In the heart of the Caribbean, there is a little island called Anguilla. At its widest point, it’s only about 16 miles across. Anguilla’s white sandy beaches and crystal blue waters have made it one of the most desirable tourist destinations in the Caribbean, but back in the 1960’s Anguilla didn’t have any of the beachside villas, luxury spas, or golf courses that it has today. “It had dirt roads, no electricity, one stoplight in the middle of town,” explains Emily Oberman.

Emily used to visit the island on family vacations as a kid because her parents, Marvin and Arline Oberman, were successful graphic designers from New York City and they liked to travel off the beaten path. After her father passed away in 2018, it was actually a graphic that he helped create that got Emily thinking about Anguilla again… A graphic on a small flag.

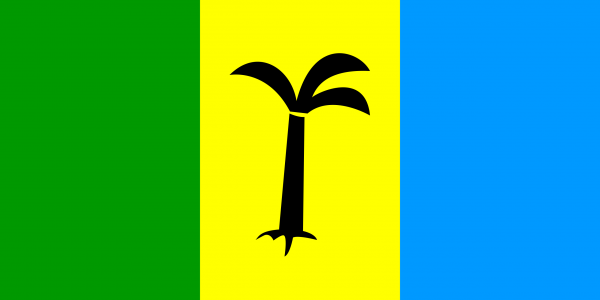

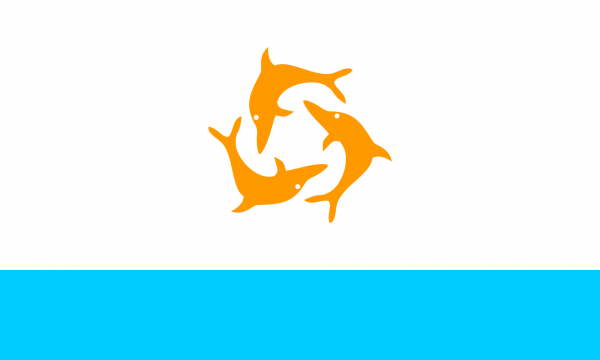

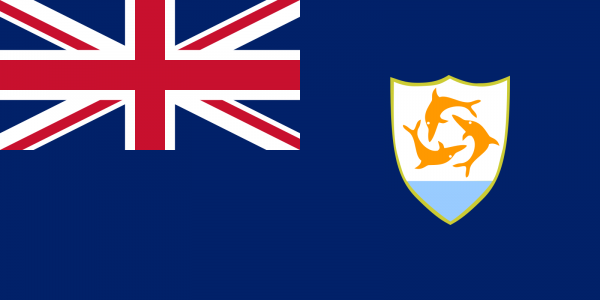

The flag was all white with a thin strip of brilliant turquoise blue at the bottom, with three orange dolphins arranged in a continuous circle in the center. Emily knew that her father had gotten involved with the design on one of their trips to Anguilla and that it had actually flown there for a couple of years. So four decades later, inspired by this keepsake, she decided to take a trip back to Anguilla to honor her father, and show her own family this place that had been so important to her childhood.

As her family approached the island by ferry, she noticed a large sign welcoming travelers to Anguilla, and she couldn’t help but notice the colors—turquoise, white, and blue just like the colors on the flag her father created. But they weren’t just on the welcome sign, they were on almost everything. The colors were in the customs office, on the pylons on the road, the colors of the gas station—everywhere!

It turns out that her father’s dolphin flag was a bigger deal than Emily had realized. And that her parents, a couple of graphic designers from NYC, had played a very small but not insignificant role in a key moment in the island’s history. This flag that had been collecting dust in the family attic was a symbol of one of history’s strangest political revolutions.

The Forgotten Colony

Anguilla had been one of Great Britain’s many overseas colonies since the 1650s, but unlike many of Britain’s other Caribbean territories, Anguilla was missing a lot of essential services like electricity, paved roads, and proper schools all the way through the 1960s. Timothy Hodge is the former president of the Anguilla Archeological and Historical Society, and he explains that the island has basically been neglected by Great Britain. “if you read the historical records, it was not recognized as having any value to the British crown… so nobody paid any attention to it,” says Hodge.

