In the late 1920s, the Ford Motor Company bought up millions of acres of land in Brazil. They loaded boats with machinery and supplies, and shipped them deep into the Amazon rainforest. Workers cut down trees and cleared the land and then they built a rubber plantation in the middle of one of the wildest places on earth.

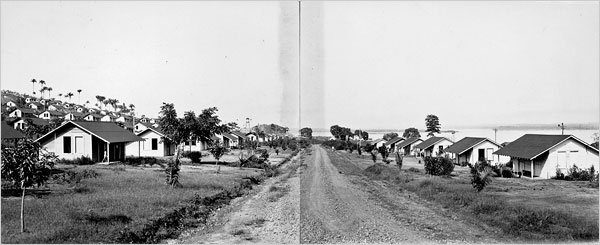

The plan was to harvest the rubber and ship it back to Detroit, where it would be turned into tires and other parts for Ford cars. But Henry Ford wanted this community — called “Fordlândia” — to be more than just a huge plantation. He envisioned an industrial utopia. He paid his Brazilian workers good wages, at least for the region. And he tried to build them the kind of place he would’ve loved to live, which is to say: a small Midwestern town … but in the middle of the jungle. It would have its own power plant, electric lighting and phones, a hospital, sawmill, church, and a processing plant for rubber.

“He wanted to create this village for the workers down in Fordlândia, explains Roger Weber, host of the podcast Mismatch. “And while it’s easy to look at him as some greedy imperialist capitalist,” — which he was as well — “he actually felt that he could help these people.” The company hospital, for instance, would provide free medical care to employees and nice lunches would be served each day at work.

In the end, though, the project would prove to be a colossal, expensive, and tragic mistake, though it took Henry Ford nearly two decades to give up on it. “It’s a parable of arrogance, but the arrogance isn’t that Ford thought he could tame and conquer the Amazon,” says historian Greg Grandin. “He had his sights on something actually much bigger. He thought he could tame and conquer capitalism, industrial capitalism. That didn’t happen.”

Tapping Rubber

In the early 1900s — a few decades before Ford set out to build Fordlândia — a massive shift was underway in the rubber industry. Historically, Brazil had been the world’s main supplier of rubber, and the way rubber was cultivated was very labor-intensive. Rubber tappers would go out into the dense jungle and find rubber trees. They would slash the trees and extract the latex that flowed out on them, then boil this milky fluid and turn it into large balls of rubber to sell. It was a decentralized process, but this rubber would eventually wind up in manufacturing warehouses. The tappers, meanwhile, would do their work for part of the year, then grow subsistence crops for the rest.

But this economy could be brutal for workers at the bottom of the production chain. As rubber plantations grew, they struggled to find enough workers. Some rubber barons started enslaving indigenous people and forcing them to tap the trees. Even the workers that were being paid, didn’t make very much. The so-called “latex lords” at the top grew enormously wealthy, living in palatial homes in gilded jungle cities.

This system all started to change because of a British explorer named Henry Wickham, who had come to Brazil to seek his fortune in the Amazon. In 1876, he stole thousands of rubber plant seeds, which he then shipped to England.

This system all started to change because of a British explorer named Henry Wickham, who had come to Brazil to seek his fortune in the Amazon. In 1876, he stole thousands of rubber plant seeds, which he then shipped to England.

There was technically no law at the time preventing the export of the seeds, but Wickham had applied for an export license under false pretenses. He smuggled the tens of thousands of seeds back to England in the hold of a steam ship. Each seed was about three-quarters of an inch long. His entire seed cache weighed over 1,000 pounds. And he may not have known it at the time, but this act of biopiracy would totally transform the global rubber trade.

From England, Wickham’s rubber seeds traveled to various European colonies like Malaysia, Sri Lanka, and Indonesia. The trees thrived in these warm tropical environments, where no blight or bugs had evolved to eat them. Growers set up plantations with rubber trees planted in dense rows. These new colonial plantations massively outperformed the traditional Brazilian rubber tappers, and Brazil effectively lost its grip over the market by the early 1900s.

From England, Wickham’s rubber seeds traveled to various European colonies like Malaysia, Sri Lanka, and Indonesia. The trees thrived in these warm tropical environments, where no blight or bugs had evolved to eat them. Growers set up plantations with rubber trees planted in dense rows. These new colonial plantations massively outperformed the traditional Brazilian rubber tappers, and Brazil effectively lost its grip over the market by the early 1900s.

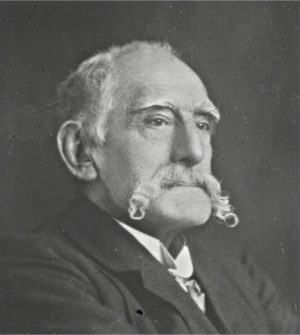

Meanwhile, the new European rubber barons were talking about setting up a kind of cartel. They now dominated the global rubber trade, and they realized that meant they could set its prices. Which made a certain American industrialist named Henry Ford extremely nervous. “The Ford Motor Company in the 1920s pretty much controlled nearly every raw material that went into the making of a motor car,” says Grandin — “the glass, the iron, the wood, the lumber, everything except latex.” This looming European-controlled rubber cartel represented a big threat to Ford’s business interests. If rubber prices went up, it would make tires and gaskets and tubes more expensive.

