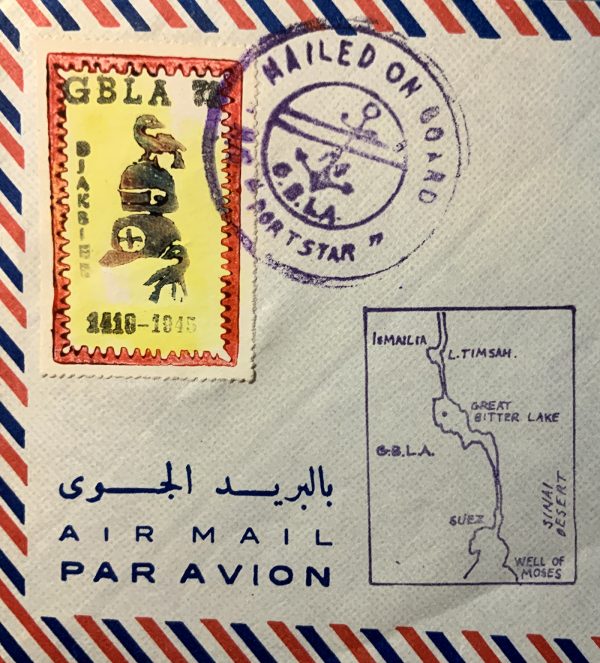

When Eric Carlson retired, he dove headfirst into an old hobby… philately. Philately is the study of postage stamps, and it’s a tragically underappreciated field of study. A stamp can give you a perfect snapshot of the past on a single square inch of paper. Carlson finds his stamps where every person with an obscure hobby does: eBay. One day he found this really odd looking stamp. “it’s a very cumbersome looking red bird in the middle […] with a yellow background,” describes Carlson.

Because stamps are usually issued by countries or postal authorities, they have clean, printed lines and tidy, professionally made images, but not this one. This stamp was kind of rough looking. The lettering was hand-drawn and the bird in the center was beautiful, but also a bit inelegant. He also didn’t recognize the letters across the top. G-B-L-A. “At first I thought it was an acronym for some nation that had escaped my attention,” recounts Carlson. But the GBLA wasn’t a nation, or a postal authority, or any type of government body. It stood for The Great Bitter Lake Association. He had stumbled upon the remnants of a forgotten bit of world history, about a stranded convoy that built a community at the center of a war.

Crisis in the Suez

When Peter Flack was 16 years old, he started a long career in the Merchant Navy working on commercial cargo ships. In the mid-1960s Flack was assigned on trade routes that took him from the UK to Asia, traveling mainly through the Suez Canal. The Suez Canal is one of the busiest and most important shipping routes in the world. It runs vertically between Egypt and the rest of the Middle East, connecting the Mediterranian to the Red Sea. Before the canal opened, fleets traveling from Asian countries to Europe had to sail an extra 4,300 miles all the way around the Cape of Good Hope.

But while Flack’s ship was busy delivering commercial goods from Singapore to the UK, tensions were escalating all around the canal. There had been border disputes and skirmishes for decades between Israel and its neighboring countries: Egypt, Jordan, and Syria. But on June 5th, 1967, things reached a breaking point. And the Six-Day War began. Unfortunately for Peter Flack, he and his ship, the Agapenor, were on their way home via the Suez Canal, which was at the heart of the conflict.

It was common for ships from different countries to pass through in a convoy together because it was easier to control traffic that way. The Agapenor was one of 14 cargo ships and two tankers grouped together. Not long into the journey, the convoy entered a section of the Suez called the Great Bitter Lake, a 100-square-mile body of salt water in the canal. Normally, a ship like the Agapenor would anchor in the Great Bitter Lake for a few hours while the flow of traffic was directed. This time, however, the ship wouldn’t be staying a few hours— it would be stuck there for years.

It was early in the morning, and Flack had just taken up his post on the bridge of the ship when he received some unsettling news from his captain. Israel had just declared war on what was then known as the United Arab Republic, and they were traveling through a potential conflict zone. It wasn’t long before Flack saw warplanes cutting through the quiet morning fast and low from the east, directly over their heads.

Around 200 Israeli fighter pilots used the low position of the rising sun, and the convoy of ships, to mask a surprise blitz on Egypt. The planes were heading westward over the Suez Canal and straight for an Egyptian airbase near the convoy’s position. Flack and the rest of the crew suddenly had front row seats to the first wave of the Six-Day War. The convoy of ships watched from their anchored positions as Israeli jets unleashed gunfire and missiles on grounded Egyptian planes.