Anguilla’s soil wasn’t fertile enough for large-scale agriculture, and according to Hodge, if the British couldn’t establish the same large slave plantations on Anguilla that were common in the rest of the Caribbean, then they didn’t have much use for it. So for decades, centuries even, the British basically ignored the island which meant Anguilla got very little funding for development.

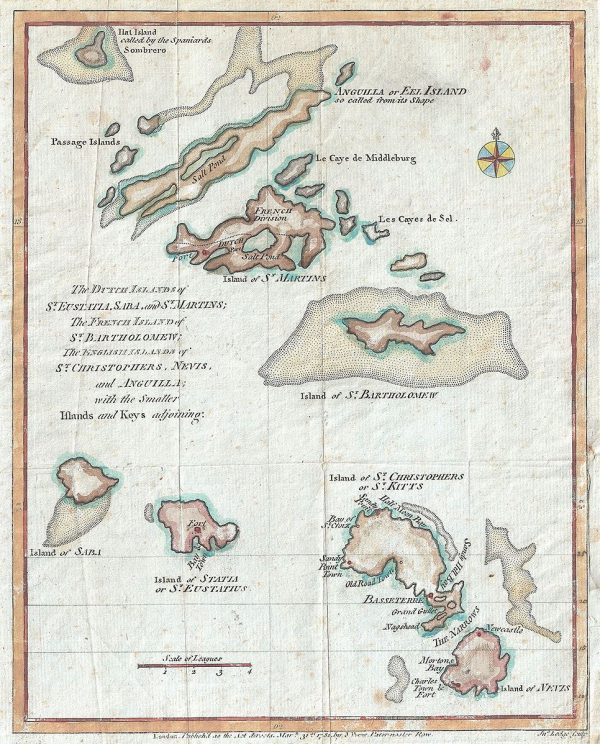

In 1825, Britain decided to lump some of the smaller islands together to form a single colony. Anguilla would be treated as one part of a multi-island colony along with St. Kitts (also known as St. Christopher), and then eventually with Nevis—with St. Kitts in administrative control of the union. Suddenly Anguilla went from essentially independent self-governance to having to answer to St. Kitts for everything. But there was one huge problem with lumping Anguilla with St. Kitts… Anguillians did not like the Kittitians. “It just was a match that was never made in heaven,” says Hodge. St. Kitts and Anguilla were two very different islands, with very different relationships with Great Britain. Anguilla was so much smaller than St. Kitts and Anguillians felt that all of the aid money that came from Britain always ended up in St. Kitts, and Anguilla was still lacking a lot of the essential infrastructure like electricity and running water.

Don Walicek studies Caribbean history at the University of Puerto Rico, and he says that there was one story circulating that Britain had allocated funds for a pier to be built on Anguilla, and instead St. Kitts built the pier on St. Kitts and simply named it the “Anguilla Pier.” Tensions between the two islands simmered for over a century, until 1967, when Britain made a decision that would turn their feud into open conflict. Rather than separating the two islands as Anguillians wanted, the British government decided that St. Kitts, Nevis, and Anguilla wouldn’t be a single colony anymore, but an official self-governing “associated state” with St. Kitts in control. This situation seemed much worse to Anguillians because they would be at the full mercy of St. Kitts. “At least with colony status, they could complain to Britain. But after that, they would have nobody to complain to,” explains Hodge.

