Margarine is yellow, like butter, but it hasn’t always been. At times and in places, it has been a bland white, or even a dull pink. These strange variations were a byproduct of a 150-year war to destroy margarine and everything that it stands for. During this epic fight for survival, margarine has had to reinvent itself, over and over again.

Margarine traces all the way back to French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte III. In the 1860s, France was heading towards a war with Prussia, and Napoleon had to find a cheap way to feed the entire French navy. In particular: he wanted a replacement for butter. In response, French chemist Hippolyte Mège-Mouriès came up with a mixture of beef caul fat, which he reduced to an oil and mixed with milk and salt. The first margarine was not vegetarian, but it had a lot going for it, including being cheap and lasting for a long time. Still, it was slow to take off.

Under the guidance of the deceptively named United States Dairy Company, margarine was introduced to Americans in the 1870s. And it gained traction because butter was expensive at the time, and if you didn’t have money, your alternative was buying rancid butter. Seriously: there was a product called “renovated butter,” which was downright disgusting — a mixture of leftover and bad butters and creams mixed together.

Under the guidance of the deceptively named United States Dairy Company, margarine was introduced to Americans in the 1870s. And it gained traction because butter was expensive at the time, and if you didn’t have money, your alternative was buying rancid butter. Seriously: there was a product called “renovated butter,” which was downright disgusting — a mixture of leftover and bad butters and creams mixed together.

By 1882, New York state was producing over 20 million pounds of margarine per year. Dairy farmers, of course, were less than thrilled. The butter lobby fought back, and big butter had deep pockets. In the 1880s, dairy partisans spread disinformation about how margarine was made and what it was made from. The stories were effective. Soon, politicians across America began passing laws to try to stop the malicious spread of margarine. In 1884, New York state even tried to pass a full ban on margarine.

Unable to ban margarine outright, a new tactic emerged: making margarine unattractive so people wouldn’t want to eat it. Across the country, states passed laws that required margarine to be dyed, so it didn’t look like butter. Some states toyed with red or even black margarine. But pink became the most prominent. Laws about the color of margarine were on the books until the 1950s and ’60s in many states. And they lingered in places like Quebec into the early 2000s.

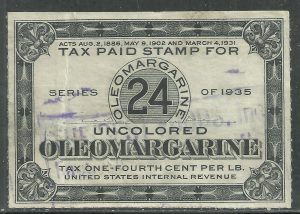

Finally, Congress got involved and tried to kill margarine once and for all. In 1886, a bill was introduced that would require a ten-cent tax on every pound of margarine. A big tax that would definitely kill the margarine industry. Supporters of the bill pulled out all the rhetorical stops, and put it in moralistic terms, saying margarine was unnatural and industrial, while butter was pure and beautiful. Here’s a quote from House member David Henderson of Iowa:

You will find butter in the Bible from Genesis to Revelations. You will hardly find a book in the Bible that does not speak of butter. The article came into use before profane history was written. Milk and butter have been the food of man from time immemorial, and you do not need medical certificates or the resolutions of boards of trade to tell you that butter is a wholesome article of food.

In contrast, his view on margarine was unsubtly scathing:

Now, let me give you the first record I find of oleomargarine. In the fourth act of the play of Macbeth, where there was a little cotillion of witches, I find oleomargarine completely described.

Just to be clear: margarine is not, in fact, made from eye of newt and toe of frog in some witches’ cauldron. Still, there was a lot of talk about butter being pastoral and ancient. It didn’t matter that margarine was just a spread you put on toast. It had come to represent so much more. Ultimately, the Margarine Act passed. But the tax was reduced, and the industry survived. Margarine hung on, then came back in force.

In the early 20th century, a new process called hydrogenation made it possible to use vegetable oils in margarine instead of beef and pork fat. Sure, margarine was still a processed mystery food, but now it was a processed mystery food that had vegetables. Margarine also got a boost from the two World Wars, with butter in short supply. In the postwar era, it started to gain a new and better reputation.

