In 1959, after nearly a century and a half of British colonial rule, the people of Singapore took the first step toward their independence. They voted to run their own internal government. It was a joyous moment. But they inherited a difficult situation.

The island had been bombed heavily by Japan during the Second World War, and again by the Allies after Singapore fell to the Japanese. A lot of their infrastructure was in ruins, including the port, which had brought foreign goods and a multiethnic, multilingual population of people to the island for centuries. And no port meant no jobs. At their first moment of independence, poverty was rampant. Most of the island’s residents were living in unpermitted, makeshift houses, crammed into crowded villages throughout the island.

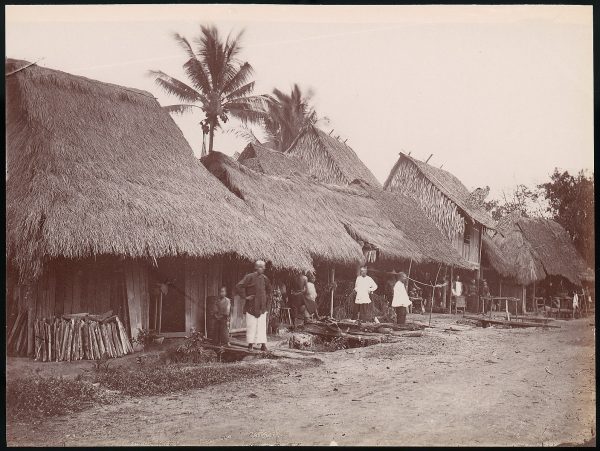

Singapore is tiny, and today the entire nation is really just one city. It takes less than 45 minutes to drive across the island, with traffic. But in the 1950s there were mainly villages known as kampongs, a local Malay word. Kampong communities were strong and close-knit, but the living conditions weren’t easy. Multiple families might share one toilet or one kitchen. Many of the kampongs relied on gas for lighting and cooking. And most houses were made of super flammable palm leaves or wood with roofs made of sheet metal.

The government wanted to raise the quality of life for the people. They rebuilt the port and created factory jobs, and made all kids learn English so that Singapore could feel united under one language. But the biggest undertaking of all was to get their people out of thatched-roof huts and into modern housing, and one of the biggest challenges would be doing it with extremely limited land space.

Going Vertical

In 1960, they formed the Housing and Development Board or HDB, and just five years later they had already housed 400,000 people! Only Russia and West Germany had had rehousing rates as fast as Singapore, and the HDB achieved this pretty amazing feat by going vertical.

When planning for a growing population, most urban planners expand their cities outward, but in land-limited Singapore, that’s not an option. Today, Singapore’s tallest public housing buildings are 50 stories high –the tallest in the world. Today, Singapore is the third richest nation in the world, and 80% of Singaporeans still live in these tall, cement HDB flats and there are about 10,000 public housing buildings on the island. It’s not the glitzy, futuristic Singapore skyline you see in movies like Crazy Rich Asians. Much of the island is full of tall cement buildings with housing block numbers, painted boldly down the sides, which help Singaporeans locate themselves in the monotonous sea of nearly identical buildings. And new flats are going up all the time.

Throughout the 1960s and 70s, HDB public housing developments sprung up all around the country. Khoo Ee Hoon is a historian in Singapore. She was born in 1966 and has lived in HDB flats for most of her life. She remembers watching this housing crop up everywhere on the island. “Design style is different. But what doesn’t change is basically everything become[s] like a matchbox, you’re living in a little hole inside a concrete structure.”

As people moved into these drab concrete towers, a lot of them missed the vibe of their old communities — what they called the “kampong spirit.” But there was a lot to like about their new homes — such as having their own bathrooms and kitchens with electricity and plumbing. So people moved in, and the government kept building.

Peck San Theng

In Singapore, where land is scarce, it’s not unlikely for apartment buildings to be built on top of land that was graveyards not too long ago. But building on top of a graveyard has its complications, and in one cemetery called Peck San Theng, the new housing development disrupted more than just the dead — it disrupted a way of life. “When I was a kid […] wandering around the hillsides, you know walking through the grass, we [said] prayers. We [made] offerings,” says Kwan, someone who grew up near Peck San Theng cemetery. His father would bring him to the cemetery to pray at the graves of their family and friends. Kwan’s family was Chinese, and they believed that if the dead were well-taken care of, it not only meant peace for the departed, but it could also bring direct benefits to the descendants.

Going to the cemetery wasn’t just a family affair, it was a community function. Chinese migrants to Singapore set up social service organizations to help take care of their community from the cradle to the grave, and beyond. Mr. Kwan and his friends would wander the untamed hillsides to the graves of their long-dead community members. There, they’d burn incense and fake paper money–things they thought the dead might need in the afterlife. And then, they’d hang out at the grave.