So Ford wanted to create his own rubber supply — unfortunately for him, rubber doesn’t grow in the United States. And Brazil, eager to get back into the game, was happy to provide him with two million acres to create a rubber plantation. If anyone could make it work, they thought, it would be Henry Ford. But “it was a boondoggle from the very beginning,” says Weber.

Jungle Urbanism

The Ford company shipped in supplies on the Tapajos River, brought in American managers, and hired a Brazilian workforce. Then they started clearing the land to build Fordlândia, but things started to go wrong very quickly. Shirtless workers clearing the land were attacked by ants, hornets, scorpions, and deadly pit vipers.

Eventually, the workers managed to clear the land and to build a town in the middle of the rainforest. And Ford had a very particular vision for this town. He wanted it to feel like the small Midwestern towns he associated with his childhood. “He grew up on a farm,” explains Weber, and “believed that there was a kind of healthy connection between between agriculture and industry.”

His nostalgia was for a very narrow slice of America — small-town, mostly white America. (Ford was well-known for his racist and anti-semitic views). But that was Ford’s model for Fordlândia, even though he was importing it to a very different cultural environment. “When you go to Fordlândia,” says Grandin, “there’s an uncanniness to it, a familiarity. It doesn’t seem exotic. It seemed very recognizable.”

The company then set up plantation-style rubber fields with lots of densely planted trees, in the style of the colonial rubber tree plantations in Southeast Asia. They started recruiting even more Brazilian workers from the surrounding areas, and a lot of them were excited to work for Ford. He was promising them things they had never really had, like free healthcare and education.

And Ford wasn’t just being benevolent — he was being strategic. Back in the U.S., he’d discovered that if he paid his workers well and let them work reasonable hours — if he didn’t totally exploit them, in other words — then he could dramatically reduce turnover. He thought he could take lessons learned from his factories and apply them to this new plantation. He aimed to “run a plantation in South America as though it were an industrial facility here in the Midwest,” explains Matt Anderson of the Henry Ford Museum, complete with time clocks and eight-hour shifts.

Cultural Climate

In implementing his vision, Ford faced cultural and climactic obstacles. People in Brazil were, for instance, used to working in the early morning, then taking a break during the hottest parts of the day, and later coming back to work. This didn’t fit with Ford’s ideal nine-to-five workday. Also, back in the States, Ford had created an industrial system where workers could actually afford to buy the products they made, but in the Amazon there wasn’t that much to buy. “There was no consumer society within the Amazon so they didn’t actually need the high wages that Ford was promising,” Grandin elaborates. So “they would work a few weeks or a few months and then they would disappear and … go back into the jungle to work their plots, to produce their own food, and maybe they come back the following year, and this would drive the Ford managers mad.” Ford’s turnover-reducing strategies didn’t work in Amazon like they had in Detroit.

The cultural disconnect went beyond work culture. Henry Ford had very particular ideas about how a society should be arranged and what people should enjoy. For example: he loved square dancing. He had met his wife Clara at a square dance, and decided to have a big dance hall built in Fordlândia. But it wasn’t as popular as he expected.

Ford was also a teetotaler, so even though drinking was legal in Brazil, he prohibited alcohol in Fordlândia. This also failed. Some savvy entrepreneurs set up a bar and a brothel on a little island near Fordlândia and called it “The Island of Innocence.”

Food became an issue, too. Ford was a vegetarian and an early advocate of healthy eating, but pushing his preferences on his workers led to a riot. In 1930, employees already resentful of these dietary impositions were appalled at a shift from restaurant-style lunch service to a cafeteria-style self-service system (designed to be more efficient). They began rioting, and ended up destroying much of the town, including the time clocks, which were smashed to pieces. Managers fled on boats. Eventually, the town was retaken with the help of Brazilian security forces. Instead of giving up on his failing project, Ford doubled down, pouring more money in to try and make it work.

Ford’s Focus

Ford was only a few years into this Fordlândia experiment and it wasn’t paying off. But the company always seemed to have a way to justify the project. “In the 1920s, it was going to be a symbol of what industrial capitalism could bring to the backwater of the Amazon,” says Grandin. “In the 1930s, during the Depression, it [became] a symbol of how to survive the downturn.” And, of course, no one wanted to tell Ford it was a bad idea. He was rich and successful, but also stubborn and set in his ways.

But Fordlândia was up against insurmountable challenges. More than time clocks, square-dancing, and meal service, the real problem was the insects and fungi that were the rubber trees’ natural predators in the Amazon. Ford hadn’t bothered to learn anything about botany or agronomy before embarking on his Fordlândia experiment. He didn’t trust the kinds of experts that could’ve warned him what he was getting into. In fact, he didn’t trust experts at all — he was a figure-it-out type, skeptical of fancy educations and titles. “That was part of the problem,” says Anderson, “thinking that he could just go down there and take this raw jungle and turn it into an industrial enterprise. His ambitions got ahead of his abilities in this case.”

