Seen from above, Sofia, Bulgaria, looks less like a city and more like a forest. Large “interblock park” green spaces between big apartment structures are a defining characteristic of the city. They’re not so much “parks” in the formal sense, with fences and gates, just open green areas growing up in interstitial spaces left behind.

But as green as it still looks today, Sofia used to be even greener. Since the fall of Bulgarian communism in the late 1980s, Sofia has lost more than half of its green space. To understand why, one has to look back to how the city evolved and grew in the Soviet era.

The Bulgarian communist party came to power in 1946, when the city was home to just 400,000 people and was surrounded by farmland. The goal of Bulgaria’s new communist government was to transform Sofia into a modern industrial capital.

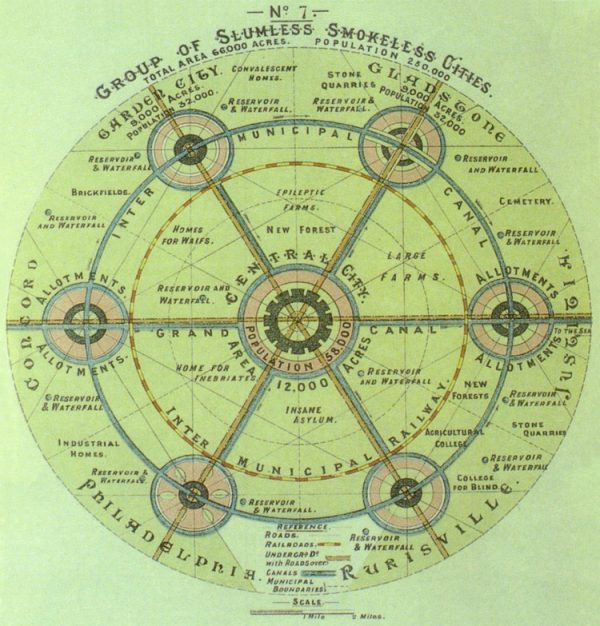

Inspired by Modernists like Le Corbusier, they planted tall buildings in seas of greenery, which they blended with idea from the Garden City movement about balancing urban and rural spaces. Garden Cities, politically, were meant to be shared in terms of ownership and administration, which fit neatly with the politics of the time and region.

Building a utopian city is hard if you have to work with what’s there, and much easier if you can raze history and build from scratch. Nationalization took many people away from the land their families had worked for generations. But it also cleared the way for Bulgaria to put the inspiration for a modern Garden City into action.

In the decades following the seizure of private land, Bulgarian city planners fundamentally transformed the landscape of Sofia. Where there was once farmland, a series of communist-planned neighborhoods fanned outwards from the city center. The earliest of these neighborhoods all tend to have a certain distinctive setup.

Surrounding all of this new infrastructure were Sofia’s interblock parks. They were seen as an important way to put the government’s communist ideals into action. Private spaces could be relatively small, because it was all about communal shared space, mainly outdoors.

Finally, in late 1989, the Bulgarian communist party reached the end of its long decline. In November the dictator Todor Zhivkov was forced out of office. And by December his replacement was calling for free elections. Bulgarian communism had fallen. And as the dust cleared, the interblock parks were the last thing on anyone’s mind.

In the wake of the fall, there were efforts to return land to prior owners. Of course, this rendered many parks essentially unusable. They were too fragmented to use and too hard to maintain. And in the end, many Bulgarians couldn’t afford not to sell. In late 1996 the Bulgarian economy collapsed and inflation soared. There were plenty of people looking to sell their lots… but there was really only one group of buyers wealthy enough for them to sell to: Bulgaria’s newly minted oligarchs.

Today the city has that bourgeois-fascist invention, the suburb. People put up fences and even mansions. In fact, Sofia residents have so thoroughly rejected the idea of public resources that many of those new mansions are actually on dirt roads: no one is funding the city to maintain that kind of shared infrastructure. But the pendulum always swings, and young people are looking at how things have gone in their lifetime, and wondering if they can’t bring back that Garden City ideal.

Leave a Comment

Share