The state of Utah has about three million people, and a third of them live in one valley—surrounded on three sides by 7,000 foot mountains, and to the north by a great big salty lake. The valley is home to the state capital, Salt Lake City, and a bunch of other small cities and towns that, over time, have grown together, into one big mass.

One of the towns amid the sprawl is Midvale, which is home to the Applewood mobile home community for seniors. Applewood has just over 50 lots spanning around seven acres of land, and it looks a lot like the surrounding suburbs, but denser and with smaller homes.

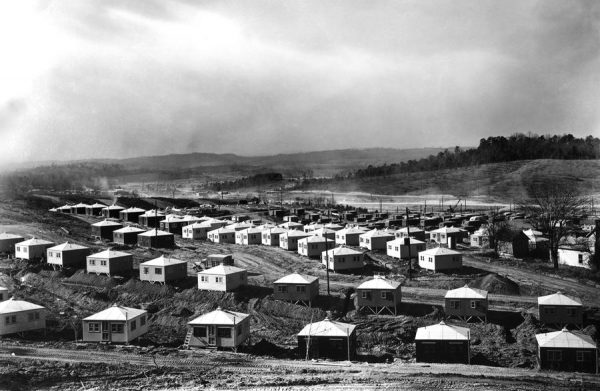

They may look modest, but many of the houses are well-constructed and, on the inside, they can be quite spacious and defy reductive stereotypes. Resident Shirlene Stoven says visitors are often surprised by her space, and also argues that her “manufactured home … is built stronger and better than 90 percent of these little tract homes that you find” (like those in the images below).

Mobile homes don’t get a lot of love in our culture, despite being a key source of affordable housing stock in the United States. Throughout the 1990s, 66% of new affordable housing built was mobile homes. Shirline, a divorcee with grown children, bought her place in 1994, and was excited to buy a home of her own rather than paying rent.

Halfway Home Ownership

But when you buy a manufactured home, the structure itself is only half of the equation. Then you need to find a place to put it. And Shirlene found what seemed like the perfect spot. A small, quiet mobile home park with an empty lot.

But there was a problem: the same dynamic that made this housing situation affordable for Shirlene also left her vulnerable, because the mobile home was hers, but the land underneath it wasn’t.

“Part of the paradox at the heart of manufactured housing,” explains Esther Sullivan, a sociologist at the University of Colorado Denver “is that it’s precisely the thing that makes it so affordable that also makes this a highly insecure form of housing.” She says that about a third of mobile homeowners live in parks like Applewood where they rent a plot of land for their home. She calls this arrangement halfway homeownership, because it’s filled with uncertainty. The property owners can raise rents, or fail to maintain communal infrastructure, or even sell the park and evict everyone living in it. Often there isn’t a lot that residents can do.

“Part of the paradox at the heart of manufactured housing,” explains Esther Sullivan, a sociologist at the University of Colorado Denver “is that it’s precisely the thing that makes it so affordable that also makes this a highly insecure form of housing.” She says that about a third of mobile homeowners live in parks like Applewood where they rent a plot of land for their home. She calls this arrangement halfway homeownership, because it’s filled with uncertainty. The property owners can raise rents, or fail to maintain communal infrastructure, or even sell the park and evict everyone living in it. Often there isn’t a lot that residents can do.

For decades, the owner of Applewood took care of the park, and kept rents low and affordable. But in 2011 he got sick and sold the property. And one day the new owners informed the residents that rent was going to go up significantly, from $320 to $460 over the course of the next year. Then residents learned that they were planning to build an apartment complex right on top of the park. Since the residents didn’t own the land beneath their homes, there wasn’t much they could do to prevent eviction.

Trailer Tropes & Dreams

To understand how mobile home owners ended up in the precarious position of owning a home without land, one has to look at the early 20th century and the dawn of the automobile age. “People had cars for the first time,” explains Andrew Hurley, a history professor at the University of Missouri, St. Louis, “and could go out and explore America in a cost-effective way by attaching a little trailer to the backs of their Model Ts.”

