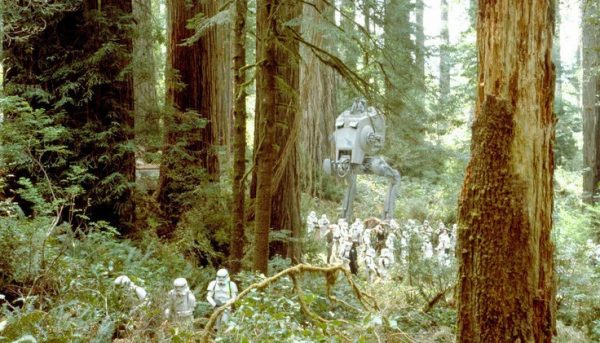

The unveiling of new US Space Force uniforms has led some spectators to observe that these green, tan and brown outfits would serve well on battlefields like the forest moon of Endor, a fictional setting from Star Wars (in which white-clad stormtroopers really stood out).

Defenders of the design note it is meant to be worn by servicepeople on the ground, not in space. Still, this choice of pattern does raise questions, like: why return to a classic, 20th-century style consisting of splotchy woodland colors rather than something more current or even potentially futuristic-looking, such as pixelated camouflage?

![]()

From Blocks of Colors to Blotchy Camo

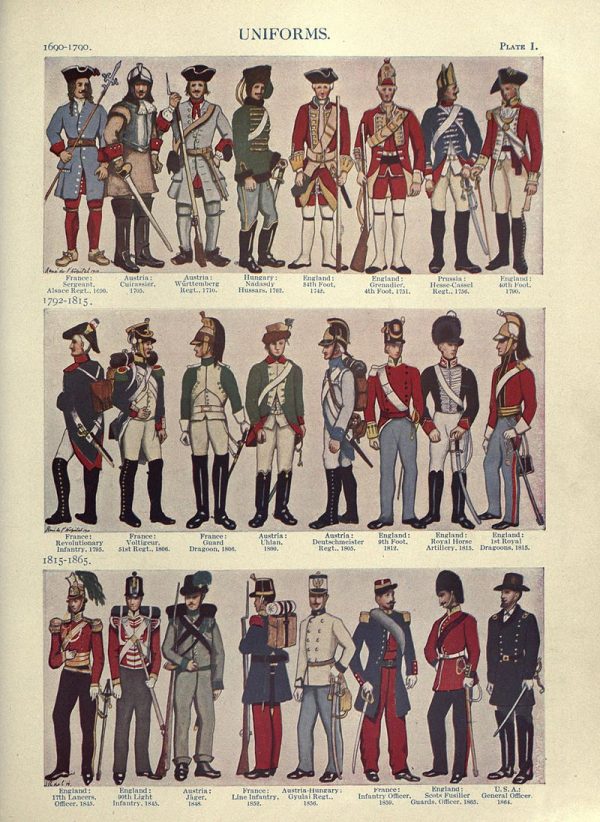

Historically, large armies were often clad in brightly colored uniforms, but the development of new weaponry like long-range rifles and the advent of aerial attacks gave rise to new blending approaches, starting with neutral monochromatic solutions that matched natural setting.

Early snipers began to wear camouflage, but in World War I much of the focus was still on masking larger things, like structures and vehicles. Specialists covered buildings in naturally colored mosses, paints and netting. Some counter-intuitive solutions were also developed, like “dazzle camouflage,” which was not meant to hide ships as such but rather to make their distance, direction and speed hard to pin down.

As World War II unfolded, concealment techniques expanded. Armies employed everything from fake trees (that soldiers could hide inside) to inflatable prop tanks. Specialized “deception units” were critical for misdirecting Axis forces at key moments, including the Allied landing at Normandy. Some uniform camouflage was employed as well, but there were concerns about friendly fire in the wake of D-Day — seeing and recognizing allied forces was understood to be critical, too.

Modern camouflage as we know it evolved in fits and spurts. While many soldiers continued to wear single-color outfits, more and more nations began experimenting with multi-color garbs that would help their troops blend in with their surroundings more effectively.

Out of the mid-1900s came theater-specific garbs, too, for forest, jungle, desert and snowy environments, generally using splotches of color that curved around each other in overtly naturalistic ways.

For the US military, this trajectory culminated in the Battle Dress Uniform. The BDU design was widely deployed in the 1980s and is still found around the world today, in some cases because US surplus stock was sold off or shipped abroad as part of security assistance packages.

The Computer-Age Rise of Pixelated Designs

Around the turn of the 21st century, a relatively radical new approach began to take hold: replacing organic blotches with rectilinear boxes of color. This digital-age camo took its cues not from nature but the computerized world, bolstered by psychological theories about how humans parse what they are seeing both up close and at a distance.

In practice, some of these blocky patterns have fared better than others. One United States Office of Naval Research study concluded that the early 2000s MARPAT design (a Marine camouflage pattern following in the footsteps of a Canadian Forces precursor) took two and a half times as long to detect as more traditional variants.

A so-called Universal Camouflage Pattern (UCP) was adopted by the US Army around that same time, but this one showed less promise from the start. It was chosen from a narrow set of options and went through limited field testing. When it was nonetheless produced and distributed, the design was ultimately criticized by troops who were actually using it on the ground, particularly in desert settings like Afghanistan. Billions of dollars were spent before the pattern was effectively abandoned.

The Return to Organic Approaches

Combining both successful precedents and test data, the Operational Camouflage Pattern that has come to replace the UCP and other options looks a lot like older and more organic precursors.

Whereas a lot of creative theoretical arguments drove the digital aesthetics of pixelated solutions, the OCP was based on a more intensive design process followed by extensive testing. It offers a simple and clear lesson for anyone looking to develop a new uniform: create drafts, try them out and see what best goes unseen.

Space Force, meanwhile, as a military service branch within the Department of the Air Force, has also adopted the OCP — it might not be ideal for wars out among the stars, should do just fine on Earth.

Leave a Comment

Share