Few creative professions can point to a single figure as famous in their field as Frank Lloyd Wright. This architect’s legacy includes some of the most iconic and gorgeous buildings in the United States, such as the spiraling Guggenheim Museum in New York, the Fallingwater house in Pennsylvania, and the futuristic Marin County Civic Center in California.

By the end of his career, Wright had achieved a level of celebrity usually reserved for actors and rock stars. His was a household name, and he was recognizable by his distinctive hat, cape, and cane. He weighed in publicly on society, politics and religion, and he unabashedly claimed to be the greatest architect in the world. “You see,” he said in an interview, “early in life I had to choose between honest arrogance and hypocritical humility. I chose honest arrogance and see no occasion to change now.”

Frank Lloyd Wright went through a number of scandals in his lifetime. He was the subject of lawsuits and property seizures, and constantly in debt or getting divorced. He was often criticized for his lack of professional conduct and general rudeness. He was largely characterized as arrogant and self-obsessed.

Fallingwater (left) and Guggenheim Museum (right) by Jean-Christophe Benoist (CC BY 3.0)

But this bombastic character ultimately changed the field of architecture, and not just through his big, famous buildings. Before designing many of his most well-known works, Wright created a small and inexpensive yet beautiful house. This modest home would go on to shape the way working- and middle-class Americans live to this day.

At Home in Usonia 1

Herbert and Katherine Jacobs lived in Milwaukee for two more years before a slightly higher-paying journalism job drew them to Madison. When they arrived, they found most houses to be unaffordable on the salary of a newspaperman. At the suggestion of his wife’s cousin, the Jacobses set a meeting with Wright to see if perhaps the great architect would be interested in building them a modest home.

In the past, when Frank Lloyd Wright had designed private homes, it had generally been for a wealthier clientele (like the nearly 10,000-square-foot Robie House shown below).

Unsure of how to hook such an architect for their modest home, the Jacobses put it to him as a challenge: could he build them a nice house for $5,000 (around $85,000 in today’s dollars)? According to Jacobs, Wright responded that he had waited for decades for someone to ask him just that question.

Wright had long wanted to make a more democratic form of housing. He had experimented with inexpensive building methods and visionary urban (and suburban) design ideas. Now he had a chance to put some of these experiments and ideas into practice in a single project.

The Jacobs family would own the first house in a movement Wright called Usonia. This was a word he used to refer to an idealized vision of the United States at its democratic zenith. Usonia, Wright imagined, would be a nation of modest but comfortable, well-made and beautiful homes for the working- and middle-classes.

Usonia embodied an idea that proper architecture could shape culture — design could make the world a better place. A beautiful house, Wright thought, would inspire its residents to eat better, dress better, listen to better music, and be better people.

For Wright, housing the American people was a matter of individualization, mass-customization, rather than cookie-cutter mass-production . He saw America as a country of individuals, and his vision for the nation was one of decentralization, where people would spread out away from cities on private lots (a Utopian vision of suburbia), living independently, humbly, within nature.

“The city, of course, is a thing of the past,” claimed Wright. “There was a time during the middle ages when it was the only source of culture. There was no way of acquiring this thing we call culture except by direct contact, see.” But now that people had cars, radios and telephones, there was no need to congregate in dense urban clusters.

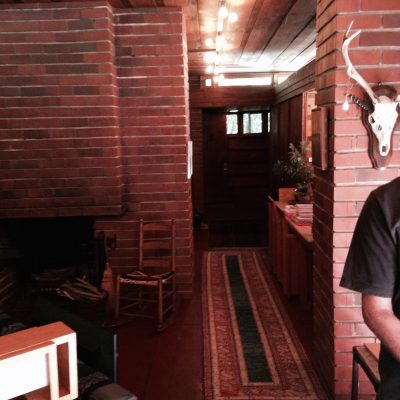

The first of its kind, the Jacobs House would become known as Jacobs 1, or Usonia 1. It is located in the suburbs of Madison and stands out very obviously from the surrounding homes. From the street and at a glance, it looks like a wooden wall — the house turns its back on the road. On the other side, expansive glass opens the home up to nature. It was designed for its occupants, not to show off to neighbors.

