Dotting the mountains of the Scottish Highlands, picturesque dwellings offer hikers and cyclists a chance to rest, relax and spend the night, free of charge. This long-standing network of retreats is maintained primarily by volunteers organized by the Mountain Bothies Association, a Scottish charity which works with landowners to care for the structures. Today, almost all bothies sit on privately-owned land — the MBA itself only owns one building in the network they oversee.

Though more concentrated in Scotland, bothies can be found in Northern England, Ireland and Wales as well. Historically, the term “bothy” was mainly used to describe modest dwellings for itinerant workers, but the meaning has expanded to include this class of retreat.

Many of the structures in the current bothy network were originally built for other functions, serving as post offices, schools, wilderness retreats, coastguard stations and more. Some sit up in the mountains, others along private beaches or on cliffs overlooking the ocean.

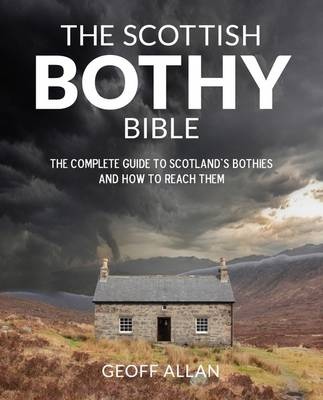

“Bothying” started to become popular in the wake of early 1900s rural depopulation. Initially, walkers would simply hole up in deserted buildings, with or without explicit permission. And for many years, finding and staying in these was a largely informal process — location information was passed around by word of mouth. Then, in 1965, the MBA was formed to help protect the structures from decay and ruin, preserving them for present and future generations of hikers. In recent years, MBA group began putting maps up publicly online. Books like The Scottish Bothy Bible have raised awareness, too. Structural shifts in land accessibility played a critical role as well.

As England and Wales began implementing their Countryside and Rights of Way Act in the early 2000s, increasing regional “freedom to roam,” Scotland decided to take things a step further. In 2003, the country passed its own Land Reform Act. This did a number of things, but, first and foremost, it codified a long tradition of public access. Basically, if people are respectful of other people and property, they can roam even more freely on private land up north.

Because most bothies are located on private land, people using them are expected to be conscientious of the structures and their surroundings. A code of conduct governs behavior — visitors should come in small groups , for instance, unless they seek out specific permission. They should also avoid damaging live trees on owned property and, if possible, leave kindling for the next folks (some owners restock wood, too).

Because most bothies are located on private land, people using them are expected to be conscientious of the structures and their surroundings. A code of conduct governs behavior — visitors should come in small groups , for instance, unless they seek out specific permission. They should also avoid damaging live trees on owned property and, if possible, leave kindling for the next folks (some owners restock wood, too).

Travelers hoping for a hotel-like stay (or even hostel-style environment) should be aware, though, warns the MBA: “When going to a bothy, it is important to assume that there will be no facilities. No tap, no sink, no beds, no lights, and, even if there is a fireplace, perhaps nothing to burn. Bothies may have a simple sleeping platform, but if busy you might find that the only place to sleep is on a stone floor.” Some, however, do feature stoves, insulation or even little libraries.

Free overnight shelters are by no means limited to the British Isles — backcountry huts can be found in countries including Sweden, Norway, Russia, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States.

Small mountain shacks in Switzerland, for example, provide emergency shelter, but they are not particularly spacious. Finland has an array of more robust cabins, though mainly maintained by the government. Partially enclosed Adirondack lean-tos in Upstate New York help keep out some rain and snow, but they are sited on public land.

So bothies are not a unique phenomenon, but do differ from a lot of shelters that are purpose-built and municipally run. They represent a creative way to reuse old buildings, too, engaging landowners as well as volunteers who are invested in nature (and wilderness adventures). And they thrive in part on a particularly permissive approach to land use, enabling people to wander in the truest sense of the word.

Comments (3)

Share

There are also no trespassing laws in Scotland, making it legal to pitch a tent just about anywhere.

I’ve had some very cold nights in bothies. They are a great resource and all credit to the volunteers who maintain them.

This reminds me of Colorado’s huts. About half our land is public, too. I hope we keep it this way!

http://www.oriconline.org/where_to_stay/huts_yurts_cabins.htm