For years, margarine sales climbed, and ads flooded the airwaves, telling consumers that margarine could do all the same stuff as butter at a fraction of the price. Political opposition to margarine slowly melted away. And by 1967, American laws regulating margarine color had been repealed.

And as diet culture changed, margarine became a health food. A consensus had formed among food scientists that saturated fats were the root cause of American heart disease. Suddenly, butter was a bogeyman and margarine took over the dairy aisle.

But while nutritionists were singling out animal fats, they weren’t paying attention to the problems with vegetable oil. The hydrogenation process created a new kind of fat called “trans fat.” By the early 2000s, pretty much everybody knew that trans fats were bad for you and that saturated fats were a lower risk. Margarine producers largely got rid of hydrogenated oil, but it was too late. Today, Americans eat a lot more butter than margarine. Pandemic baking in particular has led to a recent spike in consumption.

But this is not margarine’s final chapter. Recently, margarine has become tied to another major food trend. As more people cut animal products out of their diet, there’s been a rise in “plant-based butters.” These butters are marketed with pastoral names like Earth Balance. But if you look at the ingredient list, they’re pretty similar, except plant butters are vegan while some margarines contain traces of dairy. This plant-based revival is the latest evolution for margarine, a way for it to latch onto another cycle in our food culture. Margarine keeps riding this pendulum of taste, of what we think is good for us or bad for us. And along the way, it’s been a miracle of science, then a villain, then a war hero, and a health food, but above all: it’s been a survivor.

Comments (10)

Share

When Newfoundland joined Canada in 1949, the production of margarine was already banned in the rest of Canada.

Margarine, manufactured by the Newfoundland Margarine Company, was so important in the soon to be new province that it was explicitly protected in the terms of the agreement to join the confederation of Canada.

So the ability to manufacture and market margarine was part of the terms of creating the new Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador and is historically interwoven in the history of Canada.

Referring to these “plant based butters” as any form of butter shows exactly why we need and have always needed some way to distinguish butter from its alternatives.

Thankfully it is mostly just dealt with by labelling requirements in most of the world. No need for silly colour laws.

Love the humor Chris brought to this unexpected history of something we eat on the reg! For some reason, I esp liked when he said something to the effect of, yes that’s the second butter historian. I totally know how to do my job. 😁 🧈 💛

I am getting ContraPoints vibes on the production of this episode. The chapter title voice has got to be an intentional homage, right?

I was wondering the same! Maybe a super subtle reference to the “spread” of BreadTube? 😆 Or maybe I just want to hear more Natalie and confirmation bias?

My mother, Laura Patton (1920-2014), told us the story of an Oregon State Legislator who opposed the state law banning the sale of yellow margarine. That Legislator stood at the podium in the State Capitol in Salem and went through the ridiculous, messy, and very time-consuming process of working a capsule of yellow dye into a batch of white margarine. That was the end of that law in Oregon.

I can’t believe you didn’t tie this back to the episode about romance novels. After all, Fabio doing the “I can’t believe it’s not butter” commercial was a classic!

I’d have to call this one a bit random for design, but I enjoyed it as always!

Love the tie-in to Fabio with your episode on romance novel covers. It didn’t come through on the audio version, but I see the website has it covered!

There’s an old comedy radio show called “The Great Gildersleeve” now available online (which was coincidentally the first sitcom spinoff ever, as Gildy used to appear on the “Fibber McGee and Molly” show) featuring the domestic antics of Gildy and his family. It was sponsored by “Parkay Margarine, the wholesome spread your family will love!” I can’t prove it, but I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Gildy’s sweet and wholesome daughter was named Marjorie.

Thanks! One of my earliest memories was squeezing a packet of margarine to add the red dye in our kitchen in Winnipeg in the early 60s. I remember that the dye was in a packet inside the bag of margarine that you could snap to release. Then you started squeezing and squeezing which seemed to go on forever before you ended up with something that still didn’t look anything like butter in the end . It was an early lesson for a kindergarten aged child that adults sometimes did things that didn’t make any sense!