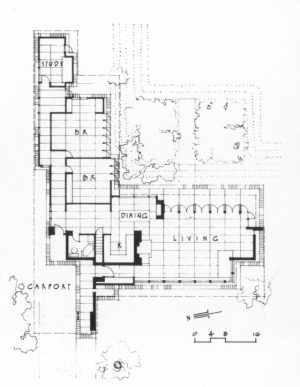

Usonia 1 also features a carport, a now-familiar term reportedly coined by Wright. Instead of a garage, a wooden awning offers shelter for cars. This was a cost-saving measure as well as a lifestyle-shaping device, forcing occupants to discard rather than store extra stuff. And like so many of Wright’s architectural works, it is more than it first appears — a closer look reveals careful detailing in the arrangement of wood slats.

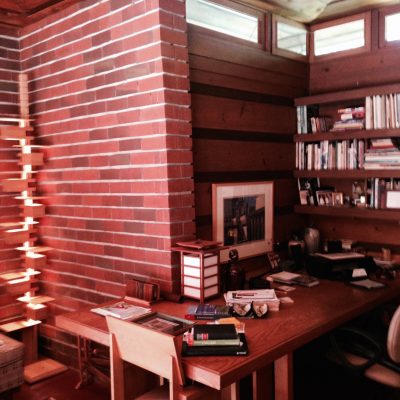

Usonia 1 carport and interiors by Avery Trufelman

Inside, the space is small but floor plan is open. There are no walls between the kitchen, living and dining rooms. Again, this was both a design strategy and cost-saving measure, of which there are many examples within the home. The lights on the ceiling, for instance, are just bare sockets with wires running through a steel channel — this is widely considered the first example of track lighting. Flat roofs, built-in furniture, and heated floors were also unusual if not unique features.

Not all of Wright’s strategies to save money on the construction of Usonia 1 were entirely above-board. He had his apprentices steal some bricks from another building of his that was under construction nearby, for instance, to save money on materials. These bricks from the Johnson Wax Building were curved, adding waves to flat walls. Wright also kept costs down by reducing his own fee to just $450, which was generous but also not a sustainable cost-saving solution going forward.

Still, though it had issues (like rain drainage) and was missing some things (like window screens), Wright managed to meet his target of building a low-cost home for the family.

The resulting house was small, but it worked for the family for a time. They moved out six years later having had two more children, but were clearly pleased with their residence since they once again commissioned Wright to build their next house.

A Vision of Usonia the Beautiful

In Wright’s perfect world, he would custom-design houses for everyone. And not just the architecture — he would design the dishes, furniture, maybe even the clothes (he once designed a dress for the wife of a client). This was all about changing culture, one home at a time, and by extension redesigning America. Good design, he believed, would make the country more beautiful but also enlightened.

By the end of the 1930s, Wright had designed Usonian homes around the country, in states including Alabama, California, Illinois, Michigan and Virginia. But this was just the beginning of his vision. He wanted to create a central factory that made prefabricated Usonian parts, modifiable for each client, depending on their needs for space and site conditions — a factory for mass-customization.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s factory for Usonian homes never came to be. And it became increasingly clear to Wright that the $5,000 dollar price tag for Usonian homes wasn’t feasible in the post-Depression era as materials and labor became increasingly expensive. Meanwhile, Wright’s career picked up shortly after Usonia 1. He started getting bigger commissions again.

While Wright continued to work on Usonian homes within his lifetime, he would never find time to fully realize his vision. In the end, it was a group of his apprentices that would carry on his ideals by building an entire community of Usonian houses right outside of New York City.