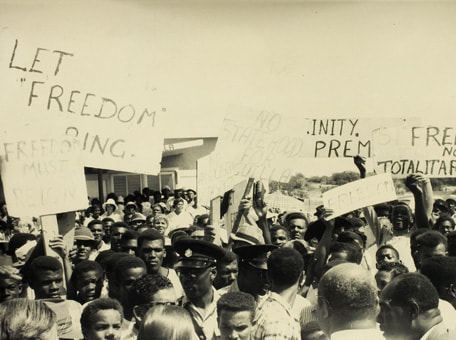

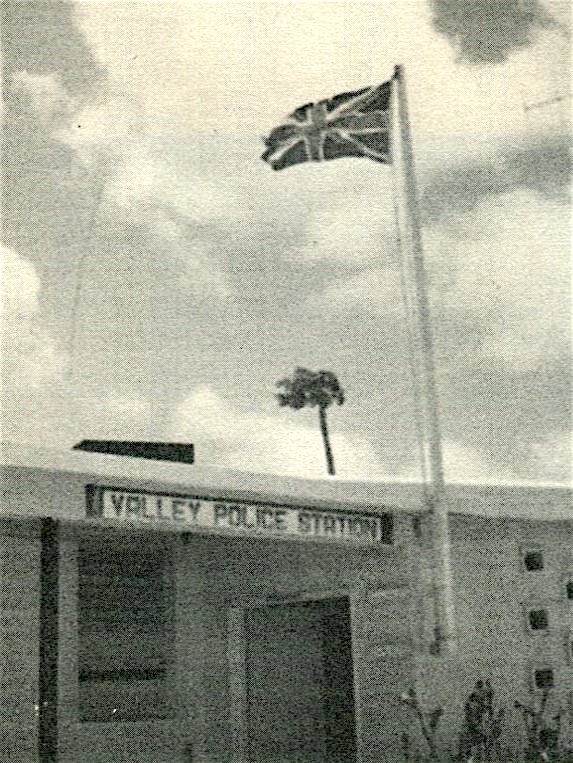

Anguillians began protesting immediately. The police force on Anguilla was made up of 17 Kittitians, and they became a symbol of Kittitian authority. And so in February of 1967 Anguillian rebels rounded up all 17 officers and booted them off the island. This was the first act in the Anguillian revolution.

The Anguilla Revolution of 1967 caused a lot of historians to scratch their heads because this was not actually a movement towards independence… Anguilla was calling for independence from St. Kitts, and dependence on Great Britain. The island wanted to go back to being ruled directly by the British because they figured it was better to be loosely ruled by a country half a world away than tightly policed by your next-door neighbor.

A Good Flag

As all this was going on, a young Emily Oberman and her family were on one of their trips to Anguilla. Emily’s father Marvin first learned about the conflict over breakfast when he overheard two men recounting a “raid” on the police station. “They said that there was an attack on the police station and one of the guys apparently was very proud that he had shot two bullets,” says Emily Oberman, “But the police station was closed at the time, so he was just shooting two bullets at an empty building.” Curious, Marvin Oberman started asking around and was eventually introduced to a man named Jeremiah Gumbs who was able to explain the revolution… because he was involved.

Gumbs had moved away to the US in his twenties but had come back to Anguilla with his wife, Lydia, to open up a hotel. He didn’t have an official role in the government, but he became deeply involved in the politics of the island. They even gave him the nickname the “roving ambassador.” “He was very involved in where the revolution was going and how it was gonna be handled,” explains Emily. Jeremiah and Lydia knew that if this revolution was going to capture people’s imagination, they needed a good flag. It isn’t entirely clear whether the Gumbs’ reached out to Marvin, or if Marvin reached out to them, but one way or another, Emily’s father helped create a whole new flag for a whole new political future.

“The idea behind the flag was that he wanted it to be incredibly simple,” says Emily. Lydia Gumbs and Marvin settled on three colors: white, blue, and orange. White for peace and tranquility, the blue base representing the surrounding sea and also faith and hope, and the three orange dolphins at the center symbolized endurance, strength, and unity in a perpetual circle. Marvin coordinated with Lydia from his office in New York and mocked up a prototype. Alan Gumbs, Jeremiah and Lydia Gumbs’s son, claims that it was actually his mother who designed the famous dolphin flag, while Emily Oberman believes her father Marvin is the designer. Perhaps Marvin and Lydia held different definitions of the word “designer,” but both clearly worked very closely together. As a successful graphic designer herself, Emily has a healthy perspective on the debate saying, “To me, a project that is successful is one where everyone who worked on the project thinks that they were 100% responsible for it.”

The Mouse that Roared

Anguillians had a flag and revolutionary spirit, but they were still stuck in a confusing tangle of colonial bureaucracy because they were fighting for independence from St. Kitts… but not Great Britain. Revolutionary leaders tried to negotiate a direct relationship with Britain, but Britain refused to deal with Anguilla without going through St. Kitts first. Anguilla did not want to do that, and so the tension just continued to escalate. But even with this tension, it remained a bloodless conflict. “The man who eventually became known as the father of the nation in Anguilla, Ronald Webster, said the revolution was really a war of words,” says Walicek, “He meant that he won a lot of battles with words, with threats, with conversations with reporters.”