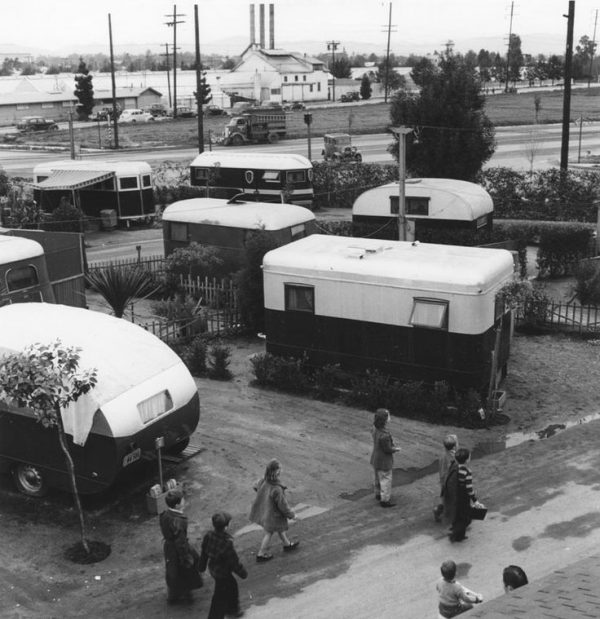

At first these “tin can tourists” were relatively wealthy, but then came the Great Depression, when migrant workers started living in trailers full-time as they traveled the country looking for work. These mobile home dwellers began setting up parks, which writings from the time period often referred to as slums. This was the beginning of the classist trailer stigma that is still around today.

But the event that really solidified the trailer as a viable form of American housing was World War Two. As the conflict got underway, factories popped up in all of these remote parts of the country, and the government bought trailers to house the wartime workforce.

This was supposed to be a temporary solution. When the war ended, the expectation was that people would move back into conventional homes, but that didn’t happen. Instead, trailers remained an affordable housing option for people who didn’t have the money to buy a home in the expanding suburbs. As the government slowed down its investment into affordable housing, mobile home parks spread.

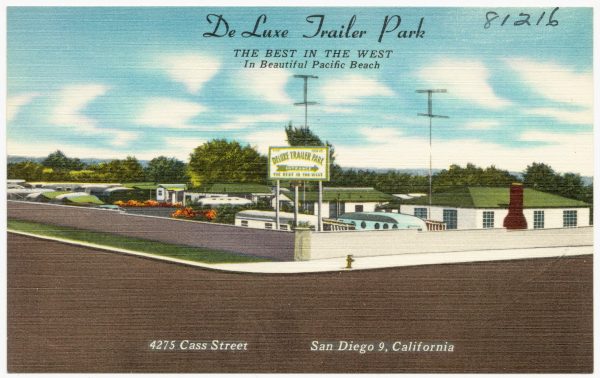

Through it all, mobile homes were never able to shake off the stigma that began during the Great Depression. People just did not want mobile home parks built in their backyard — and cities used all the tools in the urban planning toolkit to render mobile home parks invisible, sometimes requiring them to be walled off or screened from sight.

Often, these parks were located on marginal land on the outskirts of cities. Because mobile homes were legally classified as a form of transportation rather than housing, they could be built on substandard land that wasn’t zoned residential — separated from ordinary residences, they wound up in commercial and industrial zones. But as cities expand, that land has become more valuable, and increasingly the target of redevelopment plans.

Saving Applewood

Most people think of “mobile home parks” as being full of, well, “mobile” homes, but today most manufactured houses really aren’t made to be moved around a lot. Trailers and RVs are one thing, but manufactured housing is made to be moved to a site, set down and lived in. The manufactured homes in a park like Applewood are more like conventional single-family homes than travel trailers. Today, the term “mobile home” is more or less a misnomer. Actually moving a modern manufactured home can cost thousands of dollars and risks serious structural damage to the home. Even if Applewood residents were willing to pay that price and take that risk, finding a new location would be extremely challenging.

Shirlene Stoven says that if she got evicted, she would probably have to abandon her home and move in with one of her kids, and that just isn’t an option for some residents. She began organizing residents and rallying support to protect Applewood, arguing to the mayor and city council on behalf of herself and her neighbors.

Shirlene and the other residents of Applewood fought for several years to stay in their homes. There were a lot of twists and turns, late nights and a whole lot of emails, but eventually, after a lot of public pressure, the development company gave up on the project, and decided to put Applewood up for sale, so Shirlene called ROC USA.

