Today, Berlin is one of the premier destinations for techno music fans. People come from all over the world to party all night to the rhythmic beat of Berlin’s club scene. And this music that the city is most famous for developed in large part because of the thing the city is most infamous for: the Berlin wall, which divided the city into east and west for almost thirty years.

The East and West inside the East

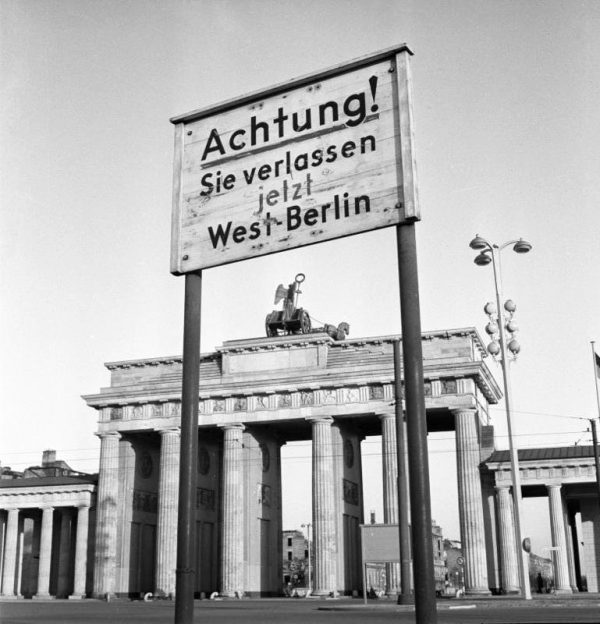

Germany was divided into East and West at the end of World War II—and so was the city of Berlin. East Berlin was socialist and controlled by the Soviet Union. West Berlin, on the other hand, was capitalist. It was a strange island outpost of democratic West Germany, completely surrounded on all sides by socialist East Germany. In 1961, the city became divided not only politically but physically as well. The East German government built a huge wall, with checkpoints, to prevent its citizens from fleeing to the west.

And soon, divided by a wall and living under completely different political and economic systems, two distinct cities emerged. Each had its own unique cultures and music scenes.

For most West Germans, West Berlin was not considered an attractive place to live. There was hardly any industry and you were essentially cut off from the rest of West Germany, surrounded by a wall on all sides. And so eager to attract people to the city, the West-German government dangled a few incentives to get people to move there.

Rent was incredibly cheap in West Germany, and anyone who moved there was exempt from the otherwise mandatory military service. All this all made West Berlin a haven for misfits, hippies, queer people, and artists of all kinds. “So anybody who was kind of weird, or just generally weird, or didn’t fit into what was perceived as ‘West German’ society… you went to Berlin and you met everybody who was just like you,” explains Mark Reeder.

A Proper Scene

West Berlin hadn’t really been known as a musical city, it was known for its wall, and its Cold War politics. But by the early 80s, with these new arrivals, an eclectic scene started to develop. Clubs and bars started to open and soon, on any given night, you could hear disco or hip-hop or new wave music. There was also an experimental rock scene, full of a constantly changing line-up of bands.

But while people like Reeder were having all kinds of parties in West Berlin, just behind the wall in East Berlin it was a completely different world. In socialist East Germany, music was viewed as a potential danger to the state and was heavily regulated. The only publisher of music was the government-run label and they didn’t allow anything subversive.

If you wanted to be a DJ, you had to be officially trained and licensed by the state. The same was true if you wanted to own an electric guitar or perform in a band. You also couldn’t just hold a dance party—that also needed to be approved by the state. First, you’d have to explain to the powers-that-be exactly what you would be doing and what political and cultural goals you hoped to achieve.

The application would wind its way through official channels and, often months later, you’d be approved to host one of these dances. Everything in East Germany took its time. So there were two different Berlins: West and East, meters apart but inhabiting starkly different realities both musically and culturally. But while they couldn’t take part in West Berlin’s club and music scenes, many East Berliners knew about it because they could pick up the West Berlin radio stations which beamed over the wall.

Ich Bin Ein Berliner

Beginning in the mid-1980s, Mikhail Gorbachev became the new leader of the Soviet Union. Gorbachev favored an approach called “glasnost,” the Russian word for “openness.” He was much less authoritarian than earlier leaders, and he started allowing for more transparency and dissent. In the space of a year or two, many people had lost their fear of speaking and acting freely.

