When 99% Invisible producer Katie Mingle’s father Jim Mingle retired, he began walking —a lot. He’d always been a walker, but with more time, he took up long-distance, multi-day trips. And even though he’s an American, he mostly preferred to walk in the UK. In fact, over the course of a decade, he walked the entire length of Great Britain.

On one of his many trips, Jim found he needed to hitchhike (rather than walk) back to the village where he was staying. A jeep pulled up and he hopped in. The driver was dressed in a traditional tweed outfit with a funny cap. He introduced himself as the gamekeeper for Madonna and her then husband, Guy Ritchie. Katie’s dad had been walking across their private estate.

This walk across private land was not unusual. Thousands of distance walkers in Britain, regularly do the same thing , which is different from what people typically do in the United States. If you wanted to walk across America, you’d have to do it on a combination of public trails and roads and you certainly couldn’t cut across Madonna’s property.

In the United Kingdom, the freedom to walk through private land is known as “the right to roam.” The movement to win this right was started in the 1930s by a rebellious group of young people who called themselves “ramblers” and spent their days working in the factories of Manchester, England.

Manchester was a dirty, grimy industrial town in the 1930s, but close to a beautiful area known as the Peak District. However, this open countryside was closed to the workers of Manchester at the time.

It hadn’t always been this way. For hundreds of years, an idea of “the commons” had existed in England. From about the 5th to the 15th century, kings and lords controlled all the land but peasants had rights to live on it and use it in exchange for various type of service.

Ken Ilgunas, author of This Land is Our Land, says that peasants in England could graze their cattle, cut lumber, draw water and collect peat from these common lands.

Beginning in the 1400s, when wool prices rose across Europe, landowners began fencing their land in order to graze sheep more efficiently —an act that became known as “enclosure.” Landowners cleared entire villages of people, making them homeless, and put up stone walls and hedges to mark the boundaries of their property.

Over the years, Parliament created more and more laws to keep landless farmers and agricultural workers from using what was once common land. From 1760 to 1870, about a sixth of England went from common lands to enclosed private property.

People were so desperate to continue hunting on this once-common land that they came at night and covered their faces in soot for extra camouflage. They were known as “the blacks,” and in 1723 Parliament passed the Black Act, which created a number of offences related to trespass, some of which were punishable by death.

Eventually the death penalty for trespassing was eliminated, but the land remained closed to the vast majority of people. As England industrialized in the 1800s, workers were further separated from the land and unable to find places for recreation.

England did not have a national park system at this time, and the trails that people could access were extremely limited. They walked where they could and trespassed where they couldn’t. They climbed over fences and tried to stay hidden from the gamekeepers. And all over England, so-called rambling clubs started to form. And in polluted, industrial 1930s Manchester, there was a rambling club called the British Worker’s Sports Federation and a charismatic member named Benny Rothman.

One day, a few people from Benny’s group were walking in the hills near Manchester, but they were soon chased off by gamekeepers employed by the landowner. Benny and the other ramblers thought: if there were enough of us they couldn’t stop us. Let’s get a huge group together and walk onto this mountain called Kinder Scout.

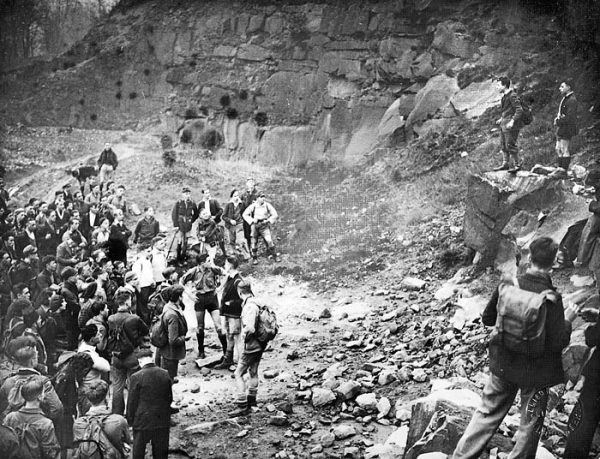

A motley crew of hikers gathered at the base of the mountain, and Benny Rothman talked about the rights they had lost during the enclosure acts. He emphasized that the trespass on Kinder Scout was meant to be peaceful. And with that, the group set off up the mountain. At some point, the hikers did have a small scuffle with some gamekeepers, but the keepers backed off after they realized they were outnumbered.

The trespass was a success. They openly walked on Kinder Scout and it all probably would have ended right there if the police hadn’t decided to make some arrests. Six ringleaders were arrested and five were later given prison sentences from two to six months. The effect of this was to give the trespass national attention and a lot of popular support.

