus) and it’s correlation to Fibonacci numbers and, ultimately, the golden ratio.

Based off of Gaudi’s relationship with Nature, it’s highly likely he would have been familiar with the mathematics behind all of this, and how natural structures occur in accordance with these patterns. I would suspect that these mathematical constructs constitute at least some of the parameters that make up the foundation of the modelling that’s on going.

Looking forward to a trip to Barcelona to see this in person. Thank you again for all of the quality podcasts!

It’s not an “independence” movement, it’s secession. Catalans have been Spanish for centuries.

I’m enjoying 99pi less and less the more unnecessarily political it gets.

Rodrigo: Your practice of naive political perspective is strong. Keep it going.

Ahhhh Rodrigo, the power of the non sequitur… the Catalans are spanish, the Scots are British, the Faeroe Islanders are Danish…. What’s your point??? You could work in advertising with arguments like that.

This episode literally gave me goosebumps! Wonderfully assembled. As an emerging architect, the bit about “man does not create… he discovers” really struck me. Thanks!

I’m curious about the software mentioned in the piece. I’m guessing AutoCAD in the early nineties couldn’t handle it. Did they switch to Catia or Pro/Engineer?

One third of this episode is also about geometry and La Sagrada Familia https://relprime.com/theshapeofthings/

I’m a little bit disappointed about the incomplete picture depicted when explaining how “the conflict breaks out”.

In your version, crazy republicans run wild, burning churches until a social conflict “appears”. No mention about the progresses of the second republic, the fascist military coup of 1934 and the terrible civil war and punishment on regions like Catalunya itself during the war and the next 40 years.

I understand it’s not the topic of the episode, but I don’t think it’s very positive to equate both sides (democratically elected republic with its flaws vs. fascist military regime through a coup), especially for listeners that might not be familiar with Spanish history.

Around 4:45, the statement ‘longest-running construction project in history’ was used. I remember from some urban-development courses that Washington D.C. is an unfinished project as well. Is this distinction for ‘project’ being made for individual building?

It is the longest-running building construction project that is still going on. After all, some European cathedrals took centuries to build. Then again, those probably didn’t use the same drawings all the way throughout, as in many of them sport rather drastic style changes as the technology progressed over the years it took to build the various parts of the cathedral. The spire is usually much more modern than the crypt. The same goes for the Great Wall of China, for instance. It was worked on for some two thousand years, but without any single overarching set of blueprints, so different parts of it have very different styles.

As for urban development, that is by necessity a project that will go on forever. No city can ever be said to be “finished”. It’s not necessarily appropriate to count them on a list like this, though, since then it’s basically just ranking the oldest cities in the world.

Beautiful and fascinating episode. Well done guys.

Excellent discussion I will share people must know this fantastic history of Antoni Gaudi

wow. totally satanic look.

Loved listening to this very interesting episode and discussion. Thank you for making it.