“R O C stands for resident-owned communities,” explains Paul Bradley, the President of ROC USA, “and we help homeowners in mobile home parks buy their communities as a co-op.” Bradley has been organizing mobile home co-ops since the 1980s. In New Hampshire, where ROC is based, they even got legislation passed that gives mobile home owners a first option to purchase the land whenever a park goes up for sale. Today, over 25% of mobile home parks in the state are resident-owned.

Paul Bradley says that we need to build more affordable housing in this country, but he also wants to protect the affordable housing that we already have. Right now, mobile homes represent the largest source of unsubsidized affordable housing produced in the U.S. If we can help mobile home owners buy the land beneath their parks, then the risk of mass eviction disappears. So in 2008, Bradley launched ROC USA in an effort to spread New Hampshire’s cooperative ownership model nationwide — so far, they’ve been really successful, creating a network of over 220 communities and 14,000 homeowners in 15 states.

When Shirlene called Paul Bradley, things were not looking great for Applewood — the land had already been sold to two new developers for $4.8 million. But Shirlene and Paul approached the new owners and explained the situation. They talked about how difficult it would be to move their homes and asked if the new owners would be willing to sell the park to the residents. The new owners said that if the residents could come up with five million dollars than they would sell them the park. Individually, of course, no one living in Applewood could get a loan for that amount of money, but together, it was a different story. ROC USA was willing to give the residents a very low interest loan for $3.6 million. They also got funding from a low-income housing firm in Utah called the Olene Walker Fund.

Now, after four years of fighting for their little piece of ground, the land officially belongs to the Applewood Homeowners Cooperative. To pay off their collective mortgage, the residents agreed to pay $60 more per month than they had previously been paying in rent. That’s going to be a challenge for some of them. But the monthly costs should be stable from here on out, and they’ll no longer need to worry about eviction.

And they aren’t on their own anymore, either. ROC USA is helping them structure the co-op and deal with finances. And of course, a co-operative Applewood means cooperative living. There are lots of meetings and elections and committees, but they have an advantage: they have been a community for a long time. The co-op is going to be a lot of work, but at least for now, people are glad to be a part of it — and to finally own the land under their homes, together.

Comments (15)

Share

The owner of the property has every right to sell their land, the people leasing the land are doing just that, leasing. The fact that they stopped the owner from selling the land or developing the land as they pleased is wrong. It is sad that these people would have to relocate but that is a risk you accept when you rent.

The owner had an investment that was artificially and unjustly blocked. The true value of the land was likely far from the sell price they ended up receiving.

Actually, the Applewood property was resold for about the same price to the residents as it initially was to the developer. And there was no blocking or forcing.

“But that is a risk you accept when you rent”

Yes, but it seems some people do not have any other option other than to rent.

I agree with Sam that the property owner has the right to own or sell, and to modify rental prices as the market allows. This is one of the fundamentals in a free market, which the tenants of these spaces agreed to when they signed a contract to rent a space in the park. “The system of private property is the most important guarantee of freedom, not only for those who own property, but scarcely less for those who do not”, Friedrick Hayek.

While the communal purchase of the park is a novel idea, given that the residents are generally on a fixed income, as prices increase they are less likely to be able to increase their revenue stream, and will most likely fall short of costs for maintenance, infrastructure repairs, and other communal commodities within the park. They will then be in the same situation as the previous land owner, and will need to raise rent prices. Checking back with this group in five years and seeing how they’re doing would be an interesting follow-up.

Roman, you missed an opportunity talk about design (both good and bad) of mobile homes and manufactured housing and how it has helped and hindered affordable housing and habitability. I do wish that 99% would go back to its roots, focus more on design, and less on the SJW perspective. It was so much more better in the beginning episodes than the last few years.

Another term used for mobile homes is park models. I’m wondering if this is a term that is only used in Canada? Seems like a more appropriate name…

Also, one of the issues with mobile home parks is the declining infrastructure. In some places, the underground infrastructure was built under the homes, so fixing it involves moving structures that are no longer easy to move. It becomes a very challenging problem for both the homeowner and the land owner. I wonder how much the co-ops know about the infrastructure under their land and what future of reparation costs might mean?