At first, the ruling Soviet-aligned East-German socialists didn’t share Gorbachev’s enthusiasm for openness. They were in no rush to follow his example. But as the 80s dragged on, the East-German government was being put under more and more pressure by its own citizens to make similar changes. By the fall of 1989, there were increasingly large public demonstrations taking place, something that until recently would have been unthinkable. There was a growing sense among citizens that they might be able to actually change things.

When the Berlin wall fell in November 1989, Wolle Neugebauer says it still came as a complete and utter shock. He says he can still remember the night very clearly. He and his girlfriend had been out at a party when they decided to call it a night. When they got home, he turned on the television and they saw the news. What they learned was that the East-German border guards became overwhelmed by huge crowds that had gathered at the border crossings and were simply letting people through to West- Berlin. Suddenly there were no more controls. So they decided to go to West Berlin.

To the Clubs!

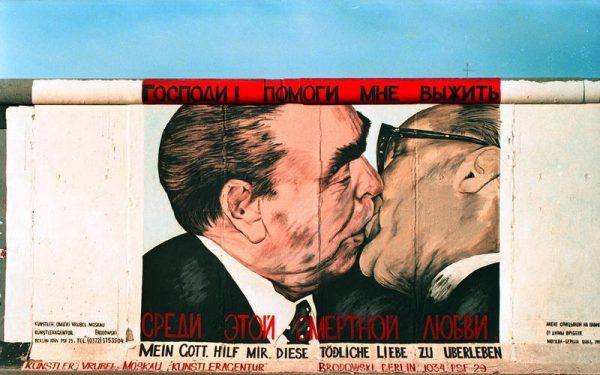

In the days and weeks that followed, everyone was euphoric and parties started popping up everywhere. “Right after the fall of the wall, it was like the first thing that people wanted to do is go out clubbing,” says Mark Reeder, “For the first time these kids in the East had the opportunity to choose what kind of music they wanted to listen to. It wasn’t music dictated to them by the state of East Germany.”

And the fall of the wall happened to occur at a moment when music was going in a brand new direction. The acid-house scene of Berlin was quickly moving towards what’s known as techno, a darker, more propulsive style of music created by Black electronic musicians in Detroit. The harder Detroit sound had a huge influence on European musicians, especially the Germans.

A whole political system had just crumbled, the future felt unwritten, and this new Techno music fit that sense of newness perfectly. But these techno parties were still relatively small. UFO, the main West-Berlin basement club where this new music was being played, was tiny. It couldn’t hold more than 100 people at a time.

Wolle Neugebauer wanted to organize something bigger. Freed from the restrictions of the East German state, he wanted to throw huge parties with fog machines, and strobe lights, and techno music that would play all night. He called these parties Tekknozid parties. And as anyone who was there will tell you, it was on the dance floor that East and West really came together. “The unification of Germany happened on the dance floor. It didn’t happen in politics until much later,” says Reeder.

As the techno scene exploded, party organizers faced a problem. They needed bigger and bigger venues to accommodate the growing crowds. Unlike West Berlin which was cramped and claustrophobic, East Berlin had plenty of space. Der Spiegel journalist, Tobias Rapp, was a teenager from West Germany who had just graduated high school when he decided to move with a friend to East Berlin just a few months after the wall fell. They quickly found an entire apartment building to squat in. For Tobias, the whole city was like a big playground of derelict buildings. It wasn’t just the abandoned apartments. There were also former military sites and factories that had been shut down and buildings that had been condemned.

Not only were there tons of empty buildings, but it also wasn’t even clear who owned them. Decades before, the Nazis had seized property from Jewish citizens, and after the war, the communists took away real estate from who they perceived as Nazis or the bourgeois class. What property belonged to whom was a very murky question that would take years to sort out.

The Vault

And while this chaos over ownership was a headache for the state and, of course, for the descendants of the people whose property had been seized, it was a godsend for the newly emerging techno scene. With the huge amount of abandoned space, parties started emerging everywhere, usually just for a night or two, and then moving on to somewhere else. The parties were always changing locations and Berlin’s underground techno scene might have eventually faded away were it not for a guy named Dimitri Hegemann.

Hegemann helped turn the city’s chaotic underground techno movement into a permanent club scene that would change the landscape, and economy, of Berlin entirely. He was a West-Berliner, and it was his tiny illegal basement club — the UFO Club — that had been at the center of the small club scene in West Berlin. But now that the wall had come down, and the techno scene was expanding, he wanted something bigger.