Usonian houses in New York as seen from the streets by Avery Trufelman

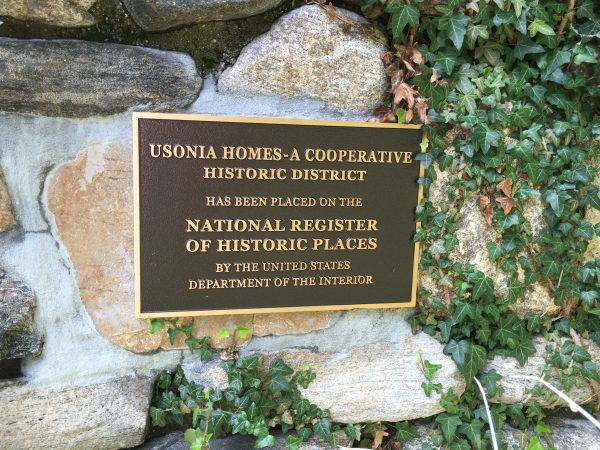

Nestled in leafy hills near Pleasantville (about an hour north of Manhattan) sits Usonia, NY. Its unique homes feature low, flat roofs and are tucked into the trees so you can hardly see them on lush summer days. There is no big welcome sign or gift shop, but in the middle of the community there is a plaque:

This community was started in 1944 by a few of Wright’s disciples who had studied at his school, Taliesin — most notably a man named David Henken. He sought out similarly-minded people who would invest in and join this new community.

Would-be residents were drawn to the project by a combination of factors, including the promise of affordable housing, shared democratic ideals and (of course) the involvement of Frank Lloyd Wright, a famous architect.

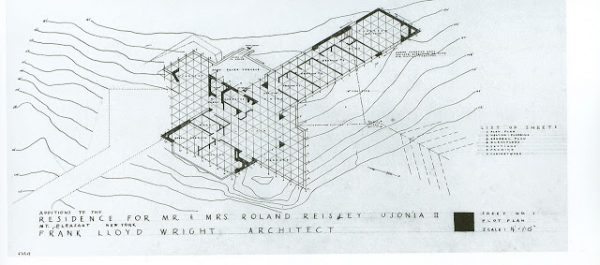

Participants in this experimental endeavor were optimistic and stuck with the project despite cost overages. Wright himself ended up designing three of the houses in Usonia.

People tended to stick around this strange little town. Indeed, during the first 40 years of Usonia’s existence, only 12 of the 48 houses changed hands (and half of those went to next-generation residents). Reisley jokes that there were few divorces because couples couldn’t decide who would get to keep their Usonian home.

Over time, though, life started to move at different paces for people living in Usonia. Younger families grew older and generations shifted.

And when people did decide to sell their homes, prospective buyers were thrown off by the cooperative nature of the village — in the first decades of Usonia, members didn’t even own their homes. A compromise was eventually reached: the land would remain communal but the houses would become individually owned (thus easier to sell).

For newcomers, whose homes were not built specifically to their needs, life in a Usonian home could require a bit of adjustment. Most of the houses in the community have been expanded or remodeled. However, the board of Usonia ensures that all new additions match the original architecture, and are made with local materials, flat roofs, big glass windows and other signature Wrightian features.

Many Usonian homes are also hard to modify for various reasons. Owners, of course, want to preserve aspects of their house’s history. But in many cases (within and beyond Usonia, New York) there are also boards and preservationists who can make it difficult to engage in big remodeling projects. At the same time, there is an argument for adapting these buildings as they age: preserving a house means keeping it occupied and updated, which in turn means upgrading things to make it livable across generations.

No one is quite sure how many Usonian homes even exist today across the country. Estimates range from a few dozen to well over a hundred. It depends, in part, on how one defines a “Usonian” home. Does it refer to designs done specifically by Wright and his apprentices? Is it a period of architectural history? Or is it simply an architectural style? On some definitions, Usonian homes are still being constructed today. There is, for instance, a Usonian structure recently built by Florida Southern College that was designed by Wright in 1939 but built 74 years later.

Beyond the community in New York (if even there), Usonia never came to exist in the way Frank Lloyd Wright originally envisioned, with Americans living in an affordable yet custom home. Still, Usonian designs and ideals came to influence other architectural trends, including long and low-to-the-ground suburban ranch-style homes popular from the 1940s onward.

Like Wright’s Usonian homes, ranch houses often have open floor plans with few walls and low-angled roofs. Other small aspects of ranch homes, like sliding glass doors that create connections between interior and exterior spaces, also recall aspects of Usonian approaches. At the same time, many ranch homes use off-the-shelf parts and feature painted surfaces rather than natural materials, very clearly different from Wright’s organic aesthetic.

