Urban worldbuilding is at the heart a lot of speculative fiction classics. But authors don’t develop the history, geography and ecology of their imaginary worlds in a vacuum. Often, their creations reflect present (or predicted) conditions right here on Earth.

Space Fiction: Trantor as Ecumenopolis

In the 1940s, science fiction author Isaac Asimov introduced his readers to Trantor, a huge and densely-packed urban planet at the center of the galaxy. “All roads lead to Trantor, and that is where all stars end,” reads one of his passages. This spatial nexus featured prominently in two of his most famous series: Foundation and Galactic Empire.

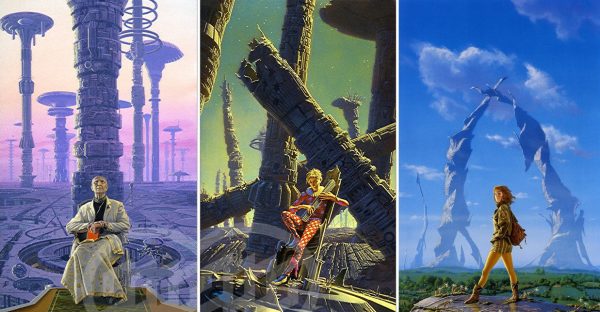

One vision of this sprawling planetary metropolis is shown on a series of 1990s covers by artist Fred Gambino for Foundation, Foundation & Empire, and Second Foundation. In painting a cityscape across multiple books, Gambino hints at Trantor’s incredible density and scale.

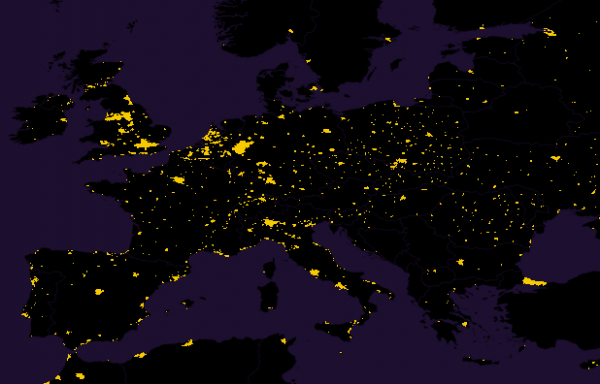

About 30% larger than Earth and covered in buildings, Trantor is what Greek city planner Constantinos Doxiadis would come to call an “ecumenopolis” (Greek for “world city”) in the 1960s. Fascinated with megacities both real and imagined, Doxiadis also predicted Europe would eventually become an “eperopolis” (“continent city”) as its population centers continued to spread, connect and overlap.

In Asimov’s universe, Trantor’s 750 million square miles of surface (plus underground space) would come to house 45 billion people. Naturally, this world city could not be self-sufficient. It would have to be supplied by other planets devoted to farming, reducing the need to produce food on Trantor itself (spoiler alert: this would lead to trouble for this world city down the line). In many ways, Trantor is an extreme extrapolation of ordinary, single-continent urbanization — a familiar set of urban/rural dynamics envisioned on an interplanetary scale.

