Back in the late 1990s, NASA launched the Mars Climate Orbiter to further explore the mysteries of the red planet. The satellite cruised for close to a year, then fired its main engines to enter orbit around Mars. It disappeared behind the planet and never reappeared. The Orbiter had crashed into Mars.

Scientists at NASA began to pour over the data, looking for clues about what went wrong. They eventually discovered that a simple conversion error was to blame. NASA was using the metric system, the international standard, for its calculations. But one of their contractors was using U.S. Customary Units, which is the proper term for the American system of inches, pounds, and gallons. Years of planning and hundreds of millions of dollars were lost, all because someone did the right calculation but in the wrong units.

This was not the only time a conversion error resulted in disaster (or near disaster). In the early 1980s, an airliner ran out of fuel mid-flight after a metric conversion error and had to make an emergency landing.

This was not the only time a conversion error resulted in disaster (or near disaster). In the early 1980s, an airliner ran out of fuel mid-flight after a metric conversion error and had to make an emergency landing.

And in the early 2000s, the L.A. zoo loaned a 75-year-old Galapagos tortoise to an animal management program at a local college. The zoo warned that Clarence, the tortoise, was big and needed an enclosure for an animal weighing 250 kilograms, but the college thought they meant 250 pounds (about half Clarence’s actual weight). His first night in his new home, Clarence destroyed it.

But these kinds of failures haven’t been enough to get the U.S. to switch over to the measurement system used by the vast majority of the world. In fact, America is one of just a handful of countries that that isn’t officially metric. Instead, Americans measure things our own way, in units that are basically inscrutable to non-Americans, nearly all of whom have been brought up in an all-metric environment. Most of the world uses meters, liters, and kilograms, not yards, gallons, and pounds.

With so many industries and people crossing borders with so much fluidity, why has the U.S. not fully committed to the system the rest of the world uses? The answer is complicated.

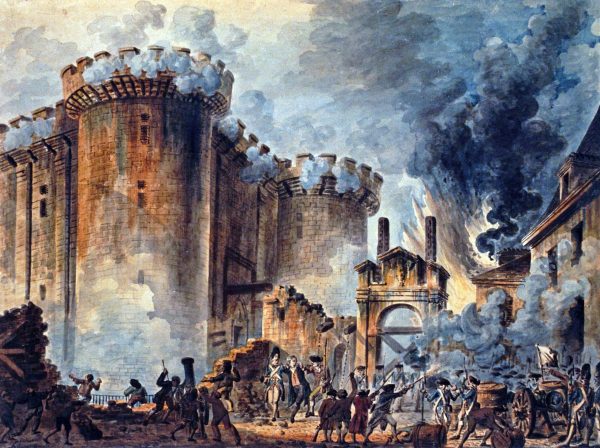

It was in the 1790s that the United States first got serious about “fulfilling the constitutional mandate to creating a uniform system of weights and measures,” explains Stephen Mihm, a history professor at the University of Georgia. “The metric system at that point was just a glimmer in the eye of some French revolutionaries.”

There was some discussion at that time, led by Thomas Jefferson, that the U.S. adopt a decimal-based system akin to the eventual metric system. But when it came time to systematize American weights and measures, inertia won out and nothing changed. The U.S. stuck with its old system of measurements, which it had inherited from the British. That system had its roots in Roman and Anglo-Saxon units that had then evolved over thousands of years before American independence.

Around the same time, French revolutionaries were heading in a new direction. They opted to throw out their old system, which they found displeasingly irrational, and to switch it for a new system — the metric system. The metric system is a decimal system, meaning it relies multiples of ten. Ten millimeters becomes one centimeter. 100 centimeters becomes one meter. And so on.

The French began promoting the system internationally, arguing that it would encourage trade and bring the world together. And it took off. By the mid-1800s, it had gained traction worldwide.

As the metric system spread, some people in the U.S., including educators and scientists, became frustrated. The metric system “lends itself really well to scientific research and inquiry, and for educators, it’s really easy to teach students and it makes a lot of sense” says Mihm.

But abandoning the U.S. customary system did not sit well with a lot of people, including and influential group of “astronomers, theologians, and cranks,” Mihm explains. “And keep in mind that those categories which we consider separate and distinct today were not at this time.” This group spun together scientific arguments with other wild and nonsensical ideas, and developed a theory that to abandon the inch was to go against God’s will. Converting to metric, they argued, would be tantamount to sacrilege.

