Happy National Train Day, everyone – for those of you who missed it: that was May 13th this year. A year ago, we started down this path with Train Set: Track One, which gave way to Track Two …and now, here we are for the final part of our train-fecta.

First Stop: Shining Time Station

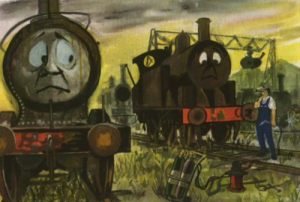

In the cartoon world inhabited by Thomas the Tank Engine and Friends, anthropomorphized trains chug chug chug along the picturesque countryside of this hilly, bright and colorful island. But something much darker lurked beneath the surface of this children’s show.

In some episodes you see sentient vehicles being murdered – crushed or ripped apart – dismembered, effectively – often for fairly minor slights or offenses. But one of the most vivid and horrifying examples is an episode called The Sad Story of Henry. It starts off whimsically enough with an engine named Henry who gets a spiffy new paint job and wants to shelter it from the rain as it dries.

In some episodes you see sentient vehicles being murdered – crushed or ripped apart – dismembered, effectively – often for fairly minor slights or offenses. But one of the most vivid and horrifying examples is an episode called The Sad Story of Henry. It starts off whimsically enough with an engine named Henry who gets a spiffy new paint job and wants to shelter it from the rain as it dries.

So Henry comes to a stop in this railway tunnel and refuses to move. Eventually, the big boss, Sir Topham Hatt, comes along and tries to push and pull Henry. He then declares that they will strip away the train tracks out from under Henry and brick off the tunnel … permanently. His fire slowly goes out, and he is left to wallow forever in an artificial purgatory for the crime of staying dry.

Warning: Torpedoes Away

Signaling an oncoming train to stop can be tricky — visual cues might get lost in the fog, and audible alerts have trouble piercing the noise of the trains themselves. So in the mid-1800s an English mechanical engineer decided to employee something new: explosives.

Trains were outfitted with sets of small “torpedoes” designed to be laid down on tracks behind them should they have to stop. Construction crews were also given these, in case other systems for diverting trains away from worksites failed. Remarkably, this relatively low-tech solution is still in circulation to this day — sometimes simple designs just work.

Short Stop: World Records

While a number of towns, cities, city-states, and nations around the world boast being home to the ‘world’s shortest train,’ it turns out the answer to lies not so much in the actual inches and feet of train track but in how key terms get defined – in this case, words like “short” and “nation.”

The good old Guinness Book of World Records lists the shortest train line by track length as the Fisherman’s Walk Cliff Railway funicular in Bournemouth, England. This wee railway is just 128 feet long. Meanwhile, the Vatican Railway – serving Vatican City would seem to be a very distant second at 4200 feet long – but they claim the title of the world’s shortest “national” railway- which makes sense because they’re the world’s smallest nation.

And in California, there’s Angels Flight, which operates on Bunker Hill in downtown Los Angeles. It’s nearly 300 feet long, just one city block, and the ride only takes only about a minute – which they argue makes it the ‘shortest’ train in terms of duration. But really, all (short) trains are good trains — it doesn’t have to be a competition!

All Aboard: Private Cars

A lot like the swank private planes of today, a private train car was historically just one of those things rich people could own — and many did. There’s this one car, for example, that was originally designed and built for Charles Schwab, the famous financial executive. It has elaborate woodwork, gas lighting, and multifunctional furniture among other amenities.

But private cars are not just a thing of the past — today, people still own private rail cars and pay Amtrak to park them and to tow them around the country on the backs of other trains. It’s not cheap, but for those who can afford it, it’s a luxurious way to ride the rails.

End of the Line: Slip Coaches

back in the mid-1800s, the Brits questioned that most fundamental function of trains: the need to stop them at stations. On some routes, they began using what are called “slip coaches” – cars that would be detached at speed then coast to a stop at a station.

Each slip coach car had a designated engineer – who would unhook the last car in the chain when approaching a target stop, then slowly bring it in for a landing. Meanwhile, the rest of train would continue on its journey. And this went on for decades. The last in-motion slip decoupling in Great Britain was as recent as 1960.

A number of things contributed to the abandonment of this design. For one thing, trains were getting faster, exacerbating the dangers. Also, slipping coaches was labor-intensive: each slipped car needed its own engineer. Plus, to make a slip coach work, passengers had to be locked in their individual components and couldn’t access dining cars – and if they got on the wrong car, well, they got to think long and hard about their mistake while stuck in that car, waiting to be slipped.

Leave a Comment

Share