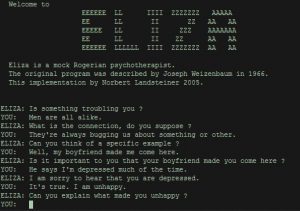

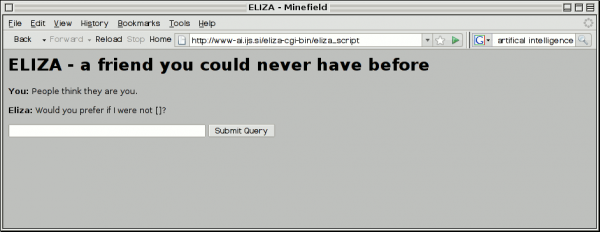

Throughout Joseph Weizenbaum’s life, he liked to tell this story about a computer program he’d created back in the 1960s as a professor at MIT. It was a simple chatbot named ELIZA that could interact with users in a typed conversation. As he enlisted people to try it out, Weizenbaum saw similar reactions again and again — people were entranced by the program. They would reveal very intimate details about their lives. It was as if they’d just been waiting for someone (or something) to ask.

ELIZA was a simple computer program. It would look for the keyword in a user’s statement and then reflect it back in the form of a simple phrase or question. When that failed, it would fall back on a set of generic prompts like “please go on” or “tell me more.” Weizenbaum had programmed ELIZA to interact in the style of a psychotherapist, and it was fairly convincing; it gave the illusion of empathy even though it was just simple code. People would have long conversations with the bot that sounded a lot like therapy sessions.

ELIZA was one of the first computer programs that could convincingly simulate human conversation, which Weizenbaum found frankly a bit disturbing. He hadn’t expected people to be so captivated. He worried that users didn’t fully understand they were talking to a bunch of circuits and pondered the broader implications of machines that could effectively mimic a sense of human understanding.

Weizenbaum started raising these big, difficult questions at a time when the field of artificial intelligence was still relatively new and mostly filled with optimism. Many researchers dreamed of creating a world where humans and technology merged in new ways. They wanted to create computers that could talk with us, and respond to our needs and desires. Weizenbaum, meanwhile, would take a different path. He’d begin to speak out against the eroding boundary between humans and machines. And he’d eventually break from the artificial intelligentsia, becoming one the first (and loudest) critics of the very technology he helped to build.

Idolizing Machines

People have long been fascinated with mechanical devices that imitate humans. Ancient Egyptians built statues of divinities from wood and stone, and consulted them for advice. Early Buddhist scholars described “precious metal-people” that would recite sacred texts. The Ancient Greeks told stories of Hephaestus, the god of blacksmithing, and his love for crafting robots. Still, it wasn’t until the 1940s and 50s that modern computers starting bringing these fantasies closer to the realm of reality. As computers grew more powerful and widespread, people began to see the potential for intelligent machines.

In 1950, British mathematician Alan Turing wrote the seminal Computing Machinery and Intelligence. Brian Christian, author of The Most Human Human, notes that this paper was published “at the very beginning of computer science … but Turing is already … seeing ahead into the 21st century and imagining” a world in which people might build a machine that could actually “think.” In the paper, Turing proposed his now-famous “Turing test” in which a person has a conversation with both a human and a robot located in different rooms, and has to figure out which is which. If the robot is convincing, it passes the test. Turing predicted this would eventually happen so consistently that we would speak of machines as being intelligent “without expecting to be contradicted.”

In 1950, British mathematician Alan Turing wrote the seminal Computing Machinery and Intelligence. Brian Christian, author of The Most Human Human, notes that this paper was published “at the very beginning of computer science … but Turing is already … seeing ahead into the 21st century and imagining” a world in which people might build a machine that could actually “think.” In the paper, Turing proposed his now-famous “Turing test” in which a person has a conversation with both a human and a robot located in different rooms, and has to figure out which is which. If the robot is convincing, it passes the test. Turing predicted this would eventually happen so consistently that we would speak of machines as being intelligent “without expecting to be contradicted.”