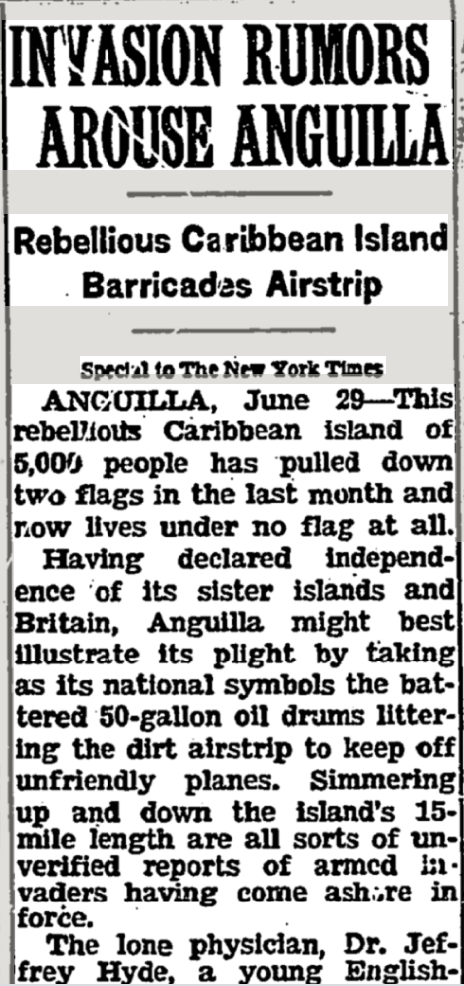

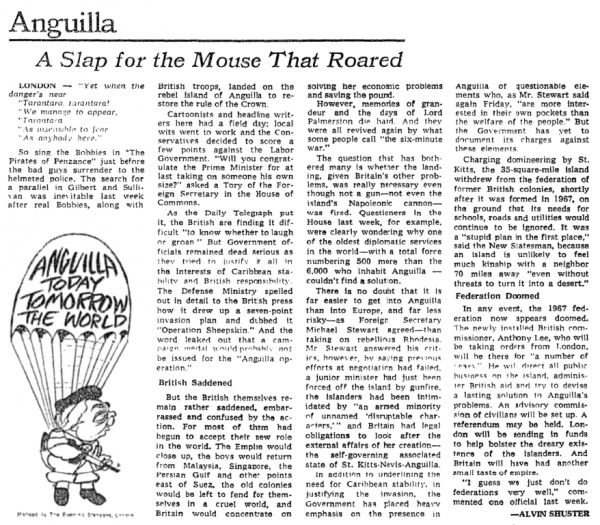

The media was captivated by the story of this tiny island in a territorial dispute with one of the most powerful nations in the world, and their struggle was in the New York Times every day for months. The media had dubbed Anguilla “The Mouse That Roared” after a satirical novel by Leonard Wibberley about a tiny nation that declares war on the US. Reporters couldn’t help but see an ironic similarity between the two situations because Anguilla was this surprisingly ferocious island that refused to back down.

More than anything, the revolution marked a huge shift in what it really meant to be an Anguillian and united Anguillians behind a single purpose under a single flag. But despite this new unity, St. Kitts still had the power, and they were withholding everything from postcards to pensions, and they lost their patience. In February of 1969, two years after Anguilla declared independence from the Associated State, it took a more drastic step and declared independence again—but this time it was from the British. As a tiny nation with no diplomatic recognition, this was an incredibly risky move, but Anguillians voted 1,739 to 4 to end all ties with Great Britain. The Union Jack that had flown alongside the dolphin flag since the start of the revolution was taken down because they decided they would rather try to make it entirely on their own than have any connection with St. Kitts.

The Bay of Piglets

Britain wasn’t ready to let go of the idea Associated State, and they attempted a last-ditch effort to save the union. They sent a British representative to Anguilla named William Whitlock to try to negotiate with Anguillians. According to Walicek, the Anguillians welcomed Whitlock at the airport with a stirring rendition of “God Save the Queen.” As a sign of respect to Whitlock, Ronald Webster, the Anguillian leader came dressed to impress in a dinner coat and gloves. The courtesy wasn’t returned and apparently, Whitlock blew off an invitation to have lunch with Webster and instead ate with another British official stationed on the island. Feeling disrespected, the Anguillians asked Whitlock to leave the island. When Whitlock refused, Anguillians fired some warning shots into the air, and Whitlock fled the island in fear. Humiliated, Whitlock exaggerated accounts of violent Anguillians prepared to kill him, which spurred Britain into action.

