In 1911, the US Forest Service was tasked with putting out fires as fast as possible, a mandate driven in part by a huge fire that burned across a massive section of United States the year before — a devastating blaze that reshaped how Americans approached firefighting.

The Great Fire of 1910 is believed to be the largest fire in US history, earning it nicknames including the “Big Burn,” the “Big Blowup” and the “Devil’s Broom Fire.” It swept through millions of acres in northwestern states including Washington, Idaho and Montana. Ships that were hundreds of miles out at sea had trouble navigating due to the haze. People as far east as New York reported seeing smoke. Close to a hundred people died in the fire, including some firefighters.

There had been talk of disbanding the Forest Service for years leading up to this fire, but this blaze cast firefighting in a new light. The agency received an increased budget and started hiring a lot more people. The “Big Burn” helped crystalize the idea that fires needed to be fought.

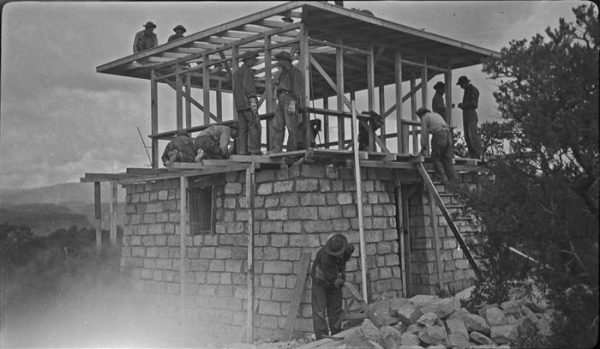

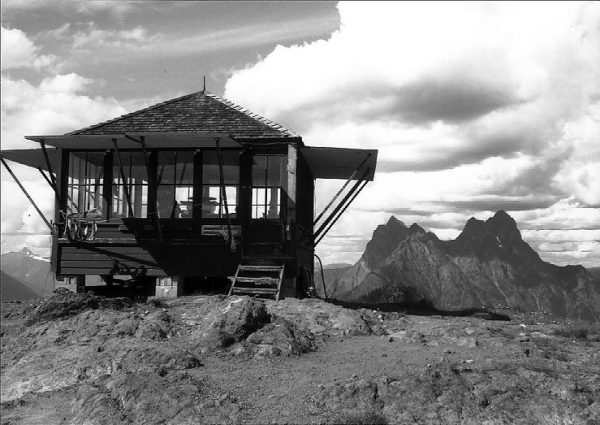

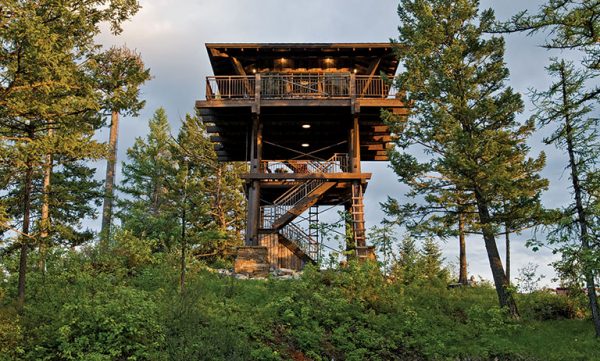

Early fire lookout spots were scrappy affairs — often simply camps erected at “patrol points” accessed by horseback trails, or “crow’s nests” bolted onto existing trees. Later came stand-alone observation structures ranging from simple rooms sitting on stone outcrops to extremely tall towers accessed by ladders and spiral staircases. Live-in cabins followed, providing accommodations for lookouts. By the 1930s, over 5,000 fire towers had been built around the country.

Some were constructed by the Civilian Conservation Corps, one of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s more popular New Deal initiatives. The CCC put people to work in the Depression era on various projects. Among these was the construction of fire towers on remote hills and mountains as well as the creation of rural roads reaching out to them.

A USFS Fire Lookout using an Osborne Firefinder in California, image by Charles White

Fire lookouts would climb up and look out for smoke, using tools like the Osborne Fire Finder — a device that could be sighted along to determine the direction and approximate location of fires (particularly helpful when multiple towers could triangulate the source).

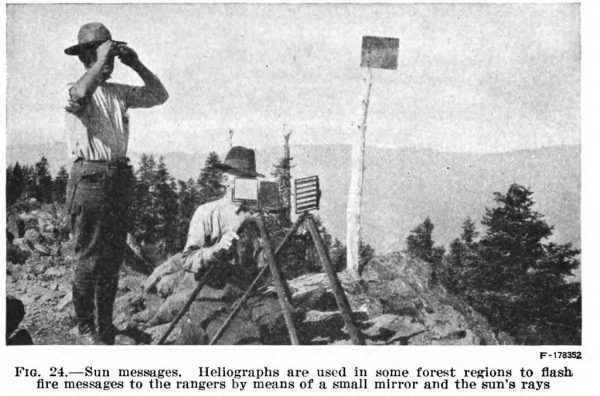

In the early days, tower lookouts relayed information using low-tech devices like heliographs. These were essentially mirrors that reflected sunlight to send Morse code signals to other towers or stations below. Some towers even alerted rangers to fires using homing pigeons, which could help overcome the limitations of line-of-sight communication. Later came telephones and then, by the time radios were common, the tower system was winding down, though some were still manned.

Being a fire lookout was lonely work, or peaceful, depending on one’s perspective. Creatives like novelist Jack Kerouac, who authored Big Sur and On the Road among many other books, appreciated the time alone. He was paid to be a lookout one summer in the 1950s on Desolation Peak and got a lot of writing done during his stay.

Today, a number of towers are still actively in service — even now, satellites are slow and cell service can be spotty in rural areas. Most, however, have been abandoned or taken down for scrap, or deconstructed and moved for public display. Some, though, have been converted into houses and others can be rented out by the public, and (by design) they naturally tend to have fairly stunning views.

Meanwhile, approaches toward fighting fires have changed somewhat, too. These days, there is still interest in spotting them early, but the response isn’t always to deploy teams and put them out. Now, spotting a fire is just a first step in deciding whether or how to intervene.

Comments (3)

Share

Nice Article! I think the game Firewatch deserves a mention, since it takes place in one of those towers and doing a great job at showing the isolation.

Thanks for a great article.

Another interesting piece of the Forest Service’s impressive efforts to improve fire detection in the 1930’s was a project directed by W. B. Osborne, who also developed the fire finder mentioned in the article, to collect high resolution panoramic photos from every lookout in Oregon and Washington. Osborne designed a custom rotating photo transect camera for this project and several field crews spent 3 years gathering photos from over 800 sites. The photos are now housed in the national archive in Seattle Washington. Several hundred of the photos from Oregon have been scanned and can be viewed at this website: http://maps.tnc.org/osbornephotos/

The photos are a great resource for visualizing the often dramatic changes in the forest caused by 80 years of fire suppression.

Just a little note by way of correction: Jack Kerouac spent the fire season of 1956 on Desolation Mountain as a firewatcher, the year prior to the publication of ‘On the Road’. By the 1960s, his social situation certainly bore little resemblance to his time as a lonely watchman!