Stranded in the Bitter Lake

Amazingly, no one in the convoy was hurt, but the Egyptian air force had been pretty much destroyed. Normally the Suez Canal runs entirely through Egyptian territory with the Sinai Peninsula on its east. After the attack, however, Israel pushed Egyptian forces completely out of the Sinai Peninsula. This turned the Suez Canal into a vertical ceasefire line that placed Egyptian forces on the west side of the Great Bitter Lake, and Israeli forces on the east. The convoy was sandwiched between two warring armies.

Cath Senker is the author of Stranded in the Six-Day War, and she says that the convoy was ordered over the radio to anchor where they were and wait for further instructions. The convoy was made up of commercial ships and had no choice but to comply with Egyptian authorities. A ceasefire was reached in less than a week, but the diplomatic conflict dragged on. Egypt ordered a complete standstill of the Suez Canal. “It was a defensive mechanism,” explains Senker, “Firstly they did not want Israel to have access to the canal […] and that way nobody could use it and no hostile power could get in there.”

Even if the 14 trapped ships wanted to leave against orders, they physically couldn’t. The Egyptian government figured the best way to prevent Israel from using the canal was to block it entirely, so a few days after the conflict started, they dumped debris, scuttled old ships, and threw in landmines to make the canal impassable. The ships were completely trapped.

The convoy of 14 ships came from 8 different nations: the UK, West Germany, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Sweden, France, Bulgaria, and the United States. In the beginning, the crews weren’t told anything because there was a complete lockdown on information reaching the ships. Despite the lack of communication, the shipping companies were working in the background to get their crews home, while the United Nations tried to work out a deal to reopen the canal. Months dragged on, and the boats still hadn’t been released. They were stranded for so long, the convoy earned the nickname the Yellow Fleet because the sandstorms in the region stained the hulls of the ships.

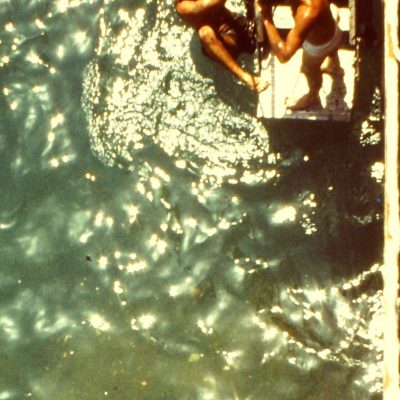

Flack handled the idle time well. He remembers they would play darts, swim, sing songs, and play cards to pass the time. A lot of men had a tough time handling the situation though. “There were others who didn’t accept it—biting at the bit. But I thought well this is our lot.” After three months a compromise was finally reached. There was no way Egypt would reopen the Suez Canal, but the people trapped on-board were released. Peter Flack and the rest of the stranded crew finally went home.

The New Recruits

But the shipping companies didn’t want to completely abandon their vessels in the Suez Canal. It was possible the canal would open back up soon. Not to mention these were expensive ships, packed with valuable cargo. “The logical thing to do was to keep people there to protect the valuable cargo and the investment that they’d made in the ships,” says Senker. Every shipping company decided to recruit new crew members to keep the ships in working condition with the understanding they would set sail the moment the passage was finally cleared.

George Wharton was one of the members of that first relief crew. Wharton says the work was like being on any other ship. There was a lot of cleaning, running the engines, and checking the cargo to make sure it kept fresh in the hot climate. But since they were in the middle of a lake, in the middle of a desert, in the middle of a war zone, Wharton says it was hard to get supplies. “We started to run out of stores. You weren’t going hungry or anything but here you were limited to the variety if you like,” says Wharton. But the crews realized that among the fourteen ships, they actually had plenty.

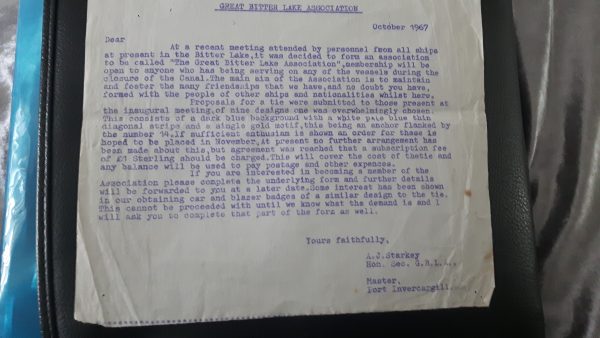

Soon, they started hanging out a lot, and because they were a bunch of young sailors, they started partying a lot. Some of the captains became worried that with the amount of idle time on the ships, people would start to get bored and acting badly. “There was of a lot of drinking, and […] hanging out, and sleeping and they were thinking it would be good to get together and organize some social activities,” explains Senker. The captains figured a little structure would curb the worst behavior of their sailors, so in October of 1967, five months after the start of the Six-Day War, they founded the Great Bitter Lake Association.

