One of the cool parts about moving to a new city or a new state or a new country is that you notice all the fascinating things about a place that is just normal for people who have been there for a long time. When Chris Carlier moved from England to Japan in 2002, there was one thing that he couldn’t help but notice: the mascots. (Update: the 99pi store now has masks featuring Amabié, the legendary yokai!)

In the US, mascots are used to pump up crowds at sporting events, or for traumatizing generations of children at Chuck E. Cheese, but in Japan it’s different. There are mascots for towns, aquariums, dentists’ offices, even prisons. There are mascots in cities that tell people not to litter or remind them to be quiet on the train. Everything has a mascot and anything can be a mascot. As Chris Carlier adjusted to his new life in Tokyo, he started snapping photos of all these mascots he was coming across, and Carlier’s hobby has since morphed into a wildly popular twitter account called Mondo Mascots.

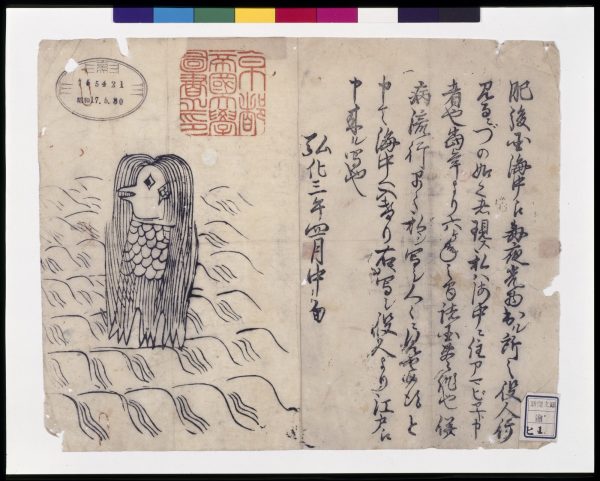

Usually, these costumed mascots are out interacting with the world, waving to tourists or opening supermarkets — but like the rest of us, they’ve recently had to spend a lot of time indoors. One mascot was making quarantine workout videos for people stuck at home; another posted photo after photo of himself just staring blankly into space. Around mid-March, there was something kind of odd and very meta happening on the Mondo Mascots twitter feed. Some of the more well-known mascots were adding all these new flourishes on top of the regular mascot costumes. They were all wearing long, flowing blue wigs, colorful fish scales, and a beak. It was like all these different mascots were channeling the same mythical character. It was a mythical character called Amabié: a 174-year-old creature that has recently become the unexpected hero of the COVID era in Japan.

A Talisman Against Plague

Throughout the 19th century, cholera epidemics were sweeping the world, and Japan was hit especially hard. Wave after wave of outbreaks devastated the country over the course of several decades. At the time, very little was known about the disease and how to fight it.

According to a news story of the era, Amabié was spotted off the coast of Southwestern Japan in 1846. For several nights in a row, villagers could see a mysterious light radiating off the coast towards the sea. One night, an officer was sent to investigate the source. He followed the light toward the water until he was greeted by a strange looking creature who appeared out of the sea. It had the beak of a bird, long locks of human-like hair, a body covered in scales, and three legs with webbed feet. The creature said its name was Amabié. It predicted a bountiful harvest for the next six years and told the officer that if plague should ever ravage these lands again, show an image of it to the people and it would protect them from harm. The story of Amabié was written in a newspaper of the time and nearly forgotten.

In February of 2020, Amabié’s story emerged again when a Japanese artist tweeted his own rendition of Amabié calling it a “new coronavirus countermeasure.” Since then, Amabié has gone viral, with thousands of people posting their own artwork of Amabié, hoping it will protect the world from the virus.

Superstitions With Personalities

Amabié is a creature from Japanese legend — what’s called a yokai. “Yokai are monsters from Japanese folklore,” explains Matt Alt, “and they’ve been part of the oral storytelling tradition here in Japan since before Japan has been Japan … they’re basically like superstitions with personalities.” Alt is a writer based in Tokyo and co-author of the book Yokai Attack! The Japanese Monster Survival Guide. Such figures “are characterizations of natural phenomena or unexplained phenomena,” elaborates the book’s co-author, Hiroko Yoda.