Peck San Theng cemetery was sprawling with huge, ornate tombs that could be up to thirty meters wide. A single-family tomb like that could easily be bigger than a three-bedroom HDB apartment today. On top of that, Peck San Theng had a lot of shared graves. One big tombstone would mark a huge area where members of a professional or social group were buried together. At Peck San Theng, there were plots for all sorts of groups, like the tailors’ association, the pork sellers’ association, the opera singers’ association.

But Peck San Theng was not just a place for the dead. It was in fact, a cemetery full of life. It was a self-sufficient village that began almost a hundred years before Mr. Kwan started visiting. When members of Singapore’s growing Cantonese community realized they needed more space to bury their dead, they purchased land on what was then the edge of town. And as the cemetery grew, so did the village. An active graveyard meant there were jobs to be had. Graves had to be dug, tombstones carved, refreshments sold to mourners, so people built thatched roof homes right there among the graves. This actually happened in a lot of big cemeteries that sprawled across the tiny island. The living just lived alongside the dead.

Making Room for the Living

By the 1970s, Peck San Theng village had almost 2,000 residents. There was a large, Chinese-style gate at the entrance to the village. The village had its own clinic, convenience stores with thatched and tin roofs. Many of the residents worked at a soy sauce factory in the village. Livestock was reared, kids were born, and families raised, all among the graves. But life in the cemetery was about to change. As the HDB built more and more housing for Singapore’s growing population, they realized they needed more land. The dead would have to make way for the living. In 1973, the government said there’d be no more ground burial at over 70 cemeteries, including Peck San Theng. By 1974, those who died could only be buried at the single, more sterile government-run cemetery 16 miles from the city center. Or, for a fraction of the price, they could be cremated, their ashes scattered or stored in a small urn.

These were huge cultural changes. Not everyone was happy, but after the war and the nation’s independence, a lot of Singaporeans were willing to make sacrifices for the country’s development. A lot of people acknowledged that burying people in big graves just wasn’t sustainable on a tiny island. Also, they had to go along with the changes — Singapore has really limited freedom of speech, so when the government tells you to do something, you don’t have much choice.

In 1978 Peck San Theng cemetery association received a letter from the Housing and Development Board saying a new, high rise public housing development was going to be built on the cemetery. Their land was being reclaimed. Both the living and the dead were given four years to clear out. The people living in Peck San Theng were mostly relocated into new government housing nearby, but it took a while. A lot of the villagers weren’t happy to leave, and they stayed as long as they possibly could. Sometimes years past the deadline the government gave them to move.

Mass Exhumation

As the deadline approached, only about half of Peck San Theng’s 100,000 graves had been unearthed. The association members were at a loss as to what to do with the nearly 50,000 bodies still in the ground. Who would pay to dig up the graves, cremate the bodies, and give them another resting place? The association explained their predicament to the Housing and Development Board, who agreed to help them deal with the lingering dead.

After years of digging, the 100,000 bodies were all removed. The half that were unclaimed were cremated together and scattered at sea in a solemn ceremony. Many other living members of Peck San Theng were rehoused in a nearby HDB estate. For most of the villagers, the transition wasn’t easy. Even though their housing was taken care of, their livelihoods centered around the cemetery, which all disappeared.

Members of the Peck San Theng association wanted to retain part of their land, and after a long legal back-and-forth, the government awarded them eight acres of their original 324. It was enough to build a few administrative buildings, and a columbarium–a building made to hold urns. There, they’d put the cremated remains of many of those who had been buried at the cemetery. But when it came to building the columbarium to house the urns, there was no real local “tradition” to harken back to. Columbariums were novel structures because the whole practice of cremation was pretty new to a lot of Chinese Singaporeans. Just 20 years earlier, only ten percent of the country’s Chinese population was cremated. But by the time Peck San Theng wanted to build their columbarium, that number was almost 70 percent.

Condominium for the Deceased

Without much by way of architectural precedent for the columbarium, the Peck San Theng association took a gamble on a somewhat controversial architect — a modernist named Tay Kheng Soon, who cut his teeth designing brutalist superstructures. From the outside, it almost looked like another new multi-story construction for the living. Before the columbarium opened in 1986, one newspaper said it could easily be mistaken for a flashy new condominium. The inside, however, was different. Mr. Tay’s columbarium stretches up over about nine different staggered levels. The building rises gently in a series of cascading stories and half-stories, forming cement hills, like traditional Chinese tombs. The large windows and skylit corridors made it sunny and airy. Urns line the walls, from floor to ceiling. There was a waiting list of over 20,000 urns from the cemetery ready to move into Peck San Theng columbarium. But nearby housing units for the living weren’t so quick to get sold.

