On the west coast of Ireland, on the banks of an estuary dividing county Limerick from county Clare, lies a small town called Shannon. But Shannon is not a quaint fishing village or farming community. Its industry is its airport. And Shannon Airport is big. It handles up to 1.7 million passengers and 20,000 flights a year, most of them from other countries. It looks like a cosmopolitan international airport, but it has a unique claim to fame: the world’s first airport duty-free store.

Today, the store has what you would expect — designer perfumes, jewelry and various fine foods, with a lot of local (in this case Irish) products in particular. But like the area around the airport, the shop started out small, with a local boy from the area who would go on to change the world of tax-free commerce in and beyond Shannon.

Before the Airport

Before the airport was built, there wasn’t much in Shannon. There wasn’t even a town called Shannon for anything to be in. Just some swampy marshland alongside the estuary of the river Shannon. But if the region wasn’t exactly a center of commerce and industry, the same could be said for much of Ireland.

Before the airport was built, there wasn’t much in Shannon. There wasn’t even a town called Shannon for anything to be in. Just some swampy marshland alongside the estuary of the river Shannon. But if the region wasn’t exactly a center of commerce and industry, the same could be said for much of Ireland.

When the country first gained independence, the Irish economy was still reeling from centuries of colonization, during which Ireland had one primary job: to produce cattle and crops for Britain. Any native Irish industry had been actively discouraged by to prevent competition. So well into the 20th century, while much of the rest of Europe was busy urbanizing and industrializing, Ireland was still a mostly agrarian country that exported little beside food.

Another factor had shaped the economic landscape of Ireland as well: the Great Irish Famine of the 1840s, which was set in motion by a potato blight. And British economic policies made it far worse, decimating communities like those found in the Shannon estuary. In a country of 8 million, this fame killed every 8th person, and triggered a massive wave of emigration.

A combination of colonization, rural poverty, the mass emigration all worked to depress the Irish economy. But in the 1930s, the rest of the world quickly discovered that Ireland had three crucial advantages: location, location, location! As it turned out, Western Ireland was a perfect place to land a plane, because early passenger aircrafts making transatlantic flights needed somewhere to stop and refuel.

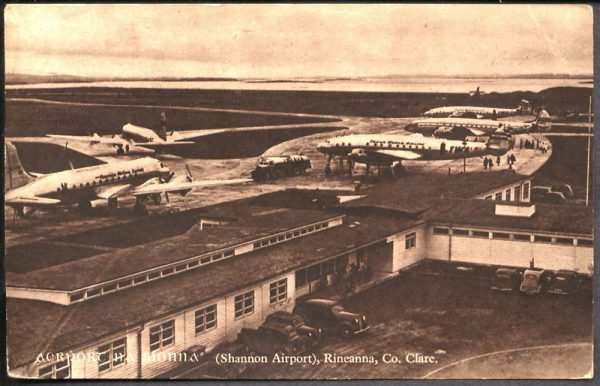

Taste of Ireland

In 1935, the governments of the US, the UK, Canada and the new Irish Free State agreed that all transatlantic commercial aircraft would be required to land at an Irish airport to refuel. And the location they picked for the airport was the estuary of the River Shannon. The airport at Shannon was an instant success. After all, they had a captive audience! In 1945, the now fully sovereign Republic of Ireland opened a concrete runway on the other side of the estuary, and within just two years the airport was handling up to 100,000 passengers a month.

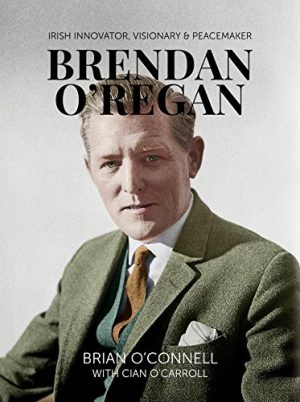

But there was still a lingering issue: the food at the airport continued to be managed by British Airways, and the fiercely independent Irish wanted to wrest control. A 26 year old hospitality worker named Brendan O’Regan, who was charismatic and had traveled abroad extensively, was tapped to do something new and better. From the beginning, O’Regan understood bringing high standards to Shannon’s food services wasn’t just gonna be about serving nice meals but also about giving travelers passing through a taste of Ireland itself.

From the moment O’Regan took over the restaurant at Shannon from the British, he started adding all these little touches. He improved the decor. He dressed the waitstaff in nice suits. Among other things, he inspired the chef to invent a new kind of alcoholic beverage for arriving passengers — the first ever Irish Coffee.

By the mid 1940s, everyone agreed the food at Shannon was better in almost every way than before. Now for most people, setting up a wildly successful restaurant at 26, burnishing your country’s international reputation and helping invent Irish coffee would be a fine enough legacy, but it turned out Brendan O’Regan was just getting started.