One day, in 1990, Hegemann was stuck in a traffic jam with two friends right by the former wall when they noticed a large concrete building that was at one point a department store. They ventured down into the building and found an enormous vault which they were able to rent on a three-month lease. They spent the next few months cleaning it up. And in March 1991, they opened up a club. And called it Tresor, the German word for “vault.” Now you didn’t have to call a secret number to find a techno party, now on a Saturday night, you knew exactly where to go. The scene was evolving from fleeting parties in scattered places to something bigger and more established. Tresor quickly became known for its hard Detroit-inspired techno parties that would go all weekend. With the fog machines and strobe lights and loud beats, people seemed to forget time and space.

Tresor didn’t just help popularize this new harder Detroit techno sound, it also helped build a real connection between the Berlin and Detroit techno scenes. Dimitri started the Tresor label and began releasing the work of many of these Detroit musicians throughout Europe. Tresor’s three-month lease was extended for another three months. And then another. And meanwhile, a whole network of clubs began to develop nearby, in the empty buildings right by the former site of the Berlin wall. Over time, the techno scene began driving an economic revival in Berlin.

Built on Techno

People began opening not only clubs, but bars and art galleries and all kinds of small businesses, and all these new businesses could basically fly under the radar. There was so much else going on with the politics of reunifying the city, that for the most part, no one was really checking to make sure anyone was paying taxes, or acquiring the proper permits to put on events or serve alcohol which was the case for years.

In many ways, Berlin hadn’t had a stable identity since World War Two. The city had been occupied, then divided, and never had much of an industry. Plus the shadow of being the capital of Nazi Germany still lingered. But the new culture that started to grow up around the techno scene helped to change that. And as techno migrated from the underground to the mainstream, it began to draw people from all over the world.

Word had gotten out: if you like techno and nightlife, you’ve got to check out Berlin. Over time, some of those travelers decided to stay. And with all the new energy, the nightlife became a real economic force. In 2018 the techno scene helped generate 1.4 billion euros for Berlin. Today the techno scene is so important economically to the city, that even the conservative Christian Democratic party of Berlin talks about the need to support Berlin’s club culture, despite all the drugs and hedonism that it involves.

It wasn’t just the direct impact of the club scene that was changing the city. There were lots of knock-on effects as well. Tech companies related to electronic music, like Soundcloud, Ableton, and Native Instruments were founded in Berlin. Berlin was growing faster than the rest of Germany. And for Hegemann and others involved in the early scene, much of the credit goes to Techno. “I think the influence of techno music and the subcultural nightlife that comes along with it on the development of the city is much much bigger than anybody imagined,” says Tobias Rapp.

Comments (6)

Share

Who would’ve thought 99pi would become a platform for trite Cold War propaganda of Eastern Bloc = bad, Western Bloc = free. Goodbye 99pi, who taught us to look at the built world in a completely new light and with this episode failed to live up to your own standards.

I mean….they just stated facts within the contextualized subject? Is there a different universe where people had musical and artistic freedom on the Eastern Bloc that we’re missing? Or was experimental music and dance clubs totally cool and legal over on EB because I’d love to learn more!

“Rent was incredibly cheap in West Germany, and anyone who moved there was exempt from the otherwise mandatory military service. ”

This sentence is (well, should be) about West BERLIN, not about West GERMANY.

And while Love Parades started in Berlin, the photograph shows a float from Tunnel club in Hamburg,

I’m actually living the outros being different every time. Low-key hope they never give you the real thing

Thank you so much for this piece! I developed a deep love for techno in the mid-90’s and was drawn to the Detroit and Berlin sounds stronger than anything else. I was inspired to become a DJ myself as I was finishing high school, and collected soooo many records, a significant portion of them being on the Tresor label. When I finished college, I made Berlin a priority stop in my obligatory post-graduation backpacking trip. I knew there was a Tresor club, and the workers at the hostel I was staying at knew exactly where it was. So on Saturday night, I stashed my belongings in a closet at the hostel, made my way downtown, and stepped into a space I had only imagined. It. Was. Wild. My most vivid memory is from the vault (which I had no idea was part of the club until I discovered it whilst wandering around). There was one chaser strobe on the ceiling providing the only light. It was as minimal as the music, and I loved it all.

I have always appreciated the way 99PI sheds light on things that could easily go unnoticed. I knew a fair amount of what was included in this piece, more than usual, but the parts that were new to me were fascinating!

Thanks again for the story. I was inspired to write a short story about my adventure, something I haven’t done for years. It was fun!

Hor Berlin /the Boiler Room have been my pandemic project. Good to hear about some context.