The Orange County courthouse in Santa Ana, California is a large granite and sandstone building from the early 20th century. There, Jennifer Birch was there doing research for a group called Moms Demand Action. It’s an organization that advocates for gun control and regulation. Moms Demand Action had dispatched volunteers like Jennifer to courthouse basements and local archives all over the country to dig up some of the oldest, most overlooked gun laws in the nation’s history. And their goal, ultimately, was to fact check the highest court in the nation.

What Moms Demand Action discovered is one of the biggest gun cases in American history was decided based on questionable data. But it turns out this problem is bigger than one case, and it’s bigger than Moms Demand Action. The Supreme Court has a long relationship with bad facts. In 2017, ProPublica analyzed recent Supreme Court cases for factual errors. In total, ProPublica found seven Supreme Court decisions, just in recent years, where the Justices got their facts wrong.

Sometimes these mistakes didn’t have much impact on the decision itself…but sometimes they do. Sometimes Justices hinge their decision on these facts. So how is it that the highest court in the nation can get their facts wrong not once, but again and again and again. And what even happens when you prove them wrong?

Credit: Fred Schilling, Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

Formalists vs. Realists

For a long time, the Court operated under what was called Legal Formalism. Legal formalism said that the job of any judge or justice was incredibly narrow. It was to basically look at the question and the question of the case in front of them, check that question against any existing laws, and then make a decision. Unlike today, no one was going out of their way to hear what economists or sociologists or historians thought. Judges were just sticking to law books. The rationale for this way of judging was that if you always and only look at clean, dry law the decisions would be completely objective.

In the late 19th, early 20th century a movement rose up to challenge legal formalism. They called themselves the legal realists. Fred Schauer, professor of law at University of Virginia. says the Realists felt that the justices weren’t actually as objective as they said they were. “Supreme Court justices were often making decisions based on their own political views, their own economic views, and would disguise it in the language of precedence or earlier decisions,” says Schauer. The realists said lets just accept that reality and wanted to arm the judges with more information so those judges could make more informed decisions.

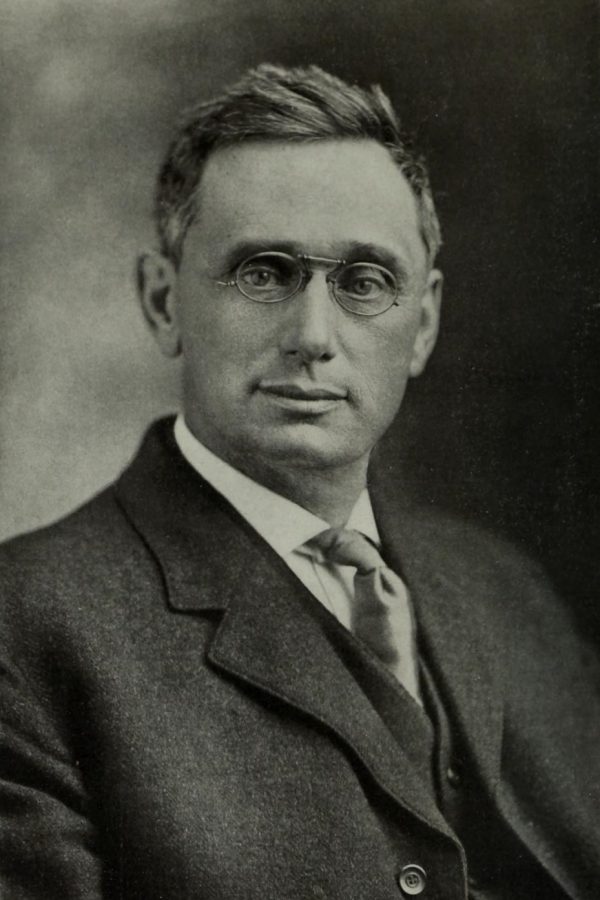

For a long time the debate between realists and formalists had been mostly theoretical. That is until the arrival of the Brandeis Brief. The Brandeis brief came during a pivotal court case in the early 20th century. And the man at the center of that case was a legal realist and progressive reformer named Louis Brandeis.

The Peoples’ Attorney

As a young, zealous lawyer, Brandeis fought against the biggest railway monopoly to keep the Boston Common as a space for the people. He fought for better life insurance for all Americans. And then, In 1907, Brandeis set in motion a shift that would… for better and worse… change the inner workings of the highest court in the nation.

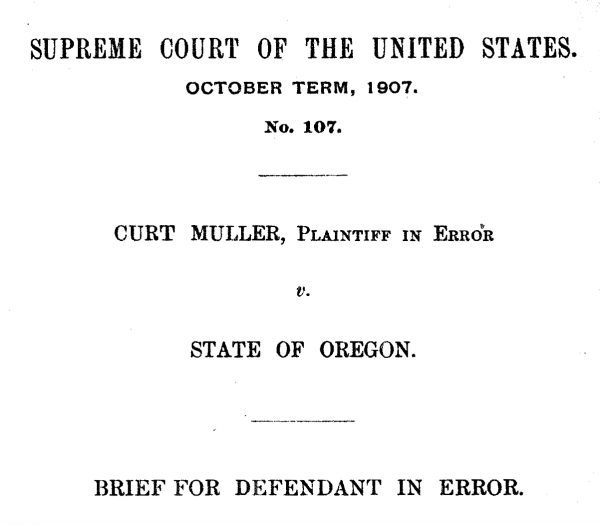

It all started when he agreed to argue a labor case in front of the Supreme Court. As part of arguing the case, lawyers on both sides submitted their briefs. No facts about the real world. But rather than writing the typical brief, Brandeis went a completely different direction. Instead of just including the basic, dry legal precedent, he filled his brief with over 100 pages of facts that he thought should be present in the courtroom. In his brief, Brandeis included scientific facts about how women needed special protection from long working hours. He included medical reports, statistics, psychology studies, all showing that long working hours affected the “the health, safety, morals, and general welfare of women.”