As promised, those HDB flats were going up all over the grounds that were filled with dead bodies just a couple years earlier. They called the development “Bishan,” a Mandarin version of the Cantonese “Peck San,” or “Jade Hills.” The new Bishan development had everything the HDB imagined people needed. Many other Singaporeans live on old cemeteries, whether they know it or not. So many other cemeteries were cleared for development, and it’s still going on right now.

Losing the cemeteries has forced a total 180-degree turn in how a lot of Singaporeans think about dying. When the first government crematorium opened in the early 60s, they did about four cremations a week. Now, more than 80% of Singaporeans get cremated when they die — substantially more than in the US, where that number is just over 50%. And all of those traditions that people like Kwan did, like burning offerings and having a feast at the grave, have had to be drastically downsized to fit in the tight hallways of the columbariums.

Today, Singapore has four government-run columbariums, but this solution doesn’t meet everyone’s needs because they only house cremated remains. Chinese are the ethnic majority and the country’s Hindu community has long practiced cremation. Most of the country’s large Malay community practices Islam, which doesn’t permit cremation.

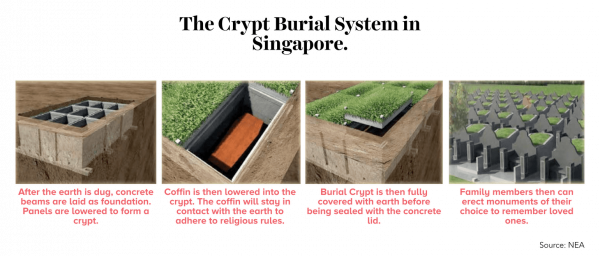

In 2007, the Singapore government implemented its new “Crypt Burial System.” It’s a prefabricated series of interlocking concrete walls, assembled above ground and then sunk into the earth. The catch is that you only get fifteen years in your own grave, and then you have to be consolidated with others which can be up to 16 bodies per grave.

All of this rearranging of the dead has been a painful change for a lot of Singaporeans, but there was also a widespread understanding that something had to give in order to get so many people their own homes on such a tiny island. Singaporean people had to sacrifice — the entire population has had to reconceive of their rituals around death. The country gave up acres upon acres of land for the dead all to get homes for the living.

You can learn more about Katie Thornton’s project Death in the Digital Age and follow the project here.

Comments (8)

Share

Ummm, I totally suggested this episode a few months ago. I’m really glad you did it, but it would have been great to get a shout out for our podcast – Home on the Dot – which had an episode on HDB flats in Season 1 and has an episode on columbaria — we title ours “High-rise Dying” — coming in Season 2.

I really want to highlight this podcast because it is co-produced with my students, who have done amazing work on all aspects of the project. A shout out would be amazing for them.

Hi Chris – an outside journalist (working on a project about death and cities) pitched us on this story a while back, so I’m not sure if the 99pi staff person who got your suggestion on our end was aware we had a story about this in motion already. Regardless, your podcast is definitely up our alley – I’ll share a link around the office and put one in this comment for other 99pi listeners! https://blog.nus.edu.sg/homeonthedot/

You guys rock. This is not a roast but a simple curb to keep your show the best on the airwaves.

Please do a show on “cement” vs “concrete”or at least use it properly. Perhaps you could pitch it to Helen at “The Allusionist.” Simple confusion but not to be confused. You guys should know better… :)

Hello! I am a long time listener of the show. I was listening to this show as I was boarding the MRT from Bishan! I have been staying in Bishan my whole life, my dad serves in the planning committee of Peck San Theng association. Superb show, so happy to hear a shout out to Bishan! Best, Phoon.

“Cement buildings” really? My ears are bleeding.

Hi I am a regular listener of this podcast in Singapore, and this episode is really close to my heart. I have a vague memory of visiting my grandfather’s grave in the old Peck San Theng, and my grandmother’s grave is now in the new Peck San Theng. Thank you for recording this gem of cultural history!

I listened to this episode on the plane to Singapore! Great timing. Thank you for helping me appreciate Singapore in a different way.

Hi! This might sound strange but did you happen to ask more about the reported “shadows” around one of the remaining pavilions? Hearing this brought back a day from some 5 years ago in Helsinki. My girl friend at the time came home excited saying that I have to see this and led me to street that’s crossing through two cemeteries. On one side there was a dark shadow floating in the air. The best way to describe it would be if you’d imagine a bit of smoke in the dark and shining a beam of light through it from below. The shadow was that kind of a shape some 15 meters above the ground except a dark one. We could walk on the street an observe the shadow from different angles. There were a couple of other people also on the street pointing at it. To this day I’ve wondered what kind of a natural phenomenon could cause a dark shadowy shape to float above the ground in that way.