Driving between Oakland and Los Angeles in February offers glimpses of a spectacular scene — neat, symmetrical rows of trees covered with pink and white flowers, stretching on for hundreds of miles. This is the annual California almond bloom. Almond trees take up a million acres of land in the state’s central Central Valley region. When the petals fall off, they carpet the road and create this sweet smell. To create a single almond, a blossom needs as many as a dozen bee visits, which means roughly 80,000 bees are required to pollinate an acre of almonds. “When you think of bees and business,” says reporter Adam Allington, host of The Business of Bees podcast, “you’re probably thinking of honey; but in fact, honey has little to do with commercial beekeeping today.”

Every winter, beekeepers from every corner of the United States descend on California to pollinate almonds. Almonds have a window of about two weeks for pollination to occur. Otherwise, the blossoms won’t turn into fruit. The demand is so high it takes upwards of two million hives, almost every commercial beehive in the country to do the job. “This is the largest managed pollination event on earth,” explains John Miller, a fourth-generation beekeeper from North Dakota who annually brings 13,000 hives over 1,500 miles to the Central Valley. For a beekeeper like John, pollination has become so lucrative it accounts for about two thirds of his income. He doesn’t sell honey. Instead, he finds it more cost-effective to leave it in the hive as food for the bees. After pollinating almonds, keepers like John will load their bees into a semi truck and move on to pollinate other crops in other states, like cherries, apples, watermelons and cotton.

Farmers have known for centuries that putting a hive of honeybees in an orchard results in more blossoms becoming cherries, almonds, apples and the like. Yet it’s only in the last 30 years that pollination services have become such an enormous part of American agriculture. Today, bees have become more livestock than wild creatures, little winged cows, that depend on humans for food and shelter. For thousands of years, our relationship with bees was much simpler. It really was all about the honey. Way before conventional sugar came along, honey was one of the few sweeteners humans had available.

8,000-year-old cave paintings in Spain depict people collecting wild honey and once humans got a taste for it, they’d do almost anything to get it. Apiculturist Alexander Zomchek studies bees and agriculture and explains that early harvesting was a “pretty raw event.” Collectors would smother and kill the bees with smoke and then take the honey, which wasn’t exactly a safe or sustainable strategy.

8,000-year-old cave paintings in Spain depict people collecting wild honey and once humans got a taste for it, they’d do almost anything to get it. Apiculturist Alexander Zomchek studies bees and agriculture and explains that early harvesting was a “pretty raw event.” Collectors would smother and kill the bees with smoke and then take the honey, which wasn’t exactly a safe or sustainable strategy.

By the Middle Ages, beekeepers in Europe had designed a method of capturing swarms of bees and putting them in woven upside-down baskets called “skeps.” When the first Europeans came to America, they brought along a few of skeps full of honeybees, which are actually not native to North America.

Apis Mellifera is just one of 20,000 bee species, but it is the only one that produces enough honey to be useful for humans. These docile, sweet-tempered bees did really well in the United States. One 17th century scholar had a saying that “the honeybees did better than the settlers did,” recalls Tammy Horn Potter, an apiarist who works with the Kentucky Department of Agriculture and authored Bees in America: How the Honey Bee Shaped a Nation. By the middle of the 19th century, honeybees were well established in North America. People were still keeping them in skeps or hunting small amounts of wild honey in nature, until a Presbyterian minister named Lorenzo Langstroth came along with a bold new idea.