The young ramblers of Manchester had set in motion changes that would transform how England thinks about private property. The Kinder Scout trespass has been described as one of the most successful acts of civil disobedience ever in the history of the country.

A folk singer named Ewan MacColl memorialized the event with a song:

… I’m a rambler from Manchester way

I get all me pleasure the hard moorland way

I may be a wage slave on Monday

but I am a free man on Sunday.

After the trespass, the rambling groups continued to push for expanded access. There were more trespasses, and in 1951, when Britain opened its first national park, it was in the Peak District.

But it wasn’t until the year 2000 that the ramblers got what they always wanted — an act of Parliament that opened up huge sections of the country where people could roam free.

Other European countries have similar laws, and some have gone even further. Norway, Finland, Sweden and Scotland provide nearly universal access to the whole countryside.

In the United States, we have an incredible system of national parks, but very few rights to wander through private property. The idea of opening up private land to the public seems almost un-American.

But that wasn’t always the case. In the early days of this country, it was common practice to hunt and fish on private land if it wasn’t enclosed by a fence. In an 1862 essay entitled, “Walking,” Henry David Thoreau wrote that he feared that one day, “walking over the surface of God’s earth shall be construed to mean trespassing on some gentleman’s grounds.” That day may have come even sooner than Thoreau feared. Ken Ilgunas says our concept of private property began to change just a few years later, following the Civil War. Louisiana, shortly after the end of the war, criminalized trespassing in part as a response to former slaves now having free access to the countryside.

But that wasn’t always the case. In the early days of this country, it was common practice to hunt and fish on private land if it wasn’t enclosed by a fence. In an 1862 essay entitled, “Walking,” Henry David Thoreau wrote that he feared that one day, “walking over the surface of God’s earth shall be construed to mean trespassing on some gentleman’s grounds.” That day may have come even sooner than Thoreau feared. Ken Ilgunas says our concept of private property began to change just a few years later, following the Civil War. Louisiana, shortly after the end of the war, criminalized trespassing in part as a response to former slaves now having free access to the countryside.

There were other reasons as well. With the invention of barbed wire, the open ranges all but disappeared. Native Americans were forced off their communal lands onto reservations. The land was then sold to settlers and fenced. Land-grants to the railroads and the Homestead Act of 1862 turned great swaths of public land to private ownership.

Ken Ilgunas believes Americans should be fighting for the kind of recreational access that exists in many European countries. And so does Jim Mingle, who loved the freedom to walk across private land. “It felt like the whole country was open to you,” he says.

Comments (24)

Share

I loved this episode. I’m also surprised you didn’t mention the quintessential American rambling song “This Land Is Your Land” by Woody Guthrie. The entire song is about the beauty of walking the American landscape. He passes the California redwood forest and the Gulf of Mexico, fields of waving grain and shimmering deserts, and then there comes this verse

“As I went walking I saw a sign there

And on the sign it said “No Trespassing.”

But on the other side it didn’t say nothing,

That side was made for you and me.”

No clearer message of a person who wants to roam freely.

You’re right…that verse (which I had forgotten) fits perfectly!

Thanks, that’s what sprang to my mind, also.

Love the show.

When I moved from England/Wales to Scotland 25+ years ago the lack of red lines (foot paths and bridleways that were rights of way) on the maps was one on the first things to make me realise this really was a different country. There were no rights of way on official maps because you could go anywhere. It actually felt uncomfortable. Then it was codified in law just as I was getting used to the notion.

It does beg the question about the USA though. What exactly does “Land of the Free” mean?

Some photos of stiles I have encountered over the years:

http://stilesoftheisles.blogspot.com/

I was dealing with an impressive amount of cognitive dissonance listening to this. I have seen many examples of government-owned land in the US that is closed to the public. We have undeveloped spaces in San Diego owned by F&G among others that do not allow people to enter them. Also, you cannot be in a state park after dusk. Also, all trail building must be approved. In addition, mountain bikers are forbidden from a lot of public land by the current WIlderness Trails Act.

Accessibility is a hot topic for mountain bikers. Many sides, many opinions.

Having mentioned first Scandinavian right-to-roam laws and then the Scottish bothies I was surprised to not hear about the Swedish (and our neighbors too I would bet) right to camp pretty much anywhere in nature we want to.

There are of course exceptions such as nature reserves, national parks, crop fields or pastures etc. and areas designated for specific uses such as around running tracks. But any area not near someones house is free game for a person or small group to pitch their tents and make a camp site freely for a few days. You can pack the family and drive out to the woods and walk a bit and just set up camp for a weekend of camping, swimming and nature walks.

Of course there are rules to clean up after yourself and not cause unnecessary damage to the nature around you but in general it comes down to respecting the natural environment.