Cyberpunk: The Sprawl as Megalopolis

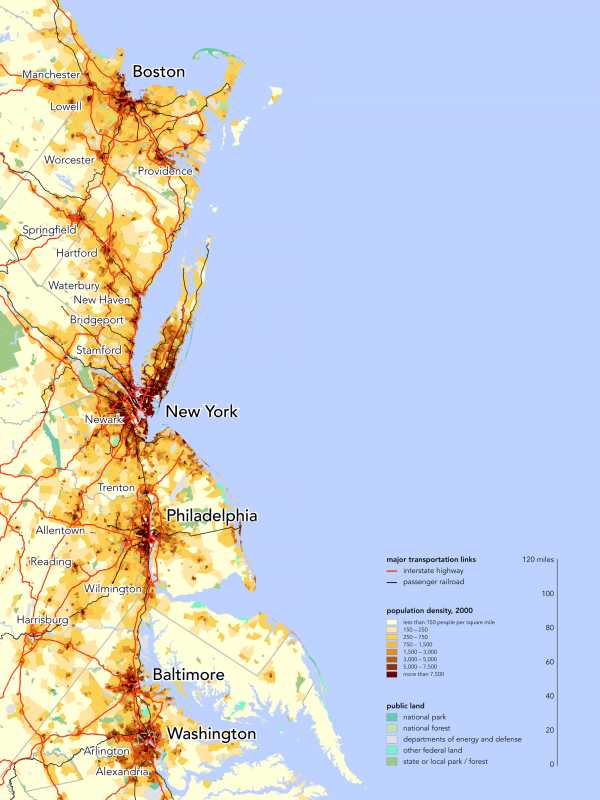

Back here on Earth, we may be a few centuries (or millennia) away from an ecumenopolis (or even a eperopolis), but one of cyberpunk pioneer William Gibson‘s 1980s megacity visions is already becoming a reality of sorts. The Northeast Megalopolis (or: Bos-Wash Corridor) is not yet covered in domes like his Sprawl, but urban centers spanning from Boston to Washington, D.C. are growing ever more interconnected.

In Gibson’s Neuromancer, Count Zero and Mona Lisa Overdrive, the Sprawl is a colloquial name for the Boston-Atlanta Metropolitan Axis (BAMA). The fact that the title of this trilogy takes its name from the place (the Sprawl Trilogy) is perhaps revealing — the books are highly focused on elaborate world-building, centered on this megalopolis.

The term “megalopolis” (Greek for “great city”) originated in the early 1900s and was used on and off in reference to urban over-development. French geographer Jean Gottmann popularized the word in the 1960s when he published Megalopolis: The Urbanized Northeastern Seaboard of the United States. While noting they remained technically discrete, Gottmann found that the chain of cities across this region had taken on characteristics of a giant supercity with overlapping suburban zones.

Gibson’s depictions of the gritty, ultra-urban environment this megaregion could become are too compelling to paraphrase or summarize, but this quote from Count Zero starts to paint a picture:

“Bobby crawled down behind him, into the unmistakable signature smell of the Sprawl, a rich amalgam of stale subway exhalations, ancient soot, and the carcinogenic tang of plastics, all shot through with the carbon edge of illicit fossil fuels …. The Sprawl’s patchwork of domes tended to generate inadvertent micro-climates; there were areas of a few square city blocks where a fine drizzle of condensation fell continually from the soot-stained geodesics, and sections of high dome famous for displays of static-discharge, a peculiar variety of urban lightning.”

Gibson’s Bridge Trilogy (set in the western United States) likewise takes its name from a physical locus. In Virtual Light, Idoru and All Tomorrow’s Parties, the structurally compromised San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge no longer serves to shuttle vehicles across the water — instead, it houses people and plays a central role in connecting characters.

