Carolyn Fisher Bastian passed away in 2011, but before she did she told her daughter-in-law, Jeanne, a story that she never forgot. Carolyn grew up in Hannibal, Missouri and remembered a family friend named Lester Gaba. Gaba had grown up in Hannibal in the early 1900s and then made a name for himself in the glamorous world of New York fashion. One day that he returned to Hannibal with his equally glamorous girlfriend, a socialite who hailed from Manhattan’s upper crust. Carolyn was invited over for an afternoon tea—it was a room full of women, dressed up, Hannibal’s high society.

Carolyn at that time was still a young girl and was given the critical task of providing snacks to the guests. This seemed like a perfect opportunity to meet this famous Cynthia everyone was talking about. She carefully took a tray of cookies around the room, table to table, person to person. When she turned to offer the tray to Cynthia, she noticed she was unresponsive. This was because Cynthia… was a mannequin. Everyone at the party was pretending like this was perfectly normal because by the time Carolyn met her, Cynthia the mannequin had already attended balls, graced the front pages of magazines, and appeared in Hollywood movies. Cynthia was a celebrity.

Lester Gaba

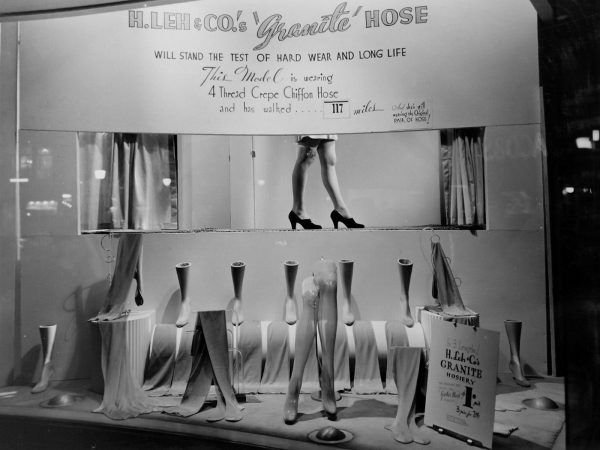

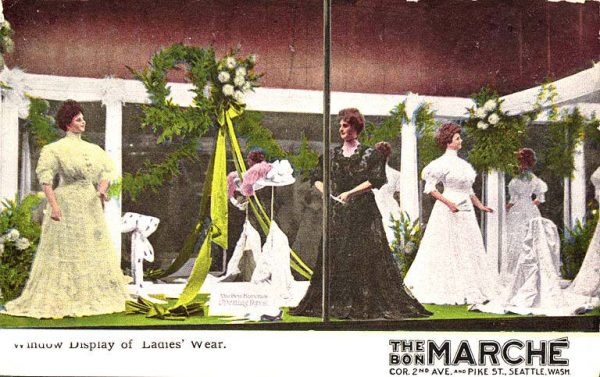

Before online ads and television, department stores had one major medium with which to display their clothes to the outside world: The window. The increased availability of plate glass in the 1800s turned storefronts into advertising spaces. And that sent mannequins, which had earlier mostly been used for fitting clothes, to the front of the store. By the early 20th century, there was a new career—window display designer.

“What the display designer wants you to do is not just look, but to stop. That’s the next stage of actually capturing your desire,” explains Sara Schneider, author of Vital Mummies. In the early 1900s, what you would be looking at was a kaleidoscopic collection of things for you to buy. Variety was what was important to consumers. “And the idea was the more you could show would entice people to come in because they would see the advantage of being able to shop in one place for everything they needed.”

The interiors of department stores were just like their window displays —they were jam-packed with attractions. Stores featured concert halls, tearooms, restaurants, and fashion shows replete with champagne. At one point, Saks Fifth Avenue installed an indoor ski slope, to help sell a line of winter wear.

Growing up in small-town Hannibal, Missouri, young Lester Gaba dreamed of entering the luxurious world of these elite department stores. His father was a shopkeeper, and as a boy, he spent most of his free time concocting elaborate displays for the shop’s front window, using whatever materials he had at hand. Lester Gaba eventually left Hannibal for good, determined to become a window display designer.

But when Gaba arrived in New York in the early 1930s, he found the department stores’ window displays lacking. Especially the mannequins. At the time, there were two main styles of mannequins. One was a holdover from the 19th century and somewhat dowdy looking. They were carved out of wax and made to be extremely lifelike, often with real human hair and eyelashes. On the hottest days, they would sometimes melt in the store window.