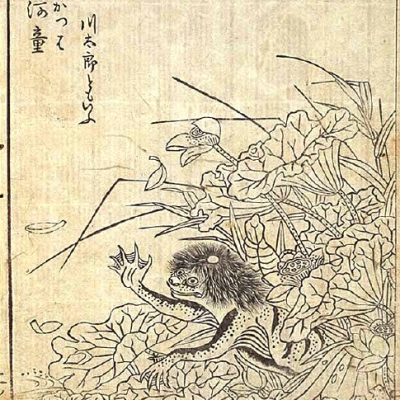

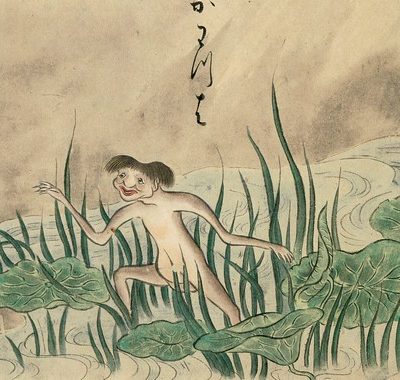

Yokai is a pretty broad term that includes everything from shape-shifting demons to cuddly animal-like creatures as well as spirited inanimate objects and ghosts. But mostly, yokai are supernatural manifestations of the unknown. If you don’t have a way to explain an unexplainable phenomenon, you can blame it on a yokai. Occasionally they take the form of benevolent “guardian angels”, but while some yokai are completely innocuous, more often than not they’re malevolent beings associated with a specific place— like regional ghosts or the troll that lives under a particular bridge.

Everything is Alive

The first yokai stories were told in the 8th century, but you can see the traces of yokai that stem thousands of years back to Japan’s native religion of Shintoism. Shinto is so tightly woven into the fabric of Japanese society that it’s difficult to separate where the religion ends and Japanese culture begins. “Modern-day Japanese people [don’t] realize Shinto is our culture’s basis,” explains Izumi Hasegawa, head priest at Shinto Shrine of Shusse Inari in America. For Hasegawa, it is in fact “not a religion” but rather “more like a way of living — culture, tradition, custom,” a belief system that venerates millions of deities called kami that live all around us and impact daily life. Kami reside within everything … the trees and the wind, even your iPhone. “You have this belief system in which nearly anything can be a receptacle for a deity or a soul. And many of those kami are actually personifications,” says Matt Alt, “That world view … that belief system of polytheism and animism is the soil from which yokai emerged.”

An Encyclopedia of Yokai

In the beginning, tales of “spirit monsters” varied drastically from region to region and were passed on as verbal stories with no real visual form attached. A kappa water goblin from the south might be described totally differently from a kappa from the north. That all changed during the Edo Period which took place between 1603-1868. This period was a time of political stability and economic growth for Japan, during which the publishing industry started really taking off, and books became the primary sources of entertainment.

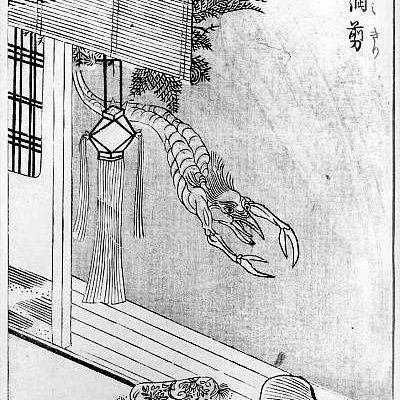

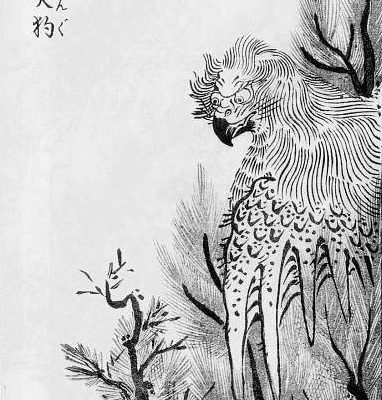

One of the most popular types of books was the encyclopedia, and in 1776 an artist named Toriyama Sekien illustrated and published his own version of an encyclopedia filled with different yokai called The Illustrated Night Parade of a Hundred Demons. This was an important moment for yokai as a folkloric tradition because up until this point, these stories had been mostly told orally and varied widely from region to region. When Sekien created his encyclopedia of yokai, it codified what these monsters looked like in Japan’s national imagination and yokai became a part of pop culture. “He was the first person to really start putting images to these fairy tales and superstitions and folklore creatures that had only been talked about up until that point,” says Alt, “And when that book became a surprise bestseller, it essentially cemented the image of a lot of yokai in place.”

