In 1975, an artist in the Lower East Side of Manhattan began clearing debris and building a garden on the site of a demolished building. Inspired by the sight of children playing in a basement pit behind an adjacent apartment, Adam Purple started crafting a green space that would ultimately grow to span 15,000 square feet and become known as the Garden of Eden.

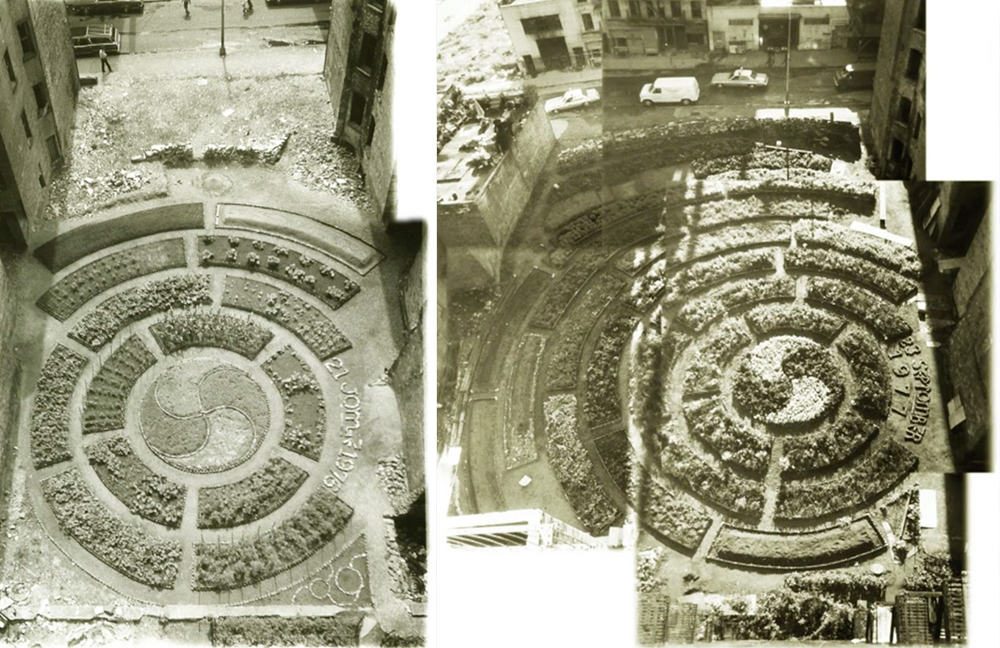

Turning brick rubble into pathway pavers and creating topsoil with potash from burned wood and manure hauled from Central Park, Purple shaped his idyllic green space into an expanding circle. At first, the shape seemed compressed by bordering structures. Then, almost as if driven by its expansion, neighboring buildings began to come down, one after the next, each of their lots incorporated into the garden’s ever-enlarging series of concentric rings.

More than a recreational park, the garden was productive, sprouting cucumbers, asparagus, cherry tomatoes, black raspberries on walls and dozens of fruit-bearing trees. Purple saw it as a work of art and an expression of basic human rights and needs, grown by and for the community, drawing its materials from discarded remnants of city dwellers. Adam and his partner Eve, inspired by nature-loving writers such as Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson, were seen by some as strangers and outsiders, but viewed by many locals as green-minded civic visionaries.

“It seemed impossible for a garden to exist in a place like that, the soil poisoned by chemicals, the neighborhood littered with rubble and trash, yet there it was, by something of a miracle. Spring, summer and fall, Adam and Eve tended to The Garden, planting and trimming various flowers, fruits and vegetables, occasionally taking a break to enjoy the shade of a black walnut tree or to pluck a plump red strawberry.”

— Derik Dermaier

Purple and those who helped him employed simple implements to aid in construction, including rakes, hoes, shovels, wheelbarrows, sledgehammers and hacksaws. His apartment was filled with salvaged scraps, from hinges, screws, wood and gravel to sheets of iron and pieces of porcelain tubs. He developed usable soil from a combination of clay from bricks, potash from wood and excrement from horses.

The fruits of their labor were never recognized officially by New York City, which unveiled plans for low-income housing on the five building sites spanned by the garden in the early 1980s. The Storefront for Art and Architecture produced a design that would incorporate the garden into the project, but it was insufficient to save the space. Purple himself also attempted to sue the city on the basis that they were destroying a work of art, but likewise to no avail. Just over a decade after it was started, bulldozers were sent to tear it down the Garden of Eden.

Born David Lloyd Wilkie, but nicknamed for the color he always wore, Purple was a journalism student and army veteran who passed away in September of 2015. His personal life (and death) were shrouded by allegations of abuse and neglect; there was a dark side to Purple, according to a series of Village Voice articles following his demise.

The Garden of Eden project itself was, in many ways, a cutting-edge critique of top-down urban planning, as epitomized by the Garden City movement. The project reflected many citizen-oriented, common-sense ideals as championed in Jane Jacob‘s influential The Death and Life of Great American Cities, published in 1961. While it was ultimately destroyed, the Garden’s legacy remains, in part through the ongoing evolution of the guerrilla gardening movement.

Comments (2)

Share

I once visited the Garden of Eden in Lower Manhattan, and it happened to be the day that the bulldozer came in mid-September 1985 to destroy some of the walls protecting the garden, a few months before the garden’s demise the following January. Plenty of locals were on hand that day to bear witness to the garden’s loveliness as a unique community space. Also on hand were about a dozen policemen, a number of onlookers, as well as a contingent of folks across the street who were demonstrating in favor of dismantling the garden for low income housing. I took some photos that day, and posted 7 of them to the 99% Invisible Flickr page: https://www.flickr.com/groups/2689011@N23/

It is sad to know the beautiful garden to be razed in 75 minutes after a decade of upkeep. What a pity! :(