The Turing test raised fundamental questions about what it means to have a mind and to be conscious — questions that are not so much about technology as they are about the essence of humanity.

Computer scientists, meanwhile, were pushing forward with the practical business of programming computers to reason, plan and perceive. They created programs that could play checkers, solve word problems, and prove logical theorems. The press at the time described their work as “astonishing.” Herbert Simon, one of the most prominent AI researchers at the time, predicted that by the 1980s machines would be capable of doing any work a person could do. Much as it still does today, this idea made many people anxious. Suddenly, things that set humans apart as logical creatures were being taken over by machines.

Mirroring Language

But despite the big leaps forward, there was one realm, in particular, that proved especially challenging for computers. They struggled to master human language, which in the realm of artificial intelligence is often called “natural language.” As computer scientist Melanie Mitchell explains, “Natural language processing is probably the hardest problem for AI, and the reason is that language is almost in some sense equivalent to thinking.” Using language brings together all of our knowledge about how the world works, including our understanding of other humans and our intuitive sense of fundamental concepts. As an example, Mitchell presents the statement “a steel ball fell on a glass table and it shattered.” Humans, she notes, immediately understand that “it” refers to the glass table. Machines, by contrast, may or may not have enough contextual knowledge programmed in about materials and physics to come to that same determination. For people, she explains, it’s commonsense.

This clumsiness with human language meant that early chatbots, built in the 1950s and 60s, were tightly constrained. They could converse about some very specific topic, like baseball. By limiting the world of possible questions and answers, researchers could build machines that passed as “intelligent.” But talking with them was like having a conversation with Wikipedia, not a real person.

Shortly after Joseph Weizenbaum arrived at MIT in the 1960s, he started to pursue a workaround to this natural language problem. He realized he could create a chatbot that didn’t really need to know anything about the world. It wouldn’t spit out facts. It would reflect back at the user, like a mirror.

Weizenbaum had long been interested in psychology and recognized that the speech patterns of a therapist might be easy to automate. The results, however, unsettled him. People seemed to have meaningful conversations with something he had never intended to be an actual therapeutic tool. To others, though, this seemed to open a whole world of possibilities.

Before coming to MIT, Weizenbaum had spent time at Stanford, where he became friends with a psychiatrist named Dr. Kenneth Colby. Colby had worked at a large state mental hospital where patients were lucky to see a therapist once a month. He saw potential in ELIZA and started promoting the idea that the program might actually be therapeutically useful. The medical community started to pay attention. They thought that perhaps this program — and others like it — could help expand access to mental healthcare. And it might even have advantages over a human therapist. It would be cheaper and people might actually speak more freely with a robot. Future-minded scientists like Carl Sagan wrote about the idea, in his case imagining a network of psychotherapeutic computer terminals in cities.

And while the idea of therapy terminals on every corner never materialized, people who worked in mental health would continue to experiment with how to use computers in their work. Colby went on to create a chatbot called PARRY, which simulated the conversational style of a person with paranoid schizophrenia. He later developed an interactive program called “Overcoming Depression.”

Weizenbaum, for his part, turned away from his own project’s expanding implications. He objected to the idea that something as subtle, intimate, and human as therapy could be reduced to code. He began to argue that fields requiring human compassion and understanding shouldn’t be automated. And he also worried about the same future that Alan Turing had described — one where chatbots regularly fooled people into thinking they were human. Weizenbaum would eventually write of ELIZA, “What I had not realized is that extremely short exposures to a relatively simple computer program could induce powerful delusional thinking in quite normal people.”

Weizenbaum went from someone working in the heart of the AI community at MIT to someone preaching against it. Where some saw therapeutic potential, he saw a dangerous illusion of compassion that could be bent and twisted by governments and corporations.

Expert Systems

Over the next few decades, so-called “expert systems” started appearing in fields like medicine, law, and finance. Eventually, researchers began trying to create computers that were flexible enough to learn human language on their own.