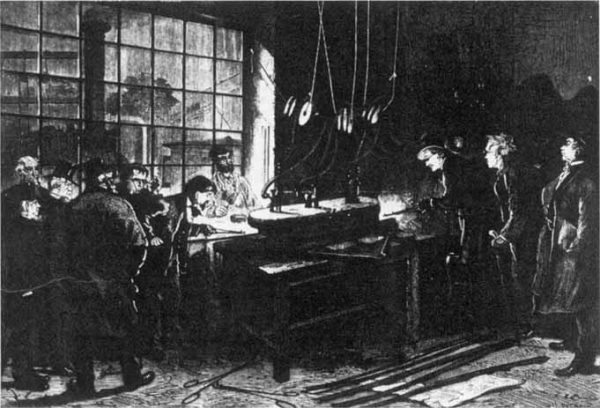

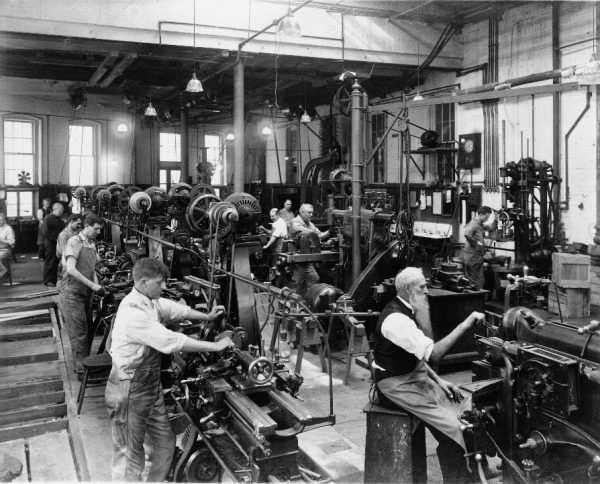

But the real core resistance to metrication came from a different group entirely: some of the most innovative industrialists of their day. Engineers who worked in the vast machine tool industry had built up enormous factories that included everything from lathes to devices for cutting screw threads — and all of these machines were designed around the inch. The manufacturers argued that retooling their machines for a new measurement system would be prohibitively expensive. They also argued there was an “intuitiveness” to the customary system that made it ideal for shop work.

Subsequent generations attempted to introduce the metric system to the U.S. but were met with subsequent generations of resistance. Congress repeatedly brought up legislation to make the metric system not just legal but mandatory — and each time time the legislation went down in flames.

But then, in the 1970s, a hundred years after the first big push for metrication, yet another attempt was made. Congress passed an act declaring the metric system “the preferred system of weights and measures for United States trade and commerce.” And President Gerald Ford followed it up with an executive order. But the adoption of the metric system was deemed voluntary.

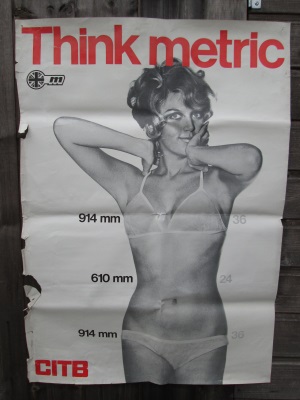

The U.S. Office of Education ran Public Service Announcements to promote metric literacy, and a popular poster was made, featuring a woman in a bikini with the slogan “Think Metric” above her and her measurements, in metric units, below.

But the 1975 Metric Conversion Act didn’t really have any teeth. It included the word “voluntary,” which meant that businesses and organizations could opt out of the metrication process. The result was that some organizations and industries went metric, while others didn’t. The metric system remained vulnerable to opposition and, once again, the anti-metric forces began to gather.

For one, there were the unions, who were scared that moving to an international system of measurement would make it easier for big corporations to ship jobs offshore.

Various writers and thinkers also rallied against the metric system — people like author Tom Wolfe and futurist Stewart Brand, the creator of the Whole Earth Catalog. In an article titled “Stopping Metric Madness!” Brand argued that: “the genius of customary measure is its highly evolved sophistication in terms of use by hand and eye…. Metric works fine on paper (and in school) where it is basically counting, but when you try to cook, carpenter, or shop with it, metric fights your hand.”