The Great Bitter Lake Association was a way to regulate the unofficial marketplace that had sprung up between the ships, and bring some order to their makeshift community. It was also a social committee. Membership in the GBLA included events hosted each week by a different vessel. Ships modified their lifeboats into sailboats and took turns hosting regattas. One ship built a functional soccer pitch on its deck and held tournaments. The Polish ship had a doctor and became the de facto medical center. The Swedish ship had a gym.

But even though the Great Bitter Lake Association was originally formed to curb drinking, a lot of alcohol was still consumed in the Great Bitter Lake. One ship captain estimated that perhaps 1.5 million empty beer bottles may have been dumped into the lake, writing, “One wonders what future archaeologists in a few thousand years’ time will think of this.”

The association was about providing a sense of stability in an incredibly unstable place. They weren’t just individuals on a ship, but members of a society. They were actually given a specially designed tie and a badge. The badge itself was in the shape of a shield, with a large anchor across the center. At the top were the letters GBLA and at the bottom was the number 14 for the 14 ships in the lake. Running diagonally behind the anchor was a thin blue strip to represent the Suez Canal.

Towards the end of Wharton’s stint on the lake, the crews came together to celebrate their first big holiday as a group. Wharton fondly remembers, “The Polish seamen made this huge Christmas tree and mounted it on a raft and anchored it in the middle of all the ships. And on Christmas night all the boats were invited over to the tree. And we all tied off around the tree, and we had a carol service. One of the boats actually had an organ in it, you know a piano organ. And so we had music and some carols.”

Cinderellas of the Lake

Wharton happily returned home after the holidays to his wife and brand new daughter. He figured his time on the lake was a once in a lifetime experience, but to his surprise, a year later, the UN still hadn’t figured out a solution. The ships were still in the canal. And he was given a chance to go back. When he got back to the lake Wharton realized that not only was the association was still going, it was getting more creative. Between the brotherhood, the sports, and the official badges, the Great Bitter Lake Association started feeling like something bigger than just a club, but more like its own nation. “Therefore as a little nation they should have their own postage stamps,” says Senker.

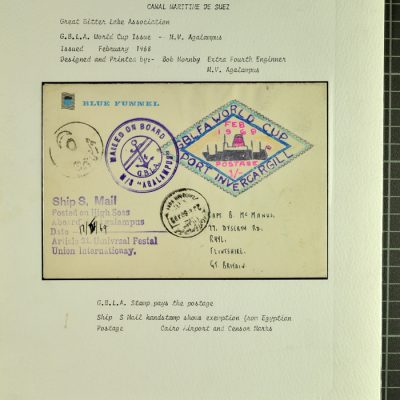

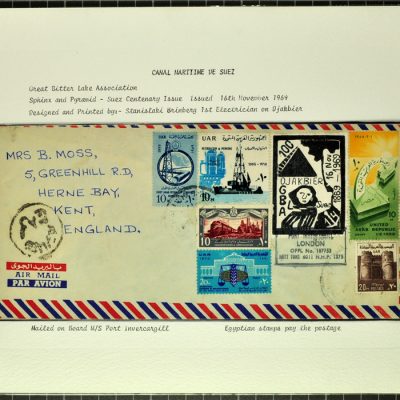

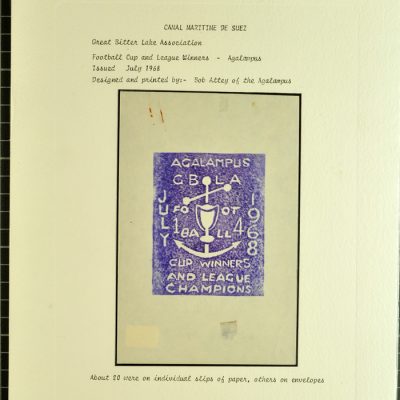

Technically these stamps were Cinderella stamps, which means they had no postal value and were made mostly for their own amusement, but some actually made it through as official postage. Each stamp was hand-drawn or painted using whatever materials they could find— for example, crayons, coffee, potato skins—and then copies were printed and distributed to all of the members of the GBLA to use.