In the 1980s and 90s, there were new breakthroughs in natural language processing. Scientists began relying on statistical methods, taking documents and analyzing linguistic patterns. Then, in the 2000s and 2010s, researchers began using what are called “deep neural networks,” training computers using the huge amounts of data that only became accessible with the rise of the internet. By looking at all kinds of language out on the web, computers could learn far faster than they would simply being programmed one step at a time. These techniques have been applied to chatbots, specifically. Some researchers train their chatbots on recorded conversations. Some put their chatbots online and they learn as they interact with users directly.

Despite these advances, contemporary chatbots — and their talking cousins, like Siri and Alexa — still can’t really “understand” concepts in the way we understand them. But even if conversational AI still lack common sense, they have become a lot more reliable, personable, and convincing. There are recent examples that make it feel as though we are living firmly in the world that Alan Turing predicted — machines fool humans all the time now. In 2018, for instance, Google revealed an AI called Duplex that can make reservations on the phone — they even inserted stutters and “um”s to make it sound more convincing. To some, this was alarming — in particular, the inability of users to tell for certain whether they were talking to a human or a machine.

Casual Therapy

This issue of transparency has become central to the ethical design of these kinds of systems, especially in sensitive realms like therapy. ELIZA may have seeded the idea of a chatbot therapist, but that idea still persists today. Allison Darcy, founder and CEO of Woebot Labs, says that “transparency is the basis of trust,” and that it informs her work at Woebot, where they’ve created a product designed to address a lack of accessible and affordable mental healthcare.

A few years back, Darcy and her team began thinking about how to build a digital tool that would make mental healthcare radically accessible. They experimented with video games before landing on the idea of Woebot, a chatbot guide who could take users through exercises based on Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, which helps people interrupt and reframe negative thought patterns. Woebot is not trying to pass the Turing test. It’s very transparently non-human. It’s represented by a robot avatar and part of its personality is that it’s curious about human feelings.

As Darcy’s team built a prototype and started learning about people’s interactions with Woebot, she says that right away they could tell something interesting was happening. As with ELIZA, people were forming emotional connections with the program, which offers high fives, sends users GIFs, and acts less like a formal therapist and more like a personal cheerleader. Darcy says her team is very conscious of the ethical questions raised by AI and she acknowledges that this kind of tech is like a surgeon’s scalpel. Used wisely, it can help people survive. Misapplied, it can be a weapon.

There are legitimate concerns around these kinds of technologies, including privacy and safety but also more complicated issues, like whether such developments might reinforce the status quo. If a chatbot is seen as a viable replacement for a human therapist, it might stall efforts to expand access to comprehensive mental healthcare. Researcher Alena Buyx has co-authored a paper about AI used in a variety of mental health contexts. She says these technologies can be promising, but that there are regulatory gaps and a lack of clarity around best practices.

Darcy is clear that she doesn’t see Woebot as a replacement for human therapists, and she thinks the potential for good outweighs the risks. She thought about this a lot when Woebot first launched. They’d been working in relative obscurity and then suddenly their numbers began to climb. Quickly, within the first five days, they had 50,000 users. Woebot was exchanging millions of messages with people each week. As Darcy recalls: “I remember going home after our first day and sitting down at my kitchen table and having the realization that Woebot on his first day of launch had had more conversations with people than a therapist could have in a lifetime.”

Joseph Weizenbaum eventually retired from MIT, but he continued speaking out against the dangers of AI until he died in 2008 at the age of 85. And while he was an important humanist thinker, some people felt like he went too far.

Joseph Weizenbaum eventually retired from MIT, but he continued speaking out against the dangers of AI until he died in 2008 at the age of 85. And while he was an important humanist thinker, some people felt like he went too far.

Pamela McCorduck, author of Machines Who Think, knew Weizenbaum over several decades. She says he burned a lot of bridges in the AI community and became almost a caricature of himself towards the end, endlessly railing against the rise of machines.