In part because of Sekien’s encyclopedia, stories about yokai flourished during the Edo Period, both as entertainment and as a way of explaining the many unknowns of the world. In lieu of scientific information, yokai could be seen as the cause of unexplainable phenomenon. As Hiroko Yoda explains, “Today, we have science to explain [things like a] plague,” but at the time, there wasn’t much medical information, so yokai played an explanatory role instead.

The Ghostbuster

Mythical creatures like Amabié played an important societal role within Japan in the 1800s. But by the turn of the 20th century, Japan’s relationship with its Yokai began to shift because of a man named Inoue Enryo. Inoue was an academic and philosopher who didn’t find comfort in yokai at all and actually made it his mission to displace them from the Japanese psyche for good.

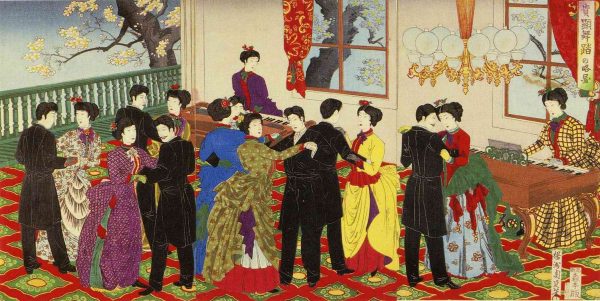

Inoue was born towards the end of the Edo Period right as Japan was going through a transition called the Meiji Restoration. For hundreds of years, Japan had isolated itself from the rest of the world, but as the country began opening up, leaders wanted to compete with Western countries in terms of science, technology, and military power. Inoue saw yokai and other superstition as a crutch holding back the nation. If Japan was going to become a world power, it needed to actively embrace modernity. He felt that so as long as people clung to superstition to explain away the unknown, Japan would never reach its full potential. He ended up traveling around the country debunking yokai stories and urban legends.

Inoue became a sort of ghostbuster. He created his own area of research called “Yokaigaku” or “Yokai Studies” and used scientific experimentation to explain away the phenomena that yokai were previously attributed to. But it didn’t just stop at yokai — a lot of local customs and traditions were quashed during this time. “I think that movement went too far,” says Hiroko Yoda. “Our local beliefs [were] totally killed by modernization.” And even though Inoue earned the reputation as a debunker, it’s actually thanks to him that we know as much as we do about yokai. Inoue was an incredibly thorough researcher and kept meticulous notes. His work has been really helpful for people who study folklore.

Inoue didn’t necessarily reject all mystery — in fact, he was fascinated by the great mysteries of life, what he called “true mysteries.” True mysteries were the absolute unknowable things that humans can never be explained no matter how much we learn, like the secrets at the core of human existence. But he was a Buddhist and a scholar, and just didn’t think stories about monsters fell into that category. “He didn’t deny all possibilities of mystery,” says Michael Dylan Foster, professor of Japanese at UC Davis, but did believe “most of the mysteries that we see — most of the Yokai — can be explained away. But there are those that can’t be explained away and those are what we have to find.”

Out of the Shadows Again

For years yokai existed in this nebulous space. Their stories weren’t entirely forgotten, but they were suppressed in the name of rationality and progress. It wasn’t until after WWII that yokai crept out of the shadows and back into the public imagination again. In postwar Japan, when the country was recovering from the war, manga and cheap comic books became an increasingly popular form of entertainment. Mizuki Shigeru was an artist and animator who was also a folklorist with a strong affinity for yokai. In 1960 Mizuki created a manga series called Kitarō of the Graveyard which was eventually turned into a hugely popular animated series called GeGeGe no Kitarō.

The plot centers around a young ghost boy named Kitarō who keeps the peace between the world of yokai and the world of mortals and his companions are all different yokai. Mizuki used this series as a platform to propel yokai back into the Japanese mainstream. “When I was a kid, I saw the animation and I grew up with it. It was huge and popular,” remembers Hiroko Yoda. “Many of the yokai are based on the old yokai—he brought them back.”