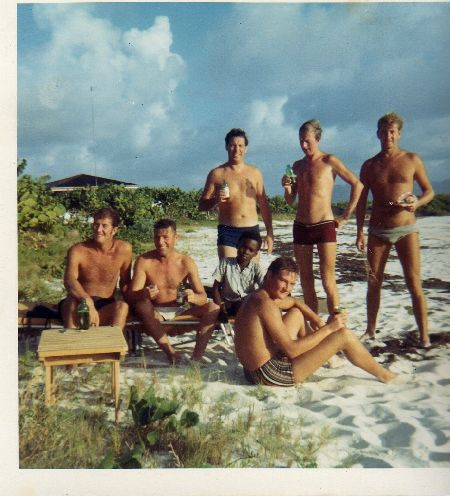

Britain decided the only way to respond was by mounting a full-scale invasion to restore order. Two Royal Navy frigates landed on the island along with 350 paratroopers. British forces parachuted onto the island and stormed the beaches, probably expecting armed resistance, but all they found were reporters snapping photos and some very confused Anguillians. Because the declaration of independence from Britain had been so recent, a lot of islanders thought that maybe the British were there to make Anguilla a direct colony again like they had originally wanted, with some even bringing food out to the troops in solidarity.

The Anguillians didn’t put up any resistance. There was very little violence and certainly no casualties. Once word got out about the so-called Invasion of Anguilla, the British became a punchline calling the operation “The Bay of Piglets.” The Anguillians allowed British troops to search their homes for weapons and watched as they replaced the dolphin flag that flew over the administrative office with the Union Jack. Anguilla had been taken without a fight. But in a way, Anguilla won the war. “Anguilla won the war because it had essentially achieved what it wanted to achieve in the first instance,” says Hodge, because the island was technically under colonial rule again. And, more importantly, they were no longer under the thumb of St. Kitts, which was exactly what they had been originally fighting for.

A Different Sort of Independence

Since the British had gotten themselves into a public relations nightmare, they had a lot of damage control to take care of. They started development programs to pave roads all over the island and a new runway for the airport. They also trained a new police force made up of locals. They didn’t just have to make up for a disastrous military move, but for centuries of colonial neglect. “Anguilla received more support than it had ever received in all of the hundreds of years of British colonization,” says Walicek, “So in a matter of a couple of years, it began to have infrastructure, schools, a mobile library built, health professionals were stationed there.”

Anguilla was given the support that it needed to develop its economy and create a thriving tourism industry. It took over a decade to negotiate the terms, but by 1980 Anguilla had achieved full separation from St. Kitts and was officially a direct territory of Great Britain. It isn’t technically correct to say that Anguillians achieved independence, but today the country has its own constitution and government. “There’s this parallel, very powerful and convincing narrative, and maybe a small place with such a different history… maybe they should be allowed to have sort of their own understanding of what independence is,” says Walicek.

Even though you can still see its presence all over the island today, the dolphin flag of the Republic of Anguilla was only officially flown for about two years. Once Britain invaded it reverted back to the Union Jack and then got a completely new flag in 1990. The current design is a blue field with the Union Jack in the upper left canton, with a clashing orange dolphin coat of arms on the right-hand side. Most British overseas territories adhere to that particular style guide and to be honest… it’s a little cluttered compared to the dolphin flag created by Marvin Oberman and Lydia Gumbs. But in a way, the design of the current flag is an appropriate, if complicated symbol of what the country is and what it wanted to be.

Comments (4)

Share

Stories come and stories go, but there’s always time to talk about flags.

Anguilla in italian means “eel”, and that´s what the island was apparently named after, for its long shape (according to the internet, by Columbus himself). A flag with eels going in a circle would also have made sense I guess.

Sounded interesting, but couldn’t listen to it because of the background “bzzzzz” that was playing behind the main track. Please never do that again – it was awful!

This comment is not about Anguilla but the discussion at the end about the new book and in particular traffic lights:

Check out the lights in Foz do Iguacu, Brazil which are a far superior design to the standard red/amber/green as they give a “time left” indicator. We only saw them in Foz do Iguacu though that was 2015 so maybe that has changed. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GpnAvwHk41A