Many of those facts have actually been debunked, but Brandeis was the first lawyer to go before the Supreme Court to ask the justices to understand facts about how the world works to make better legal decisions. Brandeis took a risk in submitting the brief, and it paid off. The Justices read the brief and all the information he had provided, and they ruled in the women’s favor.

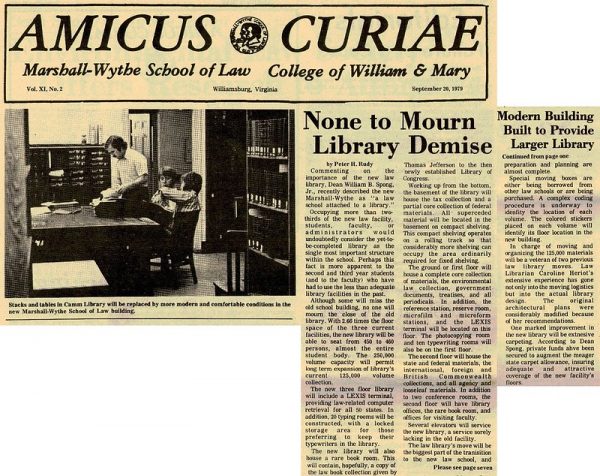

The Amicus Brief

Before this point even Legal Realists wouldn’t have written briefs that the Justices might just ignore. But now they basically had a stamp of approval. That stamp only became more official when Louis Brandeis himself was appointed to the Supreme Court eight years later. Over the next few decades, Legal Realism completely transformed the court’s landscape. Not only did it change the way lawyers worked, it changed the way judges worked too. Judges and justices started taking it upon themselves to read books and articles – related to cases they were in the process of deciding. Which today seems obvious, but this was all new territory.

In a way, it does make sense to bring the Justices down to earth from their high minded, lofty legal theories. The Realists thought they’d created a world where Judges would learn the real facts on the ground, and make better legal decisions because of it. But when the rubber hit the road, things went a lot differently than they imagined. But the Brandeis brief was at its core a tool. But progressives weren’t the only group who could wield it. While the reformers were out celebrating wins like Brown v Board and Roe v Wade they had set in motion a change that would eventually derail some of their biggest wins, and at the center of that change was that thing was called an amicus curiae brief – or “amicus brief” for short.

These are briefs that are typically written by people or organizations who don’t have any role to play in the case. They’re not lawyers for either side. They just have an opinion about how the judges should rule and why. So they write an amicus brief saying how they think the case should go. The idea is that they give perspective, research or context about an upcoming case. Unlike regular briefs, where the lawyers in the case write in, these are written by people outside the case. Any member of the public, or any organization, can submit these briefs. In a way, amicus briefs are exactly what Legal Realists like Brandeis wanted. They’re a means of getting information from the real world into the courtroom.

The Real World Enters the Court

Amicus briefs flowed into all the big cases of the 20th century: Roe v. Wade, Bush v. Gore. And over the decades, they slowly became a fixture of the courtroom. In 2003 came a case that pushed the amicus brief past its humble origins, and into the spotlight. The case was a challenge to affirmative action at the University of Michigan. When Justice O’Connor delivered her opinion in the case, explaining why the court sided the way it did, she mentioned one specific amicus brief that the court had received. For the first time, Justices were showing that not only do they read these briefs, amicus briefs actually play a big role in helping them make decisions. When Justice O’Connor referenced specific amicus briefs in an official court decision, it sent a clear message that if your side sends in the right amicus brief, that could decide the case.

But the dirty secret was that the Supreme Court doesn’t have any fact checking mechanism for amicus briefs. In fact, there’s no fact checking for anything that the judges read to decide their cases.

The situation today is, if possible, even worse. Because we’re not just dealing with the issue of what is in the briefs.

Now, we have a certified Amicus Brief Industrial Complex. Lawyers today don’t just wait for experts supporting their views to weigh in. They actively reach out to the people or interest groups they want to write in. And they’ll dictate what, precisely, they want those amicus briefs to say. Hundreds of these amicus briefs flood into the hands of law clerks who have no capacity and no system for fact-checking. And that is the information that the Supreme Court uses to make its decisions.

The result of the amicus brief industrial complex is that in the worst case scenario, the side with more money can drum up more amicus briefs, and that gives them a huge advantage. And even in the best case scenario, there’s essentially an information deadlock. The Court has a ton of very convenient facts from both sides, and in the end it’s up to the Justices and their chosen clerks to decide which facts to actually believe.

Leave a Comment

Share