American cities tend to follow grid systems, and yet these grids also regularly deviate from predictable patterns in ways that can seem inexplicable at times. In places like Detroit, one can begin to unpack such complexities and contradictions by examining critical moments in the history of a place. In turn, understanding the development of one city can also help frame the growth of American cities more broadly.

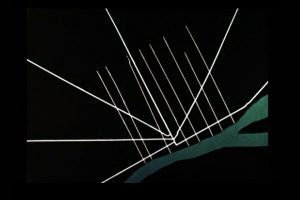

This 1960s educational video starts out with a lay of the land: “To an overhead observer, the street pattern of Detroit presents a strange mosaic of conflicting systems, which seem to start and end with no apparent reason and have no relation to each other. However, the twists and turns have their historic explanations.” Indeed, the narrators proceed to pick apart sets of city streets, separating them out by time, type and orientation to explain the history of this built environment.

Consider the graphic above as a starting point: note the different orientations of streets — some run parallel (or perpendicular to) the water to the southeast; others run east/west or north/south; and still others run against both of these conventions. Each of these can be explained in turn if examined one convention at a time, traced over centuries of settlement and expansion.

Trading Trails into Spoke Streets

In 1701, the French landed in what would eventually become known as Detroit. Their settlement was protected on three sides by water and the few main streets they established paralleled the shoreline by the Detroit River. Additional trails were worn through the surrounding wilderness, though — and these initially informal trade routes would eventually become major spoke streets of the city.

In 1701, the French landed in what would eventually become known as Detroit. Their settlement was protected on three sides by water and the few main streets they established paralleled the shoreline by the Detroit River. Additional trails were worn through the surrounding wilderness, though — and these initially informal trade routes would eventually become major spoke streets of the city.

Over the course of the 1700s, French rule gave way to British and then American. After the Great Fire of 1805 burned the city to the ground, however, the core of the city had to be rebuilt.

Equilateral Triangles as Downtown Core

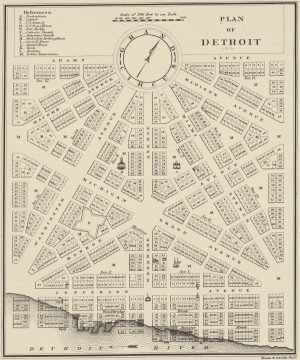

Instead of rebuilding the downtown as it had been, however, a new plan was established for the 1800s — one that would ready the city to be a metropolis of the future. The plan was based on the unit of an equilateral triangle 4,000 feet on each side. This, in turn, was bisected by perpendicular lines that would intersect in the center. Parks would be established at those intersections as well as the outside points of the triangles. The system was repeatable by design — the triangles could be flipped and replicated outward indefinitely.

Instead of rebuilding the downtown as it had been, however, a new plan was established for the 1800s — one that would ready the city to be a metropolis of the future. The plan was based on the unit of an equilateral triangle 4,000 feet on each side. This, in turn, was bisected by perpendicular lines that would intersect in the center. Parks would be established at those intersections as well as the outside points of the triangles. The system was repeatable by design — the triangles could be flipped and replicated outward indefinitely.

This plan was opposed due to its odd angles and the way it redrew property lines, leading it to unfold only over a limited central area before being abandoned. The results of the Woodward Plan are partial and cover just a small section of the current downtown. What little was built, though, was also tied into the ever-more-official streets radiating out from the city — those ones that had been trading trails.

French Farms into Shoreline System

Meanwhile, old French farms in the area had tended to be long and thin strips running perpendicular to the water (in order to give irrigation access to farmers). Over time, the boundaries of these farms became natural paths for roads largely running perpendicular to the water (often named after the farmers owning adjacent land).

Meanwhile, old French farms in the area had tended to be long and thin strips running perpendicular to the water (in order to give irrigation access to farmers). Over time, the boundaries of these farms became natural paths for roads largely running perpendicular to the water (often named after the farmers owning adjacent land).

The farmers were fine with border roads but resisted cross-streets through their property. As a result, there are many jogs and bends in roads parallel to the water. Also, this system of long streets extending out from the water complicated the city, intersecting oddly with sections of the downtown core as well as the spoke streets.

Cardinal Directions into Grid System

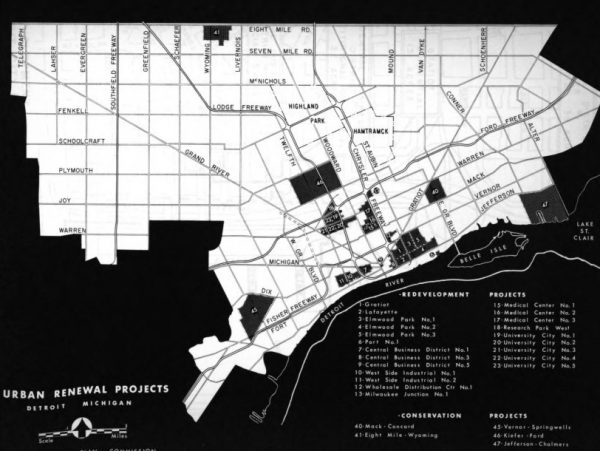

Eventually, further peripheral development was shaped by overlays of conventional north/south and east/west grid systems, deployed in square-mile blocks as the city grew outward away from the water. These run at odd angles to all of the preceding plans.

Eventually, further peripheral development was shaped by overlays of conventional north/south and east/west grid systems, deployed in square-mile blocks as the city grew outward away from the water. These run at odd angles to all of the preceding plans.

The first such road, heading straight west from City Hall, was called 0 Mile (later: Ford), and established the basis of the ‘Mile Road’ system moving northward (1 Mile, 2 Mile and so forth). The east/west roads are generally shorter-blocked and evolved with commercial occupants while the north/south ones became primarily residential. This system once again had to contend with existing conditions, particularly where it was crossed by spokes or intersected with the shoreline grid.

At a Crossroads of Urban Designs

Many of the traffic problems found in Detroit exist at places where different approaches (like the grid and shoreline systems) intersect, creating strange junctures or forcing elaborate turns. To minimize complications, subsequent additions have been made to conform wherever possible — even more recent freeways of the mid-1900s mainly ended up following systems laid out long in advance, paralleling spoke streets, shoreline or cardinal grids.

In the end, Detroit’s layout is a product of all these factors — its early role as a trading hub, the intervention of a fire, the allocation of farming real estate and the imposition of a modern grid.

Here and elsewhere, even the best-envisioned city plans are never fully realized without complications — few cities end up looking (or working) as any one urban planner intended.

Comments (2)

Share

If anyone is interested, there is an excellent blog that goes into a lot more detail about this:

http://detroiturbanism.blogspot.com

WRT: “In 1701, the French landed in what would eventually become known as Detroit.”

Le Détroit du Lac Erie was known on French maps in the 1600s, decades before any European settlements were created here. The French village and the city took its name from the water feature: the strait (le détroit).