No Man’s Landing

In 1950, O’Regan was traveling back to Shannon from the US by ship. And on this ship there was this little shop, selling things duty-free because the ship was in international waters, and passing that savings onto passengers. And he thought: why not do this on land? O’Regan realized that all these transiting passengers in Shannon were essentially in a no-man’s land somewhat akin to international waters. They had left their starting port, but had not yet arrived at their final destination. So he reached out to government connections, and offered to run a government-owned store that would work the same way, for a cut of the profits.

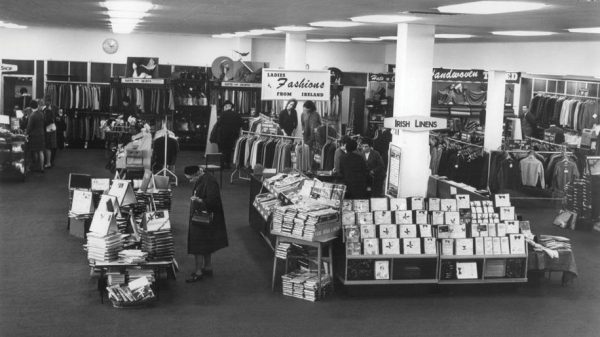

So in a move that has to go down as one of the most pivotal moments in airport retail history, O’Regan opened up the world’s first airport-based duty-free shop. Located in a small space at the entrance to the main lounge, passengers had no choice but to walk right through it. And because it was at an airport, this would be most passengers’ only chance to shop there. So rather than buying just a single bottle of Irish whiskey, it actually made more sense to just go ahead and buy an even dozen.

By the mid-1950s, the duty free shop at Shannon was a huge source of jobs, too, employing about a thousand people. And for six years, Shannon was the only airport duty free shop in the world. But the model spread quickly from there. Some people from Shannon traveled abroad to advise other countries on setting up duty-free shops. In other cases, international visitors would drop in to see how the operation worked for itself. Today, duty-free shops are everywhere, but it all started in Shannon.

The Free Zone

In the late 1950s, a leap in aviation technology threatened to undermine everything that O’Regan and his team at Shannon had built Jet passenger aircraft were faster, lighter, and could fly much further without having to stop for fuel, meaning airports like Shannon weren’t needed anymore. There were serious concerns that the Shannon airport was doomed to ever decreasing traffic, and thus: commerce.

In response, O’Regan and his colleagues would take the concept of duty free and apply it to way more than just a few stores at an airport. O’Regan had seen something similar to the duty free shop in Panama called a free port, a small area near the canal where ships could load and unload goods without paying customs. So, he thought, why not create something similar to a free port near Shannon? This time, the target wouldn’t be customers but rather industry more broadly.

In 1959, O’Regan made the pitch to his connections in the Irish government, and this time, got permission to put a fence around an area right beside the airport. Cross the fence, and you’d be subjected to normal import taxes, but stay inside, and you were in a ‘Free Zone.’ You could fly in components, assemble things, and ship out finished products all without paying taxes. Today, customs free zones can be controversial (which we will get into later!) but back then, O’Regan’s idea wasn’t controversial, so much as experimental.

In the ultimate “if you build it they will come” approach, with no committed clients, O’Regan’s team started to erect empty factory buildings in the zone, all set up and ready for occupancy, and used them to convince companies to set up shop. Once he had a few companies interested, many more followed. At first, it was mostly smaller American manufacturers that came. For them, Shannon was a convenient foothold into Europe. They were followed by big multinationals like GE, DeBeers, and a young Japanese firm called Sony.

After years of stagnation, Ireland’s larger economy was beginning to grow and industrialize, and Shannon had a not insignificant part to play in that transformation. It was also in the 1960s that Ireland’s centuries-long trend of emigration finally started to reverse. Many Irish emigrants (and their descendants) were now moving back to Ireland. And one of the places they were moving to was Shannon. But since there was no town near the airport to accommodate all of these incoming workers, they ended up building one — after years of population decline, it was one of the first new Irish towns in hundreds of years.

Now again, you would think: setting up a wildly successful restaurant, burnishing your country’s reputation, helping invent Irish Coffee, jumpstarting the national economy, attracting back emigrants, and founding your nation’s first new town in centuries would be a good place for Brendan O’Regan to stop … but he wasn’t done.

The Rise of Special Economic Zones

In many ways, Shannon’s industrial free zone anticipated the low tax, free market, global economy of the 1980s. But at the time, O’Regan viewed the entire Shannon experiment in explicitly anti-colonial terms. O’Regan became convinced that the best way for other developing countries to fight colonialism was capitalism. Starting in the mid 1960s, O’Regan began spreading the gospel of industrial free zones as the path toward economic independence.

