“Informal urbanism” is a broad term. It applies to everything created outside the legal city planning and development processes. It can be a whole community, like a favela in Brazil. Or it can be a tiny thing, like a homemade road sign that helps drivers avoid a pothole.

But there are lots of actions that skirt the boundary between “formal” and “informal.” In the last decade, there’s been a rise in tactical urbanism and guerilla urbanism, where regular people make interventions in their communities. This ranges from hastily painted bike lanes, to do-it-yourself park benches in under-served communities. Gordon C.C. Douglas is the author of The Help-Yourself City and he spoke with Roman Mars about the concept of informal urbanism.

Hell Gate Bridge

Here’s a classic example of informal urbanism at work. Hell Gate Bridge in Queens, New York is a textbook case of a municipal failure that led to a DIY intervention. The bridge itself is an enormous feat of engineering, and it promises to keep standing long after humans have disappeared from New York. But like all infrastructure, over the decades, it’s become worn down. In 2010, the bridge started to leak and crack, dropping “scum” on the people walking underneath its archway. When it froze, the scum trail became dangerous and slippery, and when it was warm out, the trail was gross and slimy. So a handful of people living in the neighborhood close by built a small bridge out of reclaimed wood and shipping pallets so pedestrians could walk over this slimy substance. They called it the Astoria Scum River Bridge.

After the story got out about the scum river bridge, it caught some media attention, and a local councilman actually wrote a letter thanking the people behind the tiny bridge for their good citizenship. The source of the leak was eventually found and repaired, and the DIY bridge was taken out of commission. Douglas says this is the ideal of how informal urbanism is supposed to work — the community identifies a problem, makes an intervention, and the problem is solved.

Chaotic Cities

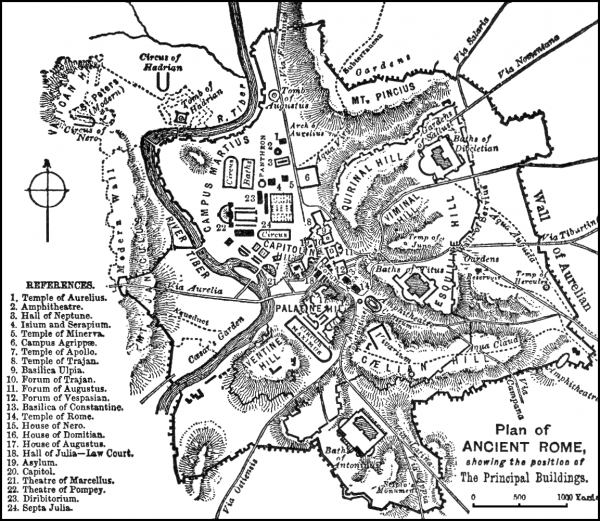

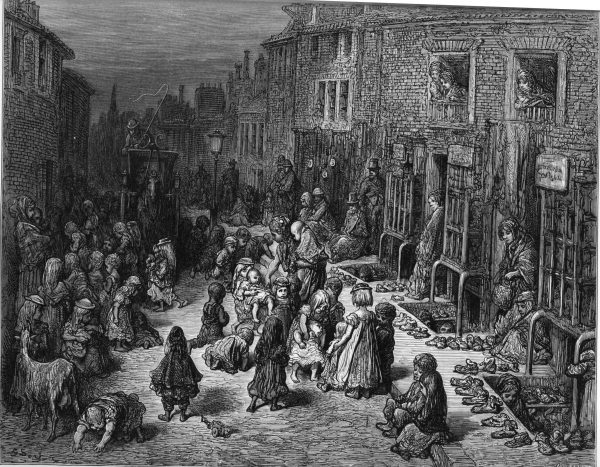

To understand “informal urbanism,” we have to talk about the origins of urban planning and “urbanism.” You can look at ancient Rome and find early signs of city planning. But the idea of a professional class of planners didn’t emerge until the 17th and 18th centuries, as cities grew more and more chaotic. Planners began to take charge of cities in the late 19th and early 20th century, as a reaction to the chaos of urban centers like London or Chicago, where unplanned neighborhoods actually put people in danger.