Finally, there was also a political argument against the U.S. going metric. As the Jimmy Carter era of the 1970s gave way to the Reagan era of the early 1980s, a variety of movements rose up against globalism and elitism. “This is the issue of this election,” proclaimed Reagan. “Whether we believe in our capacity for self-government or whether we abandon the American revolution and confess that a little intellectual elite in a far distant capitol can plan our lives for us better than we can plan them ourselves.” The U.S. economy was suffering and the nation’s confidence was low. As a result, anti-metric opposition began to take on a kind of defiant nationalism.

Efforts to metricate the U.S. were left stranded halfway between old and new. In a typically American way, the market decided who went metric and who didn’t and so the U.S. now sits on what’s called a “metric continuum.” The fields of science and medicine are almost fully metricated, and with little controversy. But in the business realm, it’s a mix. Some businesses are fully metricated, others not at all, and a lot are left somewhere in between.

At one end of the spectrum, there are big “companies that have international supply chains,” explains Elizabeth Gentry, the metric coordinator in the U.S. Office of Weights and Measures at the National Institute of Standards and Technology. “What they’re looking for is the ability to sell their product in many marketplaces and they get the components for their product all around the world [that] need to fit together” and create reliable products.

But for smaller, local businesses, the economic imperative to metricate just isn’t there. Take for instance a dairy farmer — milk is not shipped internationally, so retooling from gallons and quarts to liters just doesn’t seem that important.

In between, there are companies that have to maintain separate production lines, even separate warehouses in some cases, to manage different versions of their products for local and international markets.

So the U.S. is a nation stretched out across a continuum of metrication. It uses dual units and experiences conversion confusion. But it’s hard to see how that will ever change, when there’s serious cultural resistance to the system of measurement adopted around the world.

The bottom line is: it’s really difficult to get people to change from a measurement system they’ve been using their whole life. Resistance to change is a massive obstacle to overcome.

Yet what resistors don’t realize is that all U.S. customary units these days are defined relative to the metric system. The system that makes sure a gallon of gas in Oakland is the same as a gallon of gas in Omaha is calibrated relative to metric standards. So a gallon is officially defined as 3.78541 liters.

That means it’s all metric under the surface.

Comments (33)

Share

yes, the metric system would make it easier for travelers between the United States and other countries. granted it would be weird getting a 3 decimeter sandwich at Subway instead of a footlong.

but I firmly believe Fahrenheit is the better system for a layperson not working in a scientific industry. 100 is hot, 0 is cold. if its 75º F, it’s closer to 100 so it is going to be warm. dare I say we are on the right side of that one

-20ºC is cold, 0ºC is cool, 35ºC is hot, so it does not make any difference.

The only tiny problem is that nobody else uses Fahrenheit.

… hoping to hear a sister episode about why the heck America uses a different date format than everyone else.

Between you and me, the funny thing is that on the day they celebrate independence from England… they use the English format – The Fourth of July!!!

I *think* the Think Metric poster might be British from when we switched Metric in the 1960’s/70’s

It looks like it has a Union Flag in the top left and CITB is the Construction Industry Training Board, so this poster would probably have been aimed at builders in the late 1960’s or early 70’s.

Having global standards would be great, it’d make everything easier… Dates, weights, paper, cables…

Hey 99% just a thought, shouldn’t this episode have been called “Half Massed”?

As a Technology and Construction teacher it is necessary for me to teach my students inches and pounds so they can work in America. Anything is better taught with enthusiasm, so I used to go on this long tirade about how the METRIC SYSTEM IS INHUMAN and that if everyone in the classroom tried to find the halfway mark between two points (like with fractions of inches) we would be incredibly close, but if we divided it into ten sections we would utterly fail. I have never truly believed in the American system, but at the very least I figured I could get some students to.

Yet in reality all machining and manufacturing is done in decimal inches, which is a direct attempt to be metric, and every shop floor has a huge conversion chart so that workers can remember what 7/8th’s is in a decimal. In architecture and construction it takes a long time to learn how to add 3′ 4 1/2” to 9′ 6 3/4” rather than just adding 1.1m to 2.9m. Our system is a pain and switching makes sense.

After the last election I decided it is important not to teach the status quo, but what I wanted the world to become. Although I still have to teach the American system I openly admit its flaws and directly tell students that I look forward to the change in the future.