Fantasy: New Crobuzon as Megacity

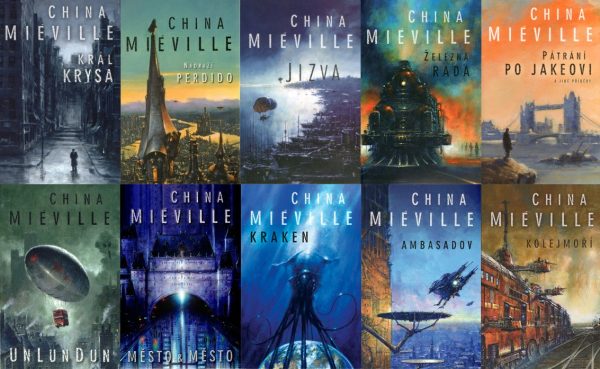

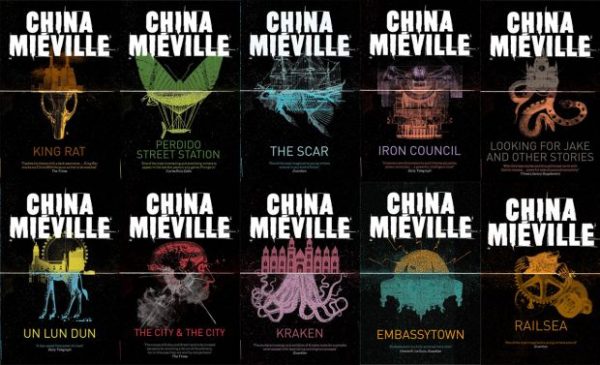

Meanwhile, no collection of stellar urban world-builders would be complete without some mention of China Miéville, who writes at the intersection of science fiction, steampunk, fantasy and horror. His The City & the City is a story of “twin cities” that physically overlap in uncanny ways, occupying the same space at the same time. His other works include The Rope is the World, a short story of life inside an old space elevator spanning from Earth to orbit, as well as Embassytown, set on an alien planet and in which built environments are central. Those and tales like Un Lun Dun, set in an alternative London, have led some to characterize his stories as works of “urban surrealism.”

And then there are Miéville’s collection of novels set in the fictional Bas-Lag, which each intersect at one physical point: the city-state of New Crobuzon. The New Crobuzon Series started with Perdido Street Station, written in 2000 and titled after the city’s central train station. While elements of this dirty and sprawling but enthralling megacity have reminded readers of places like Cairo, New Orleans and Victorian London, any terrestrial comparison fails to do it justice:

“A city unconvinced by gravity …. New Crobuzon, this towering edifice of architecture and history, this complexitude of money and slum, this profane steam-powered god.”

According to the author, “New Crobuzon is highly influenced by Brian Aldiss’s The Malacia Tapestry and Tim Powers’s The Anubis Gates, but they’d permeated me so deeply I was initially less conscious of them than of other influences.” Ultimately, to understand the place, it is worth reading Perdido Street Station, The Scar and The Iron Council, and perhaps the sources of inspiration mentioned above by Miéville as well.

The books of the New Crobuzon Series are all set in the same strange world and anchored by the same singular city-state. As the latter two branch out to explore other places, structural settings remain central — Iron Council stars a marvelous mobile arcology on rails and The Scar features epic descriptions of a massive flotilla habitat:

“They were built up, topped with structure, styles and materials shoved together from a hundred histories and aesthetics into a compound architecture. Centuries-old pagodas tottered on the decks of ancient oarships, and cement monoliths rose like extra smokestacks on paddlers stolen from southern seas. The streets between the buildings were tight. They passed over the converted vessels on bridges, between mazes and plazas, and what might have been mansions. Parklands crawled across clippers, above armories in deeply hidden decks. Decktop houses were cracked and strained from the boats’ constant motion.”

Many amazing speculative megacities can be found in other mediums as well, from comic books to television shows and feature films. But there is something special about stories told only text (or audio).

As Miéville alludes to in the interview above, a certain magic can happen at intersection of an author’s description and a reader’s interpretation — these can come together in generative ways, shaping surreal urban landscapes from both memories and imagination.

Comments (2)

Share

I really like this article, but I feel like it’s missing a final act. I’d love to hear your take on what these fantasies ultimately say about us.

Another entry: David Alexander Smith’s shared world Future Boston: The aliens dropped their hypergate terminal in Boston Harbor, unilaterally making Boston the embassy to the galaxy. A century or few (I forget) later, the city has been built up into a cube of mixed human and alien building materials, inhabited by all the species who’ve come to visit — and, of course, many many humans.

There’s also Niven’s “arcologies”, and I think Brunner did some similar ideas. Of course, any of these solid-mass concepts would be seriously challenged by square-cube issues, notably air and water movement, and especially heat dissipation.

And then there’s space habitats, from Clarke et al onward….