The largest city in North America, Mexico City, sits at the center of a high valley, 7,000 feet in the air, surrounded by volcanoes. Over a millennium and a half ago, a volcano called Xitle erupted. Molten lava poured into the valley and covered around 30 square miles in a bed of volcanic rock. Today, most of this lava field has been paved over with roads and buildings and parking lots, but there is still one area where the volcanic rock can be observed on the surface.

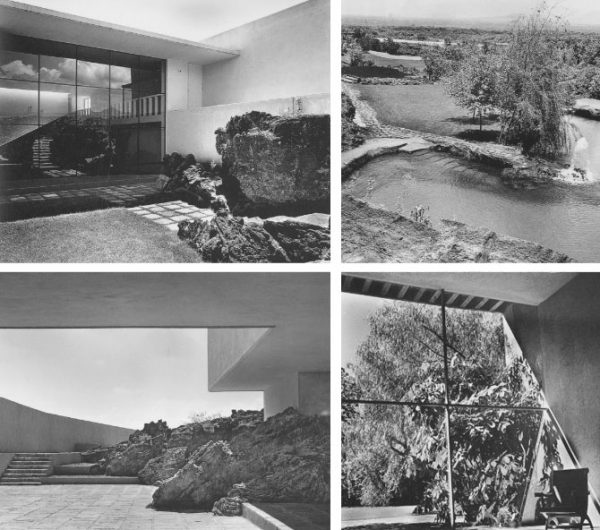

Geological features and natural landscape of El Pedregal, images by Emmett FitzGerald

The Pedregal de San Angel Ecological Reserve is a small park in South Mexico City where visitors can observe swirls and folds in rocky outcroppings, remnants of the lava that flowed and cooled centuries ago. When the area is hot and dry, brown grasses creep up through the cracks, but when the seasonal rains come, the landscape transforms, bursting with color as various plants begin to bloom.

Back in the 1940s, this unusual landscape became a source of inspiration for Mexican Modernist architect Luis Barragán. Famous for his bold uses of color and careful integration of natural light, he designed a number of homes among the rocks of El Pedregal. In attempting to build harmoniously with this volcanic landscape, however, Barragán may have accidentally contributed to an ecological crisis that’s playing out in Mexico City today.

Paving Paradise

Luis Barragán moved to Mexico City from Guadalajara in the late 1930s. The city was in the middle of a building boom, but around 10 miles south of the city center, El Pedregal remained relatively undeveloped. Barragán and his artist friends would go on weekend hikes in the lava field. In part, they were enamored with this landscape that felt distinctly Mexican. “It was a place that the Spanish had never tamed … had never colonized,” explains Keith Eggener, an architectural historian at the University of Oregon. “It was a place with views of the volcanoes that were central to a lot of Mexican mythology and Mexican history.”

For years the uneven rocky landscape deterred would-be developers, but Barragán saw the lava as an asset. He decided to populate the place with modern houses while leaving much of the lava and natural vegetation in place. Like Frank Lloyd Wright did with Fallingwater, Barragan would integrate the landscape into his designs. The homes themselves would be simple and modern, made of local materials and deferring to their context. In some places, the lava rock would even intrude into the buildings. The streets would follow the contours of the rocks as well. Much of the land would be left open and unbuilt.

Barragán hired a photographer named Armando Salas Portugal to capture the spirit of this place. Salas Portugal’s photos of well-to-do Mexican families wandering through the rock gardens helped sell Barragán’s lava lifestyle to the Mexico City elite. By the early 1950s, though, his vision of harmony between building and landscape began to lose out to rapid urban development. El Pedregal was a source of cheap land not far from the expanding city. Barragán got bought out of the project, and the volcanic rocks that drew him to this place were covered up with driveways and lawns and swimming pools. By the 1980s, nearly the entire lava field had been developed. The loss of the landscape is a problem, and not just an aesthetic one. Covering up the unique geology of the area has contributed to bigger problems for a region struggling to manage an essential natural resource: water.

Feast or Famine

For centuries, the Valley of Mexico was filled with a series of rainwater lakes. The Aztecs built their capital Tenochtitlan on an island in the middle of one of those lakes. They constructed causeways and canals and floating gardens. It was like the Venice of Mesoamerica.

When Spanish conquistadors sacked Tenochtitlan, they rebuilt a modern city with a grid. This new metropolis, however, would flood regularly, eventually leading to efforts to drain the former lakes of the basin. Over the course of the next several centuries, Mexico City built an elaborate system of tunnels designed to evacuate rainwater out of the basin and preventing flooding. Little by little, the city drained the lakes and expanded out over the dry lakebed.

Mexico City still has major flooding issues to this day, but it also faces a seemingly paradoxical problem: it’s running out of water. All of the infrastructure aimed at draining the rainwater from the basin works against efforts to retain water for human consumption. Today, many neighborhoods in Mexico City don’t have reliable running water — and when the rainy season comes, those same neighborhoods get far too much water all at once.

To solve the scarcity issue, the city began piping water in from far away but also pumping it up from the aquifer below, creating yet another problem: the city is sinking. As the water was sucked up, the ground began to crack and crumble like a stale cookie, resulting in different rates of subsidence. Meanwhile, rainwater which should be replenishing the ground can’t penetrate it thanks to impermeable paved surfaces above.

Landscape Archeology

So Mexico City is flooded, thirsty, and sinking — it’s a complicated problem with no simple solution, but local landscape architect Pedro Camarena thinks that one obvious place to start is El Pedregal. The buried lava rock in that area is filled with lots of little holes — making it extremely permeable. In most places throughout the city, aquifer recharge is extremely challenging, but Camarena says that uncovering the porous lava rock in El Pedregal would allow rainwater to flow back to the aquifer underground.

Removing all kinds of modern surface development is unfeasible, but Pedro Camarena thinks that there are lots of opportunities to strip away the pavement, expose the lava and make the urban landscape more permeable. Unnecessary parking lots and medians and other bits of infrastructure could be removed in an effort to restore the old lava field and increase aquifer recharge. Homeowners, too, could help if they can be convinced to dig up their modern lawns and embrace rustic lava rock gardens, realizing something akin to Barragán’s initial vision. Already, some residents are taking up the cause alongside locals like Camarena.

When Camarena was asked to design a garden to go with a public art sculpture on the Pedregal, he didn’t begin planting flowers as one might expect. Instead, he started digging, exposing the lava landscape below ground. He calls this approach “landscape archeology” — uncovering rather than covering, subtractive rather than additive. Much like Barragán did over half a century ago, Camarena hopes to inspire an appreciation of the historic landscape of the region.

Rock gardens alone aren’t going to solve the water crisis, but they do help — and they raise awareness of the city’s history and unbalanced relationship with its groundwater.

A huge thanks this week to reporter Zoë Schlanger. We learned about Pedro Camarena and his work from her fantastic piece in Quartz. Check out more of Zoë’s environmental reporting on her website, including this series about water issues along the US Mexico border.

Comments (2)

Share

Check out the public water square in Rotterdam. It might be 1 of the solutions for Mexico City.

https://www.watersensitiverotterdam.nl/plekken/waterplein-benthemplein/

Thanks for this episode about my city. I just wanted to comment that the lava is not gone at all. I can see it everywhere at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, where I work. My mother in law’s neighborhood is built on top of it, with big chunks of rippled black rock showing. People come to UNAM to practice climbing on 30-foot lava walls. The lava is not going anywhere.