6′ 11 1/4″ while I understand your point I have worked in construction and its not the problem you think it is.

Also yes almost all critical machining is done in decimal inches I don’t buy that its a direct attempt to be metric but I see your point. Also with the conversion chart you’re probably correct but after you’ve used it for a while you just recall those things.

1/16″ is 0.0625″

1/32″ 0.3125″

1/8″ 0.125″

1/4″ 0.250″

5/16″ 0.3125″

3/8″ 0.375″

7/16″ 0.4375″

1/2″ 0.5″

9/16″ 0.5625″

3/4″ 0.75″

7/8″ 0.875″

15/16″ 0.9375″

1″ 1.000″

All that was from recall, not a chart or a calculator and I have a terrible memory in general.

However if you don’t know one but have a calculator you can just divide the numerator by the denominator and get the decimal equivalent.

Also I’d like to point that sometimes measures are given in thousandths of an inch but they are also called mils. I’ve heard people refer to thicknesses of plastic sheets as Xmm (millimeters) when in reality is was Xmils which 0.00X”. 1inch is approximately 25.4mm so a mil is about 0.0254″which means misquoting the thickness of something like this is more than an order of magnitude incorrect.

Surveryors typically use decimal feet. So they may write 1-50, usually the 50 in this example would be underlined and smaller, which means 1.5′ or 1′ 6″

Also AN fittings are interesting the sizes are a single number but are the numerator of a sixteenth fraction, so a 3AN would be for a 3/16″ nominal tube and a 4AN would be for a 1/4″ because 4/16 reduced down is a 1/4 and so on.

I also disagree with the premise that a smart intelligent society must use the metric system.

In the UK Celsius is used for weather when it is cold but people often revert to Fahrenheit when it is hot. I assume this to dramatise the extremes. By the way, you ‘pore over’ documents, etc, but ‘pour’ cold water over something.

I’m in Canada where we supposedly converted officially to metric 40 years ago but not really. We use Celsius but temperatures are also given in Fahrenheit. Grocery stores advertise food in $x/lb with $y/kg listed in microscopic print that almost no one notices.

Packaged goods are mostly sold in Imperial sizes with ridiculous metric numbers printed on them (907g of butter or 1.14L of juice) as if that’s easier to understand than 2 pounds or 1 quart.

It’s even more of a mess up here in Canada. We offically switched to metric in 1970, and it’s what I grew up learning, but because the change was relatively recent and we are inextricably linked to the US there is a wide variety in where and when it is used.

I might be 5’10” and weigh 180lb, but I’ll drive 50 km to work, fill up my car with 70 liters of gas. I’ll be happy if it’s 25 degrees C outside, but I’ll set the oven to 350 degrees farenheit. I’ll get a 4 liter jug of milk, but measure it out in cups and tablespoons if I’m cooking. Buying food can be any combination of dollars per pound, kilogram, or 100 grams. Worse yet, I work in engineering and I use both systems simultaneously, creating drawings dimensioned in mm for designed using imperials sized fasteners and structural steel.

Given that Myanmar and Liberia look like they’re adopting metric measurements, when you say “America is one of just a handful of countries that that isn’t officially metric” you must be using the imperial handful, meaning 1.

I’m sure it was an editorial choice, but paper was not mentioned. We in the US happily use Letter, Legal, Ledger, etc. The rest of the world uses A4, A3 (and no crazy Legal size).

The interesting thing here is the international angle. While it is not too bad to print a document from one format to the other (most software and printers can convert the margins pretty easily). The fun part is formatting.

The pages are just enough different in size that it throws the formatting completely off. Pictures will end up in the wrong places, page references are thrown off. The carefully crafted document with well placed paragraph and page breaks can get demolished.

Another story perhaps

The rest of the word may use A4 but you’ll still find margins are usually a suspicious 2.54cm.

Try living in the Philippines and use any conventional measuring system. Children learn both metric and non metric, but in actual practice, it remains confusing. Some refer to a 12 inch distance as a “ruler”. In fact, rulers may be metric, American standard or both. So, a “ruler” becomes a meaningless dimension.