DIY Urbanism is a response to the failures of urban planning, and it gained in public awareness around the rise of street art in the 90s and early 2000s. As much as city planners might try, they can’t predict everything a community needs. They might not think about whether a curb is a little too high for a kid on a bike to climb.

Selfish Interventions

While the ideal informal intervention is community-minded and selfless, not all of them are made for such good reasons. Douglas gives the example of a man living in Seattle, who began to notice trash piling up at the bus stop outside his house after the city failed to put a trash can there.

Frustrated by the garbage, he decided to do something. But he didn’t want to install a DIY garbage can, because he worried this would make him responsible for storing the trash if the city didn’t get involved. So instead, he cut down the post with the bus stop sign, and threw it into the bushes. People thought the bus stop had been decommissioned. Eventually, bus drivers thought that too. The intervention solved the garbage problem. But it also robbed people in the man’s neighborhood of a convenient public transit stop.

There are much more extreme examples: people who paint red curbs gray to create parking spaces for themselves or wealthy Malibu homeowners who’ve been trying to stop the public from accessing beaches near their homes by putting up gates and signs declaring the space, falsely, as a “Private Beach.”

Many interventions are neither purely selfish nor purely benevolent. Take the case of the DIY bus benches in Los Angeles. These benches were installed to address the lack of public seating at transit stops. But planners dislike the DIY fixtures because they aren’t properly maintained. As a planner tells Douglas in the book, “Wait until someone gets a splinter, then it becomes our problem.” Oftentimes these DIY interventions will be more reflective of one person’s priorities than a more bureaucratic form of planning.

Here’s another bizarre dilemma that emerges from DIY planning — when informal urbanists are working against each other. Bedford Avenue is one of the longest streets in New York City, and for years, it had one of the longest bike lanes in Brooklyn. But the lane passed through a predominantly Hasidic community in South Williamsburg. The Satmar Hasidim didn’t like all of the scantily-dressed hipsters biking through their neighborhood, and they were able to get the city to remove the bike lane.

The removal of the bike lane was seen as a real affront to the cycling community, so a group of “do it yourselfers” went out in the night to try to re-stripe the bike lane. They were apprehended by the Shomrim, the informal police force that works for the Hasidic community, who held these do it yourself bike lane painters until the NYPD arrived. Douglas describes it as a situation where a kind of DIY police force took action against DIY activists — exposing the rifts in the community and showing the limits of informal urbanism.

Time Square Is For Walking

The aesthetics of informal urbanism has begun to show up in formal planning as well. There are positive urban trends toward walkability, livability, pedestrian public spaces, complete streets, and tactical urbanism. For example, the New York City’s Department of Transportation employed the ideals of tactical urbanism to change Times Square from a big, complicated road intersection to a pedestrian plaza, with places to sit and little access for cars.

We see the same thing in San Francisco with the Pavement to Parks program and the huge proliferation of parklets throughout the city. And in the spirit of tactical urbanism, many of these small parks are set up cheaply, quickly, and with an aesthetic that looks personal and handmade.

Comments (7)

Share

I found this episode particularly interesting since I live in Rome, a city in shambles, where associations of citizens have risen everywhere often as the only solution to avoid total disaster for parks and playgrounds, and other public areas. We have a group called Retake that organizes flash cleanings of schools and streets. I wish Romans had more sense of civic duty though, because were in the middle of a crisis, and most people still act as slobs…

On a different front, there are people doing tech for civic good too. I’ve been a part of Civic Camp NC since the first year here in the Raleigh-Durham NC area.

http://ncopenpass.com/civic-camp/

Different years bring different things, but it’s a great chance to do something.

Great episode – reminded me of Jim Bachor – an artist that fills potholes with mosaics. https://www.bachor.com/pothole-installations-c1g1y

In the battle of the “Hasidic vs Hipsters” did the Hipsters ever consider just cutting the eruv? I think that would have been a better and possibly more effective strategy.

The Eruv is sanctioned by the city, it’s not simply something put there without permission. Same with the Shomrim volunteer police force, I assume they regularly work hand in hand with official authorities, which is why they were able to hold the perpetrators until police arrived without fear that they themselves would be in trouble. Cutting the eruv and painting DIY bike lanes would be vandalism!

Very entertaining show. It is interesting that well intentioned activism can fall foul of the authorities, such as this German court ruling yesterday.

What court case are you referring to?