Wright might not have been pleased that the concepts of Usonia got absorbed into cookie-cutter suburban homes. But these descendants of Usonia did what Wright’s designs could not: they made houses affordable for the middle-class American family. One might say that Wright’s dream was realized, just not quite as he dreamed it.

Frank Lloyd Wright died in 1959 at age 92, three years after finishing the Reisley House in New York. But his influence persists — you can see it in everyday things like suburban ranch homes, carports and track lighting. It is also visible in creative uses of natural brick, stone, wood and concrete, in big open floor plans and in buildings that respond to their environments. In little elements and details all around us, Usonia lives on, in ways Wright never would have imagined.

Comments (11)

Share

Roman Mars is the Frank Lloyd Wright of podcasting!

Taliesin may mean ‘shining brow’ but it has a further significance.

‘Taliesin’ was the name of the legendary Welsh bard, sometimes called Taliesin Ben Beirdd (Taliesin Chief of Bards).

Wright was placing his home in a lineage of great artists.

It would be interesting to include aspects of Taliesen West, located in Scottsdale, AZ, in your redux – that was where I first really learned to appreciate some of FLW’s style in how he kept the desert out – or, better said, let the desert in the cleverly designed spaces. It would be an interesting complement to the architecture designed for a cooler, NY/PA climate.

What would Frank Lloyd Wright think of the Earth Ships in Taos New Mexico?

https://www.earthshipglobal.com/ https://www.earthshipglobal.com/the-phoenix-earthship

Loved this story but as an old radio guy I can help but wish you would identify the iconic voices, like Mike Wallace and Howard K. Smith which pop up in your pieces so often. That’s all. Thanks.

Roman, Avery, and team,

I am a longtime listener, starting before episode 25, but a first just occurred! Our worlds overlapped directly for the first time. It was a pleasure to hear Prof John Moore and his wife Betty who currently live in the Jacobs 2 home. I met them when I was a graduate student at University of Wisconsin.

As a chemist working at a large corporation known for innovation in MN (hint hint), I constantly hear interesting design stories, and I love the varied and thought provoking stories you bring my way. Keep them coming and I hope to overlap again. Feel free to reach out if insight from a chemist working in Electric Vehicles is ever needed.

Roman and team,

I have been listening for nearly 7 years, and I can say 99PI has been in my ears for longer than any other podcast I’ve come across. However this evening was a first for me, as our world’s overlapped when I heard Prof John Moore and his wife Betty discussing their home in Madison WI in the Usonia episode.

I hope the overlap occurs again soon. As a technology and product developer at a MN based corporation known for innovation, I live in the world of design. Your interesting and thought provoking material often provides the muse to consider professional…or personal….problems differently. Reach out if a chat with a chemist working in Electric Vehicles would be of use. In the meantime, keep up the good work.

My office is about 15 minutes from Usonia Road, and I never knew. I’ll definitely have to drive through one of these evenings.

Another great episode about architecture. Hearing this show makes me wanna become an architect….

This episode feels like it was written all around me. During my teen years, the early 60s I lived in a Eichler in Palo Alto. Eichlers perhaps defined mid century modern. They were definitely patternes after Usonian houses. The house was relatively inexpensive but had a back wall that was entirely windows. It was open concept before the term was invented. The heat was in the floors and the floor surface was sheet cork. Wonderful. Even better they had brought the heating element closer to the surface right in front of the toilets so there was a warm spot there. Ours was a cheap Eichler model the later more expensive ones were even nicer. That house defined the basics of ‘nice house’ for me.

Now 55 years later we are massively remodeling our house in Tucson and No surprise, the back of the house is a 15′ wall of windows looking out at a 7000′ mountain range.

A wonderful podcast. It made me miss Wright’s Pope-Leighey House (and original owner Loren Pope) in Alexandria, VA where I was a docent for many years back in the 20th century! http://www.woodlawnpopeleighey.org/aboutpope-leighey