Yeah, that poster of the girl in the bikini is British, from when we were trying to go metric. It would have been interesting to get other countries’ experiences of metrication. We (the UK) are more metric than the US, but there is still huge resistance to it. We buy milk and beer in pints, weigh ourselves in stone and pounds, measure road distances and speeds using miles. There’s a lot of identity mixed up in this I think. See the ‘metric martyr’ case of the greengrocers in the UK! And you can hear it in the show too, in the tone of voice of the pro-metric speakers. It’s clear they feel themselves superior to non-metric users!

Incidentally, the CITB, the producers of that poster still exist – http://www.citb.co.uk.

I remember hearing a story from the UK about the conversion to metric, where someone went into a hardware store to buy a 1″ screw, and was told that the store no longer sold 1″ screws. However, they would be happy to sell the person one of their large stock of 2.54cm screws. If a dairy farmer wanted to project an image of technological advance without changing their equipment, they could sell 3785mL milk jugs, and it’s not like any Americans actually need to read the label to know the volume of any of the containers milk comes in.

When I was in Canada recently, I found myself unsure how fast to drive in a 100 km/h zone. I had no problem with the conversion aspect (and my speedometer has both anyway), but my observation is that people generally drive 10 mph faster than the speed limit when the speed limit is a number of mph 50 or more; somehow, driving 100km/h+10mph doesn’t seem right, nor does picking the more common comparable US sign and driving like I would in such a zone, and 100km/h+10km/h seemed to be too slow.

I also find it really handy that distances to upcoming exits are marked in binary fractions of minutes at the speed I’m supposed to be going at. If they switched to metric, they’d probably be telling me how many centihours I have to change lanes, which is not so useful. This aspect is really that we drive 60 distances per 60*60 seconds, and 60 seconds is something everybody uses while 36 seconds is not.

On that subject, I’ve noticed that metric cooking recipes are often in weight instead of volume, which is really a more reliable way to use many ingredients anyway, but requires somewhat different technique. For that matter, my snack’s serving size is listed as “about 1/4 cup (40g)”. It’s like how American medicine dosages are reported in grams of the active ingredient, but what you get is a tablet which weighs more and you mostly think about its largest two dimensions.

On the subject of that poster, does she really have two measurements that are the same to the nearest millimeter? That’d be really implausible, even if it weren’t coincidentally within a millimeter of an even number of inches. For that matter, that measurement is a yard, but even Americans would find it crazy to say that someone is one yard around.

You erroneously biased your estimate of over speed to a round 10 mpg, when more than likely it was 20 km/h. There is a grass roots organisation in Canada to abolish to 100 km/h speed limit and increase it to 120 or 130 km/h.

http://stop100.ca/

when I was in Ontario some years ago it was common to go 130 km/h in a 100 km/h zone. That is what everyone els was doing. Here is a video showing te same thing:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=szF7dZoZKnk

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FULepxqr8tE

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=meb8pOQOQ9c

I don’t think anybody uses the full metric (SI) system in their everyday lives, we all use hours, minutes, degrees, liters and so on. The SI even “allows” the usage of those and other historically significant units (imagine speaking about angles in radians).

Also, the SI unit for time is the second, so in the “full SI world” the sign would be in hundreds of seconds, maybe kiloseconds, which would certainly be easier than centihours.

I agree about the poster though, if they were going to simply convert from inches, they should have used cm, and truncated/rounded the result.

I have a Canadian friend explaining they need to drain the pool before Winter His pool, according to him, was 5 by 8 and 5 feet deep. What? I asked why length was in metric and why dept was in feet? He did not even notice. he said his children “speak” metric, but for him, a 50+ guy, it is still a half way thing.

Why not go the full monty and go to decimal time and decimal angles and decimal days and decimal weeks and decimal months.

You can’t, however, have 10 days/week with 10 days/month with 10 months/year because that would give you 1000 days in a year and obviously that doesn’t match up real well with the seasons.

Also do a story on decimal time. After french revolution they tried to do decimal time you can even find decimal time clocks and if i recall some other people groups had some other decimal concepts of time.

Also no mention of hubble telescope? Wasn’t there an issue with it blamed on different parts from different places using different systems of measure?

I second the suggestion for decimal time! Also maybe one about the usage of base 12?

The French weren’t just making a reasoned, rational appeal to their fellow Europeans for adoption. Napoleon’s Grande Armée also had something to do with it. Subsequent colonialism by European countries also played its part.