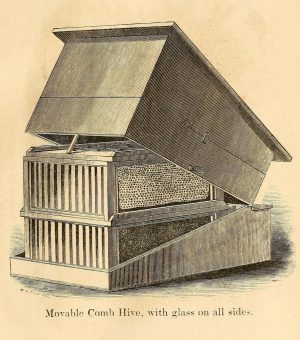

Suffering from a seasonal malady, Langstroth spent a lot of time wandering around outside near his hometown of Philadelphia. He developed a fascination with bees, and began to notice that there was a precision to the spacing between honeycombs. Each measurement yielded the same distance: three eighths of an inch. So Langstroth took this idea of the ideal “bee space” and he put it in a box. Inside each wooden hive, he would hang a series of removable frames spaced exactly the same distance apart. Bees saw an opportunity, took up residence and began turning these into colonies. It was the birth of the modern artificial beehive — efficient and portable. Langstroth’s innovations meant people could keep more bees, and the bees could reuse their honeycombs, because people weren’t destroying them all the time, all of which drove up honey production. Langstroth published a book on his findings in 1853 called The Hive and the Honeybee, which is still widely read in beekeeping circles today.

Suffering from a seasonal malady, Langstroth spent a lot of time wandering around outside near his hometown of Philadelphia. He developed a fascination with bees, and began to notice that there was a precision to the spacing between honeycombs. Each measurement yielded the same distance: three eighths of an inch. So Langstroth took this idea of the ideal “bee space” and he put it in a box. Inside each wooden hive, he would hang a series of removable frames spaced exactly the same distance apart. Bees saw an opportunity, took up residence and began turning these into colonies. It was the birth of the modern artificial beehive — efficient and portable. Langstroth’s innovations meant people could keep more bees, and the bees could reuse their honeycombs, because people weren’t destroying them all the time, all of which drove up honey production. Langstroth published a book on his findings in 1853 called The Hive and the Honeybee, which is still widely read in beekeeping circles today.

After World War I, people kept innovating and honey production moved from family farming to giant commercial operations. By the end of World War II there were around 6 million commercial beehives in the United States, which also set the stage for the next chapter of beekeeping: the rise of commercial pollination, which paralleled larger changes to American agriculture. In the 1950s, small family farms started getting pushed out by big companies and industrial agriculture. While family farms had fields with different crops growing side by side, the new model replaced that whole system with ever-expanding fields devoted to growing just one plant. Instead of planting cover crops to replenish the soil after the harvest, they would just use fertilizer.

Some commercial crops like corn, rice and wheat are pollinated by the wind, but many fruits and vegetables rely on insects to do the job. As the entire business became more and more industrialized, and shifted to monoculture, there was a need for greater certainty when it came to pollination. Commercial bees, thanks to the Langstroth hive, were a perfect fit. Controlled by humans and highly portable, they were able to do more pollinating in a day than most wild insects do in a week. So instead of trusting the local ecosystem to pollinate their crops, many farms came to depend on this single domesticated species of bee.

As farmers grew more crops, commercial beekeepers started earning more money by renting out their bees as pollinators. While pollination is big business in the United States, the country’s approach is unusual from a global perspective. Today, commercial beekeepers get most of their income from pollination. They’re paid around $200 per hive for a few weeks of pollinating almonds, which sounds like a lot, but the costs of keeping bees alive have grown, too. In the early 2000s, bees began to disappear en masse. Researchers were at a loss to explain “colony collapse disorder,” looking to causes like pesticides, disease and parasites. Colony collapse is when all the bees in a colony just disappear over the course of a few days. There are no bee corpses to autopsy and no obvious signs of poisoning. Around 2007, it was happening a lot. The number of cases technically labeled as colony collapse has actually gone down since then, but it’s still happening. Bees are disappearing or dying in huge numbers.

According to a recent survey of commercial beekeepers, the yearly die-off rate is about 40 percent, which is way higher than the 10-15 percent which used to be normal. Researchers point to the increased use of pesticides as one factor. When the bees started dying, many people blamed those companies but there was another problem: an invasive parasitic mite from Asia called varroa destructor. Varroa mites have wiped out tens of millions of beehives in the United States. Since the European honeybee didn’t evolve alongside the mite, the bees have no natural defenses. Also, because most of the commercial beehives in the country end up in a single place in California every February, humans have created the ideal scenario for these mites to spread from one hive to another.