In 1966, after consulting closely with O’Regan, the Taiwanese government opened their first free zone at Kaohsiung Harbour. And in 1972, with UN funding, Shannon began offering multi-week training courses where foreign officials could learn how to set up their own zones – now called special economic zones, or SEZs – based largely on the Shannon model. Visitors came from all over the world to learn more, including the future Chinese president Jiang Zemin.

In 1980, a Chinese delegation led by Jiang Zemin embarked on a 40 day world tour of various special economic zones. And at the end of that trip they came to Shannon. That same year, the Chinese government would set up not one, but four, special economic zones. Soon, this standard SEZ model became a major driver of the Chinese economy. By 1984, they’d already opened up fourteen more. Some of these zones might be only a few hundred acres, others are the size of small provinces. But, in one way or another, they’re all SEZs, which have become increasingly controversial over recent decades.

Today according to the UN, there are nearly 5,400 SEZs, in more than 100 countries. more than 1,000 of which were established in the last five years. The Shannon industrial zone is still around. But it’s no longer special. The fence is gone and since 2005, so too are the special tax breaks. They aren’t possible anymore inside the European Union. But Shannon has still had an outsized influence on Ireland itself. The country’s taxes are some of the lowest in the EU, with a comparatively deregulated economy focused on international investment – qualities credited with both the Celtic Tiger of 1990s and 2000s, but also Ireland’s record economic slump after the Great Recession. So for better or worse, while Shannon moved towards the Irish model, the rest of Ireland also moved towards Shannon.

The impact of special economic zones across the globe has also proven controversial. In many cases, when a new zone is being set up, the power dynamic can tilt towards the businesses and corporations that the zone is trying to attract. So if a government can help entice a company to its new zone by offering less labor protections or red tape, then some unfortunately are tempted to do just that. According to Patrick Neveling, who has researched SEZs extensively, this pattern has been seen in places like China and Mexico. And in some countries, labor laws are poor to begin with which leaves room for corporations to come in, set up shop in a low-wage, low-tax environment, and offer very little spill off benefits to the local economy.

The global proliferation of SEZs can also spark a “race to the bottom” when it comes to taxes, because, to attract businesses, countries around the world will offer lower and lower taxes in order to compete with each other. Low taxes means host countries aren’t getting the revenue from enterprises needed to finance their own development programs and social services, stifling the growth of their own class. Such concerns are a reason why many economists see SEZs and low-taxes as only an initial stepping stone for non-industrial countries to attract investment, not a long-term solution.

So the economic legacy of Shannon and SEZs more broadly can be tricky to untangle. But listening to oral histories, one gets the sense that O’Regan’s real goal for Ireland was something at once simpler and more complicated than economic growth: pride. “I have great regard for the English,” he said. “And I married one of them! But that situation … where we took over from them and did better than they were doing. It was a great spiritual uplift I can tell you for the Irish. And then we knew that we were as good as those empire builders.”

Comments (4)

Share

I’m from Ireland and I only learnt about Brendan O’Regan some years ago from the ‘This American Life’ podcast (at least, I think it was on TAL). From what I have heard, Brendan O’Regan made as great a contribution to the Irish economy as Seán Lemass or T.K. Whittaker. Hopefully, pupils in school today will learn about him.

The Irish, it seems to me, only like to celebrate their own once they have made it big abroad, as if the validation & verification from others is necessary.

Thank you very for an informative podcast.

In 2006, I flew Aer Lingus from Dublin to JFK. Imagine my surprise when moments out of Dublin, the plane landed in Shannon, which at the time, and perhaps still, was a port of entry into the US. There we were processed through US customs and immigration control, and given the opportunity to buy as much Bailey’s and whiskey as we could want “duty free.” Our flight then continued about a half hour later to the US as a purely domestic flight. Mr O’Reagan would have been proud.

This was a fantastic episode – I learned so much.

I wanted to chime in with an idea for a follow-up segment/episode that seems to tick all the 99pi boxes. The freeport idea explored in this episode has also had a major impact on the international art and antiquities markets. There are storehouses at freeports around the world, sometimes used for trade, but often ending up as de facto private museums for the ultra-wealthy to stash their art collections without having to pay taxes or submit to customs inspections, keeping them in these special facilities more or less indefinitely. There’s an underlying economic good that the system is meant to provide, but it’s arguably been exploited to facilitate tax avoidance and to give cover to trade in illicit art and antiquities. This article gives a good overview: http://itsartlaw.org/2020/11/03/behind-closed-doors-a-look-at-freeports/

Thanks again for an amazing episode!

Your airport map is missing Donegal Airport in Carrickfinn.

A minor discrepancy from an otherwise excellent piece!