-But abandoning the U.S. customary system did not sit well with a lot of people, including and influential group of “astronomers, theologians, and cranks,” Mihm explains.-

ASTRONOMER OR ASTROLOGIST?

My Google account is set to metric yet when I type in a location in Google maps the quick complete options are all listed with their distance away in miles “mi”. Why in such a configurable world does everyone requesting metric have to see the options in miles? Click through to get directions and they are explained in kilometres. Hmm.

Actually this is some important info you left out of EPISODE 280, ‘Half Measures’ but maybe you folks were either not born yet or were to young to know about this.

The big reason why the 1970s was the best chance for the USA to switch to the metric system was because of the Arab Oil Embargo of 1973. This caused gas prices to skyrocket. If you might remember, or seen on old-timey gas pumps (the framegrab on the YouTube video posted on the website), the digits for the fuel amount (gallons) and cost (cents) were on metal tumblers in the gas pump. Gas had NEVER been above $1 so there were only three digits (two whole numbers and tenths) for pricing. Since the entire USA could not retrofit the gas pumps overnight the solution was to sell gas by the liter. Yeah they had to write ‘Liter’ on a piece of paper to cover up the word ‘Gallons’ but it worked. They re-jigged the pumps to sell by the liter. That’s when we should have gone metric since we were already using it and wouldn’t have to redo the pumps. But alas they bought all new pumps with four tumblers and eventually that was replaced by Nixie tube digits then LCD.

I’m guessing another reason the USA is too stubborn to go to metric is because of sports. Think about the confusion and record books that would have to be changed. Football fields are 100 yards, Baseball 90 feet between bases and the Indianapolis 804.67 Kilometer auto race doesn’t exactly roll-off the tongue. Yeah, they could just refer to them anachronistically like we still can say a ‘fifth of whiskey.’ But hey, look at the bright side as we would seem to weigh less as there’s 2.2 pounds in a Kilogram and it may seem like we’re driving faster as 55mph=88.5Kmph.

Loved this episode. Hell, I love every episode. But, just came across this small clip of Trevor Noah on our ‘imperial system’ and it seems appropriate to share here:

https://www.facebook.com/GlobeEmporium/videos/1529451150408787/

The conversion from quarts to liters was incorrect in the podcast: she says “a liter is a liter bit more than a quart” as a joke but a quart is actually a little bit more than a liter. Thanks’

A “quart” is 1/4 “gallon” or 32 “ozzes” in ye olde English measure. A litre happens to convert to 33.6 ye olde “ozzes”, which is indeed “a little more than a quart”.

Sponsored in part by the Metric System, since 1799, the system trusted by 15/16ths of

I work in fasteners. Please do another episode relating this argument to bolts! We are very much NOT converted over, and our Canadian branches still use inch fasteners as well….

About very few Americans knowing whether a liter is bigger or smaller than a quart – I still strongly remember seeing a cartoon where red liquid was poured from a full liter beaker to an empty quart beaker and the liquid overflowed by a bit. (It’s in the PSA linked to in the write up, above.) I was a kid seeing that cartoon on Saturday mornings, and it really was a helpful memory device. (We were also taught how to have a general feel for the metric system in school – such as that a pencil was about 20 cm, a tall man was about 2 m, and a nice temperature as 20 – 25 C. In high school science classes, we had to memorize the exact conversion formulas for metric to and from metric. I still know these, 35 years later.)

I remember feeling in 1978 that everything would switch to metric within a few years. Reality was disappointing. (I was also disappointed that the solar panels that seemed like they would become common a few years after about 1974 also did not appear on the schedule predicted.)

The one area that I do not look forward to going metric is cooking volume measurements. That area was not covered in my school education, so seeing the metric versions of recipes always gives me a feeling a unease and discomfort. Silly, I know.

Just listened to the episode, and in the introduction you mentioned other cases where bad metric conversions lead to problems, and I thought “like the Gimli Glider”. Then you said “In the early 1980s, an airliner ran out of fuel mid-flight after a metric conversion error and had to make an emergency landing” and I was super excited, because you were talking about the Gimli Glider.

And then you just stopped talking about the Gimli Glider and moved on. “Had to make an emergency landing” is an accurate but massively understated account of the Gimli Glider story. It’s a story with all the drama and tension of the amazing ‘Structural Integrity’ episode. You should do a story on it!