Mascots for a Bygone Era

Since Mizuki’s reintroduction, yokai have been a constant presence in Japanese pop culture. There has been reboot after reboot of Kitaro over the decades, as well as incredibly popular franchises like Yokai Watch which is introducing newer generations to yokai. And these monsters are all over the cultural exports that people in the West love. You can see the dark whimsical undercurrents of yokai in the work of Haruki Murakami, or the animation of Hayao Miyazaki, even Pokemon!

Japan can sometimes seem to have a reputation as a place filled with many odd and original characters, but Matt Alt believes that once you take the time to trace its history, it doesn’t seem odd at all. “A lot of times foreigners come here and they see this and they’re just blown away by the sheer amount of super cute characters running around on the streets of Japan … and then they mistake it for it being kind of infantile or childish. But in reality, the roots of that character and mascot culture can be found in the yokai who are sort of mascots for a bygone era.”

Mizuki Shigeru, the man who revived yokai in the 20th century, was concerned about whether there was enough room for yokai in modern society. They’re products of an older era — one that relied on faith and superstition rather than science and technology, and so one would think that the more we learn, the less space there is for yokai. But Michael Dylan Foster doesn’t think that’s the case. Foster says that yokai have been a part of popular imagination, and will remain a part of popular imagination in one form or another. “The need for explaining mystery never disappears once we scientifically explain it,” he asserts. Instead, “it just moves on to something further along … something deeper. And there’s still that that mystery needing to be explained. So in other words, yokai themselves will never go away.”

So if you’re feeling anxious about the pandemic these days… go ahead and draw a picture of an Amabié, and put in your window for everyone to see. It’s not going to stop the virus, but why not have a yokai around the house? You might just feel a little bit better.

This episode is supported by the Bagri Foundation. Based in London, UK, and led by three generations of the Bagri family, the team and trustees share a spirit of curiosity. Through a diverse arts program, the Foundation celebrates extraordinary talent from across Asia and the diaspora, and encourages artistic dialogue between cultures and disciplines. Their mission is to support unique, unexpected ideas that weave traditional Asian culture with contemporary thinking.

Learn more at bagrifoundation.org.

Comments (7)

Share

Great episode! I’m one of the creators of a PC game (The Wind and Wilting Blossom) set in the Heian period of Japan that includes a lot of folklore and yokai, so this episode/article scratched a great itch.

yokai.com is a great resource if you want to learn more about specific creatures.

I’m strangely fascinated by the whole “Hello Kitty is not a cat” thing. I wonder if there is an analogy to American iconography. I’ll pose it as a question about Disney characters: “Is Goofy a dog?” Goofy talks, walks on two feet (never four), and wears clothes. He has doglike features, but he is not like Pluto, the character who walks on four feet, does not wear clothes, and does not use language. Is the Goofy vs. Pluto distinction useful in understanding what people steeped in Japanese culture mean when they say that Hello Kitty is not a cat?

I also immediately thought about the Goofy/Pluto example. But there are tons of anthropomorphic animals in film, cartoons and videogames. It just seems like in the USA we just think of Goofy and Pluto as dogs (even though they are clearly different) where in Japan they actually have a word that makes a distinction between them. Also it seems with many American anthropomorphic characters there is a backstory on why they can talk or walk on two legs. Like they where covered in toxic ooze (TMNT) or they are under a spell or a curse (the candle and tea pot from Beauty and the Beast), where in Japanese media they just exist.

This explains so much.

There’s a book by Donald Norman, one of the gods of user experience design that bumps up against this topic

https://www.nngroup.com/books/turn-signals-are-the-facial-expressions-of-auto/

I’ve lived in Japan for the last fourteen years. About the whole thing with Kitty-chan being a girl and not a cat, I feel there was one influence that was being overlooked. The Japanese love, love, LOVE making things more complicated than they need to be. Hello Kitty isn’t that complicated, but the people at Sanrio live and breath this emotionless totem day in, day out. The only way to not be driven mad by the Kafkaesque complexity is to give it the thought it’s due—none at all.

ce n’est pas un chat

Should we all get Amabie masks? Apparently they’re available… https://www.etsy.com/market/amabie