The other main style of mannequin at the time was a more recent invention, from the 1920s. These were art deco, abstract — human figures turned into modernist Picasso-like shapes. When Lester arrived, they would have still been considered avant-garde.

Gaba was part of a new generation of window designers who thought it was time for a change. “His aesthetic opinions were that windows needed a facelift and the windows in themselves needed personality,” says Alana Staiti, a historian at the National Museum of American History, “along with the women who inhabited those windows: the mannequins.”

Joan Crawford in a Store-Case

In 1932, Gaba wrote an article for a trade publication calling for a revolution in mannequin design. He lobbied for something that is now so common that we all just take it for granted. He wanted mannequins to embody an ideal. “Put Joan Crawford in a store-case,” wrote Gaba, “And even husbands will want to go window shopping.”

“Put Joan Crawford in a store-case and even husbands will want to go window shopping.”

At the same time, he didn’t want mannequins to be too perfect. He was aiming for a kind of believable perfection, something that the average person could see a part of themselves in. When Gaba was commissioned by Saks Fifth Avenue to create a new line of window displays, he saw it as an opportunity to make his perfect mannequin. And because he wanted it to embody this kind of plausible ideal, he decided he would model all his mannequins after real, New York society women. At the time, aspirational women weren’t models, they were socialites.

Gaba began to seek out these socialites and have them pose for him in his studio. One by one, they sat for Gaba. And, by hand, he sculpted a life-size version of each woman out of clay. He would then use the clay figure to make a mold and use the mold to make a mannequin. When he was finished, he called his new line of mannequins Gaba Girls. Gaba Girls still had more facial features than we’re used to today. They had distinct eyes, lips and skin tones. But they were no longer the hyper-realistic wax figures that had come before. Instead, they had just enough detail to give each one its own personality. But out of all the Gaba Girls, there was one whose personality stood out… at least to Lester. A mannequin he simply called Cynthia.

Cynthia

We know very little about the real person Cynthia was modeled after, except her name: Cynthia Wells. Lester likely didn’t know much about her either. “She was quite slender,” describes Staiti, “Very light-colored peach skin, blonde hair in a wig, very faint angular jawline, very small, pointed upturned nose.” But it was more than just her physical features, it was how they all added up, into a certain kind of attitude—a mix of New York high society snobbery and humility. When Gaba saw the mannequin that they had produced, he was astounded.

Cynthia’s persona was perched ever so delicately between warm intimacy and cool distance. She was the embodiment of his long sought after ideal, so Lester Gaba came up with an even more ambitious plan. It would be a marketing scheme, involving Cynthia, to help promote his new line, one that would require him to turn his own life into a kind of never-ending display. He decided to have another Cynthia mannequin made just for himself.