Hi Karen,

Park models are built to the RV code. Manufactured housing is built to the HUD-code. The latter is intended for full-time and long-term occupancy and while some people do live in park models and RVs full-time, they’re not designed for it.

In terms of co-ops and infrastructure, every co-op we work with hires and civil engineer who inspects the systems and develops a 10 year Capital Improvement Plan on which their reserve deposits are budgeted. Getting the CIP right is one of the key elements in the due diligence process.

Insuring a manufactured/mobile/trailer home is more expensive than a conventional property, so keep it in mind if you are considering purchasing one.

One of the other oddities about mobile homes is that while the homes themselves are less expensive (selling price), the loans people use to pay for them can be more expensive (interest rates/loan terms). Because mobile homes are often titled as “personal” property (moveable) as opposed to “real” property (land/buildings) they fall outside the scope of many of the subsidized housing/housing finance programs people might otherwise be eligible for. And worse loan terms can have a big impact when it comes to securing an affordable monthly payment.

Luckily there are policy initiatives being developed nationally (right now) to better serve these communities. See the Federal Housing Finance Agency’s, Duty to Serve guidance, Manufactured Housing initiatives- https://www.fhfa.gov/PolicyProgramsResearch/Programs/Pages/Duty-to-Serve.aspx

Hopefully these programs will provide more affordable financing for individual mobile home borrowers and for mobile home communities (so it’s easier for ROCs to gather the funding needed to purchase and save their communities).

Great work, as always, 99pi !

Great episode.

I live in Goshen Indiana, which claims to be “mobile home (or rv or manufactured housing) capital of the world” because so many rvs are made here. Neighboring Elkhart even has the RV Hall of Fame. I am not making this up.

My question is why isn’t this a problem for the manufacturers? Seems like it would be their best interest to help their customers solve this problem. But wait, I’ve seen how they operate and I already know the answer.

I Lived in a park about a couple miles from applewood. Developers bought the land evicted everybody, it was called the meadows on creek road. You cannot attribute risk valuation with rent when there are not enough affordable homes in a place to live. What really ends up happening, is that the most marginalized people are taken advantage of for being lucky enough to live in “not a slum” that can be bought and sold to someone who’s money is more valuable. Where I used to live has 4 million dollar house on it now and my daughters friend was just shot next to the park where I was forced to live.

I know that this episode was about a really great story of people who found a way, but most dont. It was only possible because of the personal charity of the developers who bought the land. That is an outlier and is not “design”.

If 99% of people get evicted by design that is the story, not the 1% who found charity. I’m really sorry I love your show, but you picked low hanging fruit on this one. You didn’t talk to SLC CAP or the director of housing authority, or talk to anybody who suffered fall out from a closure of a park.

Casey, I’m really sorry you didn’t have the opportunity to buy your park, but what happened with the folks at Applewood wasn’t charity. The developers got their $5 million price. ROC USA is working to change the “design” of evictions by making financing and technical assistance available to groups of residents so they can save their homes and communities.

There’s an excellent edition of the New Economics Foundation podcast which is a good companion to this episode, which looks at bringing down house prices, without causing huge problems for an economy largely predicated on them going up.

http://neweconomics.org/2018/03/can-we-bring-down-house-prices/

Over listening to the end story, I was reminded of a company called Kasita around the Austin area. It’s a current concept for mobile living and interchangeable urban stacks. Their design definitely wins over the Ready Player One imagery but still very reminiscent of the Emmert’s idea.

Terrific reporting. Thank you!

The resident-owned community (ROC) movement is an important factor on preserving affordable workforce housing. It could become exponentially more so if legislatures can be persuaded to title these homes as real property, as Jacob notes.

To address John’s thoughts above on the resilience of manufactured-home communities, the New Hampshire Community Loan Fund converted its first park in 1984. There are now 124 in the state, containing more than 7,000 homes, and not one community has failed.

Homeowners in the co-ops continue to pay rent, but the rent goes to the cooperative (as opposed to profits for owners and shareholders) and is invested back into the community. Homeowners in our earliest co-ops now pay pay extremely low rents, and have been able to improve, then maintain, their infrastructure.

My brother recommended I might like this website. He was entirely right.