He also may have missed something that Darcy has thought about a lot with Woebot: the idea that humans engage in a kind of play when we interact with chatbots. We’re not necessarily being fooled, we’re just fascinated to see ourselves reflected back in these intelligent machines.

Comments (9)

Share

I recall a scene from the movie, THX-1138, with a computerized device that was something between a therapist and a confessional. As I recall, it was fairly ineffective perhaps symbolizing the mental health care system.

People overlook the extent to which talking to a computer is like writing a journal or reading a self-help book, and therapeutic for those reasons. And, for that matter, the extent to which therapy is useful as a journal with appointments and prompting to keep you engaged. Therapists sometimes offer helpful insights, but that isn’t always necessary in order for them to be helpful.

A mouth without a brain, eh? So, more DJT than GPT. Fascinating episode, though I have a hard time being as worried about the negative implications of this kind of AI. If a chatbot authentically helps people, what’s the harm? People do all sorts of things they think help their health that actually do nothing. We’re not outlawing salt lamps and magnetic bracelets. Of course, if negative outcomes are documented, then action would be warranted. Until then, let’s not be so Chicken Little about this amazing aspect of machine learning.

How could you possibly have an episode regarding Eliza without any reference to A.K. Dewdney’s “Computer Recreations” column in the January, 1985 issue of Scientific American. In the column, Eliza is pitted against another program, called Racter, that attempted to simulate human conversation. Hilarity ensues.

If a library you can access has a copy, you (or your listeners) may find it interesting or amusing.

When I took a BASIC Computing class in 1983 (7th Grade), we were working with TRS-80s. It was a really laid back class; the teacher normally hung out with the Computer Club geeks in the corner while the rest of us were pretty much left on our own to figure out how we can best utilize the computers in front of us.

So, I went to the local library and checked out a few BASIC programming books which featured some pretty easy games to code. I didn’t understand BASIC on a deep level, but it was fun to type in these cryptic lines of code and have something fun come out of it.

Then one day, I came to class and sat in front of my computer. Someone had installed an ELIZA game onto my rig somehow. So I answered the initial prompts ELIZA gave me and totally descended down this rabbit hole for a whole class period. It was totally intriguing in a bizarre way—it was like, part of me knew someone had programmed it, but also at the same time, it really felt like I was talking to my computer and it understood me.

I never found out who installed that game, or maybe if it had been on that computer all along, but after a few days, the program disappeared, and I got kinda sad.

The first part ties in to last year’s video game Eliza by Zachtronics which was very well received. (http://www.zachtronics.com/eliza/)

The second part reminds me of Fake It To Make It, a game about creating and distributing fake news. Terrifying in the context when even the creation of articles and managing accounts can be automated. (http://www.fakeittomakeitgame.com/)

I heard the podcast and it made me think of this completely AI instagrammer Lil Miquela who lands deals with top brands. Super interesting and I’d love to hear a full episode about it if there’s enough there for a story (or a mini-story). Just another example of some of the blurring between humans and AI and what our expectations are.

When I was a young teen/tween I played computer games like Commander Keen, Tetris, and Typing Tutor (!), while holding a two-sided conversation with myself. I was usually playing two characters (neither one of them “me” exactly), but one who was a therapist and the other a client. Probably i was working out my own shit, but it was coded in all these different kinds of people & stories. I would be playing and crying and talking, going back & forth between these characters. Something in the simplicity of the game world, and the visual distraction, and the kind of soothing rhythm of the play was itself very therapeutic, and it brought something out of me. I still associate those games, and that computer-space as this safe healing space.

Interesting article! I just recently read Turkles “Alone together: Why we expect more from technology and less from each other” and it led me to refer to these mechanical beings as pseudo beings. In parallel with Turkle, I feel that “Relational digital artifacts; pseudo-beings (AI, robots, avatars and personas), from a point of view that values the richness of human relationships, they don’t make sense at all:” https://touchedspace.wordpress.com/2019/11/20/selfies-inexplicable-companions/