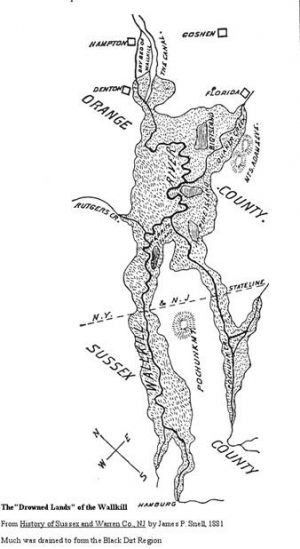

Pine Island seems like a strange name for a New York hamlet entirely surrounded by dry land. Historically, though, it was a seasonal islet — a high point in the region defined by the regular spring flooding of the Wallkill River. The Wallkill flows from New Jersey into New York, spanning an area once called the Drowned Lands, disputed semi-aquatic territories at the heart of a strange intergenerational conflict that pitted millers against farmers, or: beavers against muskrats.

As early Dutch settlers made their way up the Wallkill, they found that the valley flooded extensively to form a huge lake in the spring. Many would use the land for cattle pastures, a practice that came with risks. Landowners would “rent out pasturage to the cows of neighboring farmers,” according to local historian James P. Snell’s account in 1881. “Through the summer season, thousands of cows were turned upon the waste acres. Sudden freshets frequently came and the water rose so rapidly that many cattle were annually lost before the herdsmen.”

Unable to graze cattle safely or plant crops in the floodplains, some locals began to see an opportunity to create more stable and productive farmland. As far back as the mid-1700s, efforts were made to rationalize and systematize the landscape, dredging and draining the river. Not everyone was on board, though. Lumbermen and mill owners enjoyed the freedom to chop down trees and float lumber down the river unimpeded to points closer to New York City, from which milled lumber could be shipped on by rail. Some factories along the river also relied on the water power it provided. In short, industry needed the water to flow while agriculture needed it to be diverted.

Early attempts by farmers to control the river were ineffective, but things started to heat up when a “Board of Drowned Land Commissioners” was created by landowners in 1807. At its head, farmer George Wickham advocated the dredging of a canal through his own property that would drain the whole area. It would take decades of lobbying, but eventually, he secured state funding, contingent on a majority of Drowned Lands owners approving the plan in 1829.

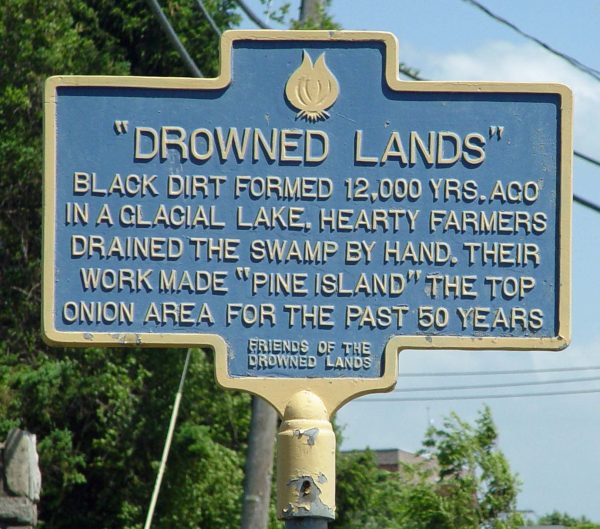

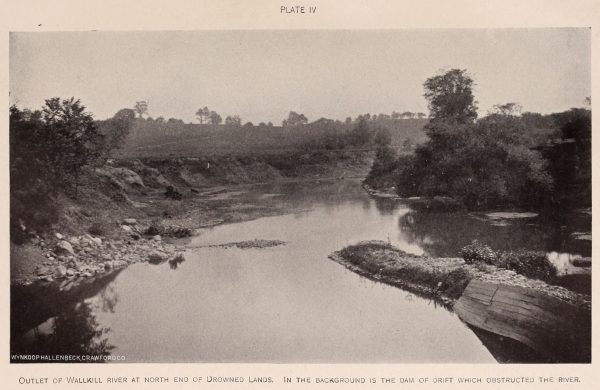

The vote itself was close and contested, to the point that each side claimed victory and accused the other of malfeasance. The farmers prevailed, however, and a canal was dug, sparking what became known as the Muskrat and Beaver War. Lumbermen and mill owners (“beavers”) began damming the canal while farmers (“muskrats”) continued to destroy their creations. Things escalated. At times, large groups of armed men on both sides would gather to protect or destroy dams. As activists engaged in various illegal activities, warrants were issues and injunctions sought on both sides. The “war” went on for decades, finally settled in 1871 by a judge who outlawed any further dam-building efforts. In the end, the farmers prevailed and the area has become known as the Black Dirt Region, famous for its rich soil, but the victory came with side effects — nature is not so easily bested. As time went by, the initially narrow 12-foot canal naturally grew wider, washing away infrastructure on both sides and widening up to 700 feet across in places. In the process, a lot of farmland was washed away, too.

The vote itself was close and contested, to the point that each side claimed victory and accused the other of malfeasance. The farmers prevailed, however, and a canal was dug, sparking what became known as the Muskrat and Beaver War. Lumbermen and mill owners (“beavers”) began damming the canal while farmers (“muskrats”) continued to destroy their creations. Things escalated. At times, large groups of armed men on both sides would gather to protect or destroy dams. As activists engaged in various illegal activities, warrants were issues and injunctions sought on both sides. The “war” went on for decades, finally settled in 1871 by a judge who outlawed any further dam-building efforts. In the end, the farmers prevailed and the area has become known as the Black Dirt Region, famous for its rich soil, but the victory came with side effects — nature is not so easily bested. As time went by, the initially narrow 12-foot canal naturally grew wider, washing away infrastructure on both sides and widening up to 700 feet across in places. In the process, a lot of farmland was washed away, too.

Finally, in the 1930s, the US Army Corps of Engineers stepped in to try and stabilize the increasingly out-of-control river. These days, there are still farms and mills in the area, but other forces as well — encroaching suburbs and wildlife refuges among them.

Some local places with “island” in their name remain as reminders, recalling a landscape that led to a long and strange conflict. For those interested in diving deeper into this muddy regional history, James Snell’s full account of the Beaver and Muskrat War is a fascinating read.

Comments (1)

Share

This makes me think of the not-entirely-unrelated draining of the once mighty Tulare Lake in California, and subsequent acquisition of Federal flood control dollars, as told in “The King of California”.