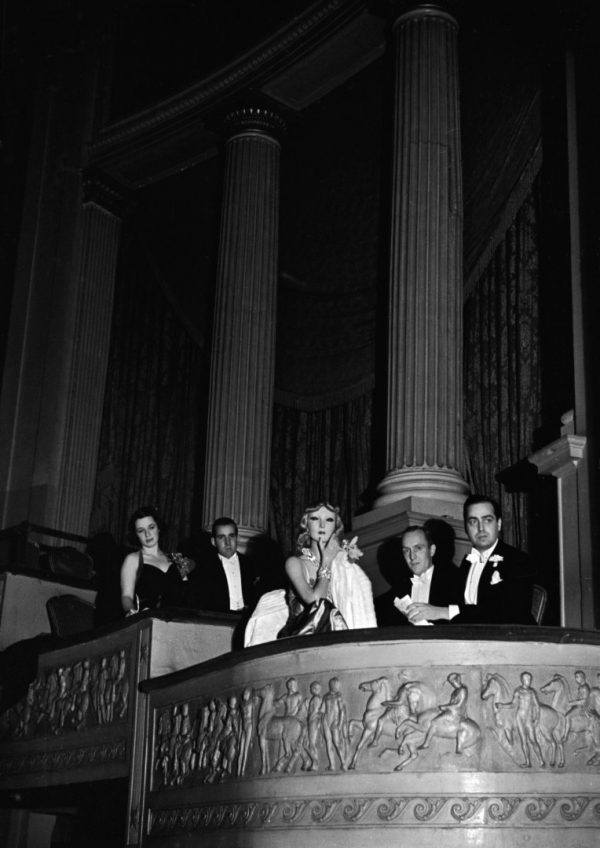

Visitors to Lester’s apartment would arrive to discover Cynthia sitting on a couch. Perhaps deeply engaged in a book, or listening to a record, like a real person. Soon he began taking her out with him as his date at events. Lester Gaba began to be seen out on the town with Cynthia, dressed up like any other young woman. The strangest part was that in every place Lester appeared with her, Cynthia was a hit. Increasingly, both friends and strangers started playing along — talking to Cynthia, telling her the latest gossip, laughing at an imaginary joke. And soon, word began to spread.

Cynthia started showing up in the society papers. City tabloids began reporting on her every move. Especially during the Depression, treating Cynthia as a real person was a way for ordinary people to participate in something glamorous. In 1937, she got a 14-page spread in Life Magazine. The profile is full of images of Cynthia — reading her fan mail, riding sitting on top of a double-decker tour bus in Manhattan, sitting next to Lester. In 1938, at her peak, she was featured in a Hollywood movie called Artists and Models Abroad.

Creating the Aura

Cynthia also reflected a fundamental change in the way clothes were beginning to be marketed. In the first few decades of the 20th century, it wasn’t just the mannequins that were changing, it was the window displays themselves. In the early window displays from the 1800s, it was still all about the products. But then store displays started becoming less about selling specific things. Department stores also wanted to sell the “aura” around the products themselves.

By the 1960s, Staiti says, this kind of marketing had fully taken over. But you can see the beginnings of it in the 30s when Lester Gaba and his contemporaries were working. They used stage lighting, elaborate props, and decorations. It was art all aimed at creating this aura of desirability around the store and its products… and mannequins played a key part. With Cynthia, Lester was able to tell a story so big that it left the store window entirely and entered the real world.

RIP Cynthia

But then, at the height of Cynthia’s fame, the US entered World War II. Lester was conscripted, and he had to leave Cynthia behind. No one is entirely sure what happened next, but the story goes that Lester shipped her back to Hannibal to stay with his mother, where he left strict instructions that she continue to be treated like a real person. One day in 1942, Cynthia was relaxing at the local beauty salon when she slipped from her beauty salon chair and shattered.

When he came home from the war, Lester Gaba apparently believed that everything could go on as before. He had another Cynthia made. But post-war America, with its turn toward middle-class consumerism and suburban living, just wasn’t interested in this new Cynthia. Cheri Magid, a playwright and professor at NYU who wrote The Gaba Girl, a play about Lester and Cynthia, says that the press ignored Cynthia … and Lester. The world had moved on. “At a certain point it just became a parlor trick or like a footnote,” explains Magid. “So he got invitations that he would have never received and then they stopped.”

Unfortunately, Lester refused to believe it was over. Even as late as the 1950s, he was still trying to get her back into the limelight with a new plan. He had her wired and rigged with an electronic speaker system to make it appear as if she was talking so that he could get her a television talk show. Gaba spent $10,000 of his own money, trying and trying to make Cynthia into a talking automaton.

The World Moved On

But the new and improved Cynthia never made any sense. All the words sounded garbled. The networks lost interest, and the television show never went anywhere. Gaba eventually turned to teaching design at a local college and writing a column about fashion display in Women’s Wear Daily, by which time most people had forgotten all about the original Gaba Girls. Over the decades, mannequins stopped looking like Cynthia. Plastic replaced plaster, mass-production replaced craftsmanship. The painstakingly crafted, unique mannequins like Cynthia went out of fashion. They were too expensive to make, too difficult to move.

No one knows whatever happened to Cynthia. In one interview, Gaba says he took her down to a friend’s attic in the East Village, where she was left to sit and gather dust. And the rest of the Gaba Girls are unaccounted for, too. One can only imagine all the Gaba Girls that must be tucked away in the basements of department stores, forgotten. And all the store clerks up above with no idea that the mannequin they’ve abandoned was once a socialite. That she once looked out over 5th Avenue, watching the crowds gaze up at her.

Comments (3)

Share

Interesting. I had no idea about Cynthia.

What a bizarre way to end the article though, with a long distance sideways film of them blowing up that American store, Macy’s. No mannequins or anything…

That’s really creepy.

I was waiting for a mention of the Ryan Gosling film Lars and the Real Girl but it never came.