It’s a pretty great thing we have going.

We have that in Scotland too, something we’re very proud and protective of; https://www.outdooraccess-scotland.scot/Practical-guide/public/camping

I lived in Scotland and it was hard to understand the concept of the bothy. A friend showed me maids but even the type of location they used was a bit alien to me – I’m Brazilian and struggle with the whole miles / feet thing, but their maps used an even weirder location system.

In Italy they call this kind of place it “rifugio”. Little frugal huts usually in the mountains.

In August 02017 I spent my birthday in one up on the Etna volcano. I met some local Couchsurfers and we went there to spend the night and watch shooting stars. Amazing experience.

This is the one we stayed:

Bivacco Galvarina

95031 Adrano, Province of Catania, Italy

https://goo.gl/maps/kWmwDt5XnKK2

It is made out of the black vulcanic rocks you see all over this area in Sicily. The city of Catania is famous for these black rocks too.

Like so many of your stories, I enjoyed this episode and its sentiments. I can see that just talking about ‘right to roam’ when describing walking across England simplified things and helped with imagining the same access in the US.

Katie and Jim will know that (outside the National Parks), the 7% of English ‘open access land’ on which you can roam is relatively tricky to identify and very unevenly spread. In my corner of rural Dorset there are just small pockets here and there, which you can find on a rather clunky website.

Instead, 99% of the time, everyone and their dogs follow the umpteen thousand, mapped, signed, often ancient, lovely, footpaths and bridleways which criss-cross public and private land. These were mentioned only in passing.

Public footpath kissing gates and stiles are not really connected to ‘right to roam’ … you just wanted to bolt in ‘kissing gates’, didn’t you.

It’s just one of those moments when you are familiar with a subject, and what’s being said sounds a bit selective, perhaps to fit the narrative.

Don’t mind me – keep up the good work.

Stiles and kissing gates are pieces of infrastructure well designed to meet the potentially-conflicting needs of walkers and property owners: they let walkers through, but not cars or livestock. They do their job 99 percent invisibly :-)

I disagree with the commenter who characterized right to roam as socialist. The history of the concept goes back to feudalism, as non-socialist a social system as it is possible to be. Land ownership was more about the right to harvest fruit and wood, and even then, the general public were legally entitled to pick up fallen fruit and wood off a property owner’s land. The modern American concept of real estate as private property like a cellphone or a house, something you can bar anyone you like from accessing in any way at your own discretion, is new even in America.

Interesting episode, which highlights the distinct differences between the socialist leaning European/Asian continent, and the American cultural perspective of property rights. Not sure what this has to do with design though. I know I wouldn’t want “ramblers” crossing or camping on my ten acres. And as for design, maybe more of a focus on the design and architecture variations of the bothies would have been truer to the intent of 99pi.

I came to Tasmania from Scotland four years ago. They think like you here. It’s utterly dispiriting. Even the remant palawa (aboriginal) people, who suffered genocide under colonial rule after tens of thousands of years of living here, can’t easily visit some of their sacred sites as fifth and sixth generation Brit settlers won’t allow it. My interests by comparison are trivial, but very important to me.

Vermont has a right to roam for hunters. Carry a small slingshot and you’re a hunter, but there is no problem with pedestrian access if the land in not ‘posted’. Most problems are associated with off-road vehicles.

https://vtfishandwildlife.hosted.civiclive.com/cms/One.aspx?portalId=73163&pageId=6003732

Hawaii is in the US, and it has enshrined the right to move through private lands in the mountains, and furthermore harvest mountain resources in the native Hawaiian tradition. Furthermore all beach land is public property— it cannot be owned, and beachfront property owners must build and maintain paths for public access to their beaches to grade of regulations.

As I listened to this episode, and thought about the cultural differences between the UK (and other areas that are supportive of “rambling”) and the US, the one word that kept coming to mind was “litigation”. Here in the US, sooner or later someone would fall and break a leg and sue the property owner, and win a large settlement, and that would be the end of Right To Roam. Or, say, a small campfire, insufficiently extinguished, gets out of control and burns down a neighbor’s barn. Who’s responsible, the ramblers or the property owner who allowed them there?

More generally, the concept relies on a social compact that is, I think, stronger in some cultures than others. A assumption that users of a property will act responsibly and respectfully.

And finally there’s an aspect of scale, right? A property owner who might be fine with occasional parties of half a dozen rambling across a distant meadow might be less agreeable when it looks like Woodstock :)

Loved this episode! It brought back childhood memories of Sunday walks with my dad through the neighboring farms of Abbots Langley. I’ve been living in Texas for 15 years but I still remember the routes, the sounds and smells, and how excited I was to climb over the stiles.