The stamps featured common motifs like birds to represent the seafarers’ longing for freedom. There were ships and anchors. The artwork on each stamp acted like a tiny time capsule of their experiences. They documented Christmases, anniversaries, soccer tournaments, even a Great Bitter Lake Olympics they held in honor of the 1968 Mexico City games.

A deal was finally brokered in 1974 to reopen the Suez Canal, but by this point, the heyday of the GBLA was over. The American vessel, the African Glen, was hit by a stray missile during the 1973 Yom Kippur War and sank but thankfully, no one was killed. Throughout this whole time, the shipping companies kept sending skeleton crews out to look after the ships, which were slowly decaying. By 1974, most of them were no longer seaworthy.

It took a full year to remove the 100 bridge sections, 20 trucks, 8 tanks, 100 vessels and 750,000 explosive devices thrown into the waters of the Suez. But in 1975, eight years after the start of the Six-Day War, the ships said their final goodbyes to the Great Bitter Lake. They even commemorated the moment with one last set of farewell stamps.

Most of the ships in the Great Bitter Lake needed to be towed out of the canal. Only the two West German vessels were capable of leaving under their own steam, and for the Germans, their patience paid off. They had been carrying raw materials like wool, steel, lead, and ore sand for making sandpaper, and these goods had actually increased in value. “It proved to be a thousand percent more profitable than it had originally been,” says Senker. Both ships had an epic welcome back in Hamburg. Around 30,000 cheering spectators came out to see them dock at their home port. “They did actually make a world record,” says Senker, “The two German ships were the Münsterland and the Nordwind, and it was the Munsterland that made the world record as the longest sea shipping voyage in history which was eight years, three months, and five days.

From 1967 to 1975, over 3,000 men (and one woman actually) served on the Great Bitter Lake. In 2017 a fifty-year reunion was held in Liverpool, and members in Germany and Slovakia still meet up annually. It remains a quiet tradition fifty plus years later. The GBLA is mostly a footnote in the complicated history of the Six-Day War. But there are little pieces here and there that remind the rest of the world that this makeshift nation once existed. You can find them in a well-designed badge, a custom necktie, or in a stamp that you stumble across on eBay.

From the Panama Canal coda: below is the flag of Panama proposed by Philippe Bunau-Varilla and the current flag which was designed by the first family of Panama.

Comments (12)

Share

SUCH a cool episode! The camaraderie between these 14 ships was such fun to imagine whilst listening on my way to work. I had never heard of this story, and enjoyed every minute.

no flag?

Photos of the flags are now posted on the website. Enjoy!

Thank you very much for producing this podcast – it’s great to see and hear it!

I’ve written a post about the GBLA podcast here: https://cathsenker.co.uk/the-cinderella-stamps/

Another wonderful podcast from 99% Invisible. But, I would like to question Roman’s support for the Panamanian flag. Ok, from a purely design point of view it is lovely, but how does it really reflect the country? The Panama flag seems more to be just another red/white/blue with two stars that reflects the US government’s desire to take control of an important piece of geography. I would say Maria de la Ossa and friends were more interested in pleasing the US than concern about the future prosperity and independence of their new little country. Panama’s successful control of the canal for the last 20 years is finally allowing the country to develop. Their future is bright and I hope someone will design them a new flag.

Thank you Vivian for a great episode! This story would make a great movie, don’t you think?

Another great episode!! I agree this would make a great movie.

Just happened to get to this as i backfill old eps. So topical!

(given EVER GIVEN a grounded giant container ship blocking the Suez right now: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/mar/25/suez-canal-blocked-ship-ever-given-stuck )

Also great story. What a unique old school T.A.Z.

Thanks!

thinking about this episode again for obvious reasons but also because I just listened to a talk from Hester Blum at Penn State whose book News at the End of the World includes a study of printing aboard polar exploration ships (newspapers created on board for example) and it got me thinking about *how* the stamps were copied. We’re there presses on board to create the copies?

I had a little TICKLE in the back of my brain every time I saw the suez canal in the news recently and then finally this came back to mind. Loved loved LOVED this episode last time I listened and the relisten was even better.

thinking about this episode again for obvious reasons but also because I just listened to a talk from Hester Blum at Penn State whose book News at the End of the World includes a study of printing aboard polar exploration ships