But Fordlândia was up against insurmountable challenges. More than time clocks, square-dancing, and meal service, the real problem was the insects and fungi that were the rubber trees’ natural predators in the Amazon. Ford hadn’t bothered to learn anything about botany or agronomy before embarking on his Fordlândia experiment. He didn’t trust the kinds of experts that could’ve warned him what he was getting into. In fact, he didn’t trust experts at all — he was a figure-it-out type, skeptical of fancy educations and titles. “That was part of the problem,” says Anderson, “thinking that he could just go down there and take this raw jungle and turn it into an industrial enterprise. His ambitions got ahead of his abilities in this case.”

Rubber trees had never been grown in the Amazon in the way that the Ford company was trying to grow them: in dense plantations, with trees planted in tight rows. This growing style might have worked in the Southeast Asian plantations run by the Europeans, but that’s because the bugs there hadn’t evolved to eat rubber. In Brazil, this density ended up creating an environment where the native bugs that fed on rubber trees thrived. Basically, Ford built a giant bug incubator, where close proximity helped pests and blight spread.

Rubber trees had never been grown in the Amazon in the way that the Ford company was trying to grow them: in dense plantations, with trees planted in tight rows. This growing style might have worked in the Southeast Asian plantations run by the Europeans, but that’s because the bugs there hadn’t evolved to eat rubber. In Brazil, this density ended up creating an environment where the native bugs that fed on rubber trees thrived. Basically, Ford built a giant bug incubator, where close proximity helped pests and blight spread.

Sometimes, worker efforts to address these problems just made them worse. There was one species of caterpillar, for instance, that would usually eat leaves from the bottom, where they were visible. Workers would pick these off and pile them into bonfires. But within a few years, the caterpillars had adapted, eating the leaves from the top instead, where workers couldn’t see them. Again and again, they re-planted the trees, only to have them killed off by pests. This went on for years, devastating the plantation.

Remote Control

It wasn’t until 1945 that Ford finally decided to shut down Fordlândia. At that point, Henry Ford had turned the company over to his grandson, and Fordlândia with it. Within a few months, the land was sold back to the Brazilian government for a few hundred thousand dollars. Henry Ford died a few years later. Strangely enough, despite all of the time and money he invested in Fordlândia, he never actually went to visit it himself. He had orchestrated the whole fiasco from his home, thousands of miles away, in Michigan.

Fordlândia is still a town today. Although a lot of the old buildings are now falling down, people continue to live there. Historian Greg Grandin has visited twice (two times more than Henry Ford ever did, for those of you keeping count). He made his way up the Tapajos river by boat, a trek that takes a day and a half.

“You just come around the bank and then all of a sudden you see this enormous water tank,” Grandin recalls. “Back in the day, the word ‘Ford’ was written on the water tank and you could see the outlines of what was ‘Fordlândia’ …. It’s now a regular town.” Since its collapse, “Brazilians have moved in and taken over all of the houses, but you still get a sense of what it looked like in the 1920s and 1930s.”

Some residents, like Ana Rita Souza (who runs the local hotel) make a living in part thanks to tourists who come to see what’s left of the place. But there aren’t many jobs left in the area for the two thousand inhabitants of Fordlândia — most of the economy in the region now revolves around industrial soybean production and cattle ranches.

Some travelers are here for the past — what’s left of Ford’s crazy vision, an American-style town in the middle of the Brazilian jungle, a culturally-insensitive and paternalistic “boondoggle” that (for all its faults) did manage to provide decent wages for its workers.

Souza, of course, wasn’t there to see all the ways Fordlândia went wrong. For her, the historic remains represent a time when this sleepy town was the focus of a massive experiment by a world-famous industrialist. Now, with its crumbling old buildings, Fordlândia is a different kind of lost civilization than you’d expect to find in the middle of the Amazon: a Midwestern fantasy-land returning to the jungle.

Comments (6)

Share

Wow, i live in Brazil and never had know about that.

Hello! When I saw the episode title populate in my podcast feed, I was excited by the opportunity to pair a story on Ford’s namesake utopia with an accompany album by the same title. I would bet 99pi listeners would appreciate the late composer (just passed away last month, way too soon) Johann Johannsson’s album Fordlandia. Listeners can find it on the usual services (Apple, Spotify, etc.)…

Ugh. Even a professor of constitutional law deifies the constitutional framers saying the open endedness was “genius”. It wasn’t genius. It was lazy and easy for the time. That sort of open endedness cannot work in today’s world. Legal “fuzziness” is not genius. Liberals have to start realizing that “founding fathers” would be considered stupid, greedy and racist if compared to today’s legal scholars and human rights activists.

because they were

Well, that’s just your opinion, man.

I am a citizen of the Metropolitan Detroit area and heard of this story on WDIV- so excited that my favorite podcast decided to cover it! There are a lot of Ford workers today from Brazil living in the Detroit area. I know many automative companies outsource, but I even wonder if they are aware of it.

It’s also nice to hear of what an eccentric and stubborn man Ford was. Around this area, he is praised. This story presents another dimension of Henry Ford.