There are farmers today who are trying to rely less on honeybee livestock by reintroducing wild bees and insects back into the pollination landscape. According to entomologists, just a small amount of plant diversity can help boost the population of wild bees and other pollinators like butterflies and beetles. One example of this is something called a “pollinator hedgerow,” which is basically a small strip of native weeds or flowers near the edge of a field that can provide habitat and food for wild insects and bees all year round.

The history of agriculture has a been a history of control, trying to bend nature to our will, and make it predictable and productive. For the sake of the bees, though, and maybe even the future of our food supply, we might need an agricultural system that’s just a little bit more wild.

* This episode originally reported that Alexander Zomchek is an apiculturist at the University of Miami in Ohio. The correct name of the university is Miami University.

Comments (11)

Share

Alex is a great guy and an amazing mentor. I was so happy to hear his voice.

Love, love, love the show so much but this episode really seemed to miss the mark. I’m glad the rusty patched bumblebee got the tiniest of shoutouts but generally disappointed with the centering of industrial beekeeping in the episode’s narrative. The travel intensive monoculture system exacerbates bee collapse [https://www.ehn.org/monoculture-farming-is-not-good-for-the-bees-study-2639154525.html] and it would have BEEn nice to hear from a different kind of beekeeper. Also there are sooooo many cool bee stories to tell that don’t involve the sustainability nightmare that is the almond industry, like the Meliponini stingless bees native to South America [https://ethnobiomed.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1746-4269-10-47], communities of urban beekeepers [http://www.bees.nyc], and hyper-local honey terroir [https://andrewshoney.com/product-category/new-york-city-honeys/]!

Appreciate all your good work – thanks for taking the time to read!

Thanks for sharing the article links.

In the intro ecology class I took in college some 30+ years ago, the principle demonstrated to us time and again in the science was the simple axiom, Diversity begets diversity, and homogeneity begets crisis. (Rather surprisingly, this was at a small evangelical school.) Even then, monoculture farming was recognized as an unsustainable path, and in the U.S. at least, government agricultural policy was simply broadening that road toward destruction.

Actually, Gabriel, thinking of bees as livestock and the industry of beekeeping was, in my opinion, one of the fascinating aspects of this episode. Always interesting to learn something new.

Amen. We need to get away from industrial beekeeping for many reasons, one of which the harm honey bees do to often more-efficient native bees species. Here’s a list of resources on that topic: https://www.monarchgard.com/thedeepmiddle/honey-bees-compete-with-native-bees

In the podcast, you said University of Miami, which is in Coral Gables, Florida. The correct institution is Miami University, which is in Ohio. As an Alumna of the former, I hate be confused with the latter.

I loved this episode! I am a lazy human who rents a house that happens to come with garden beds—my first house since childhood (I’m in my mid-30s). I wanted flowers, but I didn’t want a lot of weeding. So, my then-five-year-old and I learned lots about what native pollinators need, and we did our best to plant flowers that would bloom in three seasons. I got sick, completely neglected the garden, but we still have 5 foot tall amazing red flowers called Bee Balm! We also let our yard go pretty wild, but don’t tell the landlord… Our yard is greener than the neighbors with well-trimmed grass, though! I’m loving the beauty of wild and “weed” flowers and the winged creatures they feed.

Did y’all really just say ”native weeds”??

Thank you for fun and interesting reporting, as always. I was surprised there was no mention of the Independence almond variety, which is a newer self-fertilizing variety that does not depend on bees to pollinate. I’d heard about it years ago and wonder what effect, if any, it’s had on the pollinating bee business.

Hello,

Thank you For a very interesting chapter. There is a fascinating startup company called ״BeeHero” which collects smart data from inside the hive and produce a real-time analytics regarding the hive status and whether it will be efficient pollinating. You can check them out here https://www.beehero.io/

Sounds like a good sequel for this report!

Love the show!

The loss of honey bees has always been mostly hype and not much reality, so it’s disappointing to hear 99PI repeating that myth. Here’s my favorite podcast on the topic:

https://www.farmtotaber.com/episodes/2018/5/18/beepocalypse-now