There was a band in Ireland in the 70’s that my parents inflicted on me called “The Bothy Band”, and they had many songs about gypsies and ramblers. [Some of these terms have become a little fraught since then and the polite term now is traveller.] My dad being Irish assumed a right to pass through his land in upstate New York – he had 125 acres of former dairy farm when he retired. Culturally that’s generally an assumption in Ireland – I was walking with my cousin across fields in Claire a month ago and she said it’s generally assumed you can do it as long as you remember to close gates behind you. On the other hand, I talked to my father-in-law from Seneca Falls and he said the same generally applied when he was a kid, and this really started changing culturally in the 70’s.

No discussion of the “right to roam” is complete without also mentioning the “tragedy of the commons,” which is something we’re dealing with in many parts of the US, thanks in large part to people abusing wild public lands with off-road vehicles. In the New Jersey Pine Barrens, we have a huge problem with sensitive habitat for very rare species of amphibians and plants being destroyed in a single afternoon by destructive “jeep jamborees” that are organized on chat rooms online and attract many people from out of state who proceed to defy state law once they get here. Unfortunately, enforcement in many areas has been hamstrung by state budget cuts, as well as local law enforcement being unwilling to enforce existing laws.

I agree with the idea of “right to roam” in theory, but it’s a far more complex issue in practice. I’ve seen what happens when public lands in densely populated areas are wide open to abuse: conservationists have a hard enough time protecting the last strongholds of wild lands in these developed areas without a significant portion of the public abusing them with impunity, simply because they feel entitled to do so.

Great episode! I think you guys could have done more homework in Vermont though. We have a land/private property rights system that is heavily in favor of the walker or hunter. All land is legally accessible for everyone unless it is posted in a very specific way: Signs every fifty feet around the entire property that are not only signed and dated yearly but also registered with the town clerk. This is a hard process to achieve leaving most of Vermont land accessible to everyone as long as they keep things civilized, which most people do; most likely because we do share a sense of collective ownership beyond the private property aspect.

I’ve stayed in a couple of Bothies in the UK and they are spartan but perfect. If you’re struggling to imagine what they are like the think of the film ‘Withnail and I’ and then take away the home comforts. In fact one I stayed in is in the same valley. They are perfect when the weather is against you and a warm fire will dry you off.

There are still people who don’t want the right to roam. Some of our local farmers will make it clear you’re not wanted. Especially when it’s lambing season. It’s all about taking responsibility for your freedom to roam

I’m an American living in Scotland for 20 years now, and I love this show enough to offer a short criticism. Approaching this subject as if you were talking about Britain when you really are talking about England, given especially the reference to “other European countries” including Scotland, is a little perplexing. It would be such a problem if it were only once, but the fact is Americans all too often misrepresent England AS Britain (it’s a bad example, but Trump exemplified the tendency https://news.sky.com/video/donald-trumps-great-respect-for-uk-britain-england-11458849). Even though legislation was not introduced until roughly the same time as England, Scotland’s people had long had a much more generous attitude about the right to access the countryside. Now that’s enshrined in law, along with the Scottish Outdoor Access Code, which outlines the responsibilities people have to respect the rights of landowners.

I do love the idea of rights to land access in the USA, but I’m afraid that such a good idea would never catch on in the face of a raging retrogressive right wing, screaming ‘socialism!’ at the top of their lungs. All the things everyone worried about in England (glue sniffing fornicators and the like) would be amplified 100x in the states.

For my take on walking in Scotland, check out my blog entry ‘Walking in the Land of the Free’ http://www.drewhammondmusic.com/blog/walking-in-the-land-of-the-free.

I think its very interesting that there is an Icelandic word, “Ramba – Ganga án markmiðs” or Ramba “to walk without a meaning/goal”.

Ramba is also pronounced “Rambla” sometimes.

So its an old scandinavia word :)

The Right to Roam (and the tens of thousands of unrelated “Public Rights of Way”) are one of the best things about the UK (and other places with similar laws). Having moved to Australia, hiking is a much more prescribed affair – you drive to the state park, park in the official carpark and then hike one of a handful of marked trails. There’s also little of the human geography which make walks in the UK often so interesting. Near where I grew up, a typical hike might include passing Victorian mills, working farms, follies and monuments, the grounds of stately homes, army assault courses, riding stables, canal towpaths, drinking water reservoirs and windfarms (you can walk right up to the base, really surreal experience), all of which would be fenced off as private land over here. Plus you get to have a pint and a nice lunch at a country pub half way along. Don’t get me wrong, wilderness is great to hike through, but it’s sad that the options are so limited.