Downtown Toronto has a dense core of tall, glassy buildings along the waterfront of Lake Ontario. Outside of that, lots short single family homes sprawl out in every direction. Residents looking for something in between an expensive house and a condo in a tall, generic tower struggle to find places to live. There just aren’t a lot of these mid-sized rental buildings in the city.

And it’s not just Toronto — a similar architectural void can be found in many other North American cities, like Los Angeles, Seattle, Boston and Vancouver. And this is a big concern for urban planners — so big, there’s a term for it. The “missing middle.” That moniker can be confusing, because it’s not directly about middle class housing — rather, it’s about a specific range of building sizes and typologies, including: duplexes, triplexes, courtyard buildings, multi-story apartment complexes, the list goes on. Buildings like these have an outsized effect on cities, and cities without enough of these kinds of buildings often suffer from their absence.

For starters, cities with lots of “middle housing” offer more rental options, and tend to be more affordable as well. Meanwhile, cities without middle housing tend to be harder for pretty much everyone except the wealthy — they also tend to be more segregated. So it’s easy to see why there’s some conflation between the “missing middle” and a lack of “middle income” housing options – because these two concepts are absolutely related.

When the Middle Went Missing

Toronto’s missing middle problem is pretty serious, and it can be traced back to early 20th century zoning laws. In the late 1800s, there was a big wave of immigration to North America, and most of these immigrants were moving to cities. In Toronto there was already an established population of British immigrants, but much of this new wave was eastern European. New multi-unit tenement buildings cropped up to house these new people.

But there was a backlash against these new immigrants, and in 1912, Toronto banned apartment buildings in most of the city. This ban was an early version of exclusionary zoning — the kind of residential zoning where large swathes of urban centers are reserved for single family homes, and only single family homes. Cities across North America were passing these kinds of zoning laws, and they were driven by a misguided perception that apartment buildings were dens of iniquity.

Developers at the time were trying to associate their buildings with European class and luxury, but were being met with accusations of facilitating immorality, fueled in part by racism. At the time, Canada’s elite were still largely

British. Toronto’s puritanical WASPs were scared these apparently filthy apartments would be too tempting for nice British families.

In reality, early apartment buildings were actually aimed at the city’s elite. The first two were built around the turn of the century and were so luxurious that they didn’t even bother including kitchens in every unit — residents were simply expected to order meals from the building’s restaurant. They were marketed to the rich.

But there were factions in Toronto that had a very different vision of its future, as a place filled with single-family homes. And while the debate went on, Toronto was growing rapidly. It went from 200,000 people at the turn of the century to half a million in 1920. With that, developers started buying up land to build apartments, but they faced fierce resistance from the city, including smear campaigns.

Some developers used fear around apartments for personal profit, like Alfred Hawes, who bought a lot, and threatened to build apartments in order to motivate others to buy it back from him simply so he wouldn’t follow through. When they did, though, he not only made a tidy profit, he also went across the street, bought another lot, and built an apartment building called Spadina Gardens.

Defiant Apartments

Spadina Gardens was only the fourth apartment building constructed in the city, and it received real pushback. The city didn’t grant Hawes a permit, and even rushed through a bylaw in an effort to stop his construction. But Hawes didn’t care. He built Spadina Gardens without a permit. He ignored the bylaw. And somehow, he got away with it.

Today, Hawes’ apartment building is still there and it’s now the oldest in-use apartment building in the city. It was marketed to elites, and to this day, it remains an expensive place to live — in part because those who want to live in this kind of place don’t have a lot of options.

Toronto could have had similar buildings across the city, and in cities like Chicago or Brooklyn, this building would not be particularly remarkable. But in 1912, Toronto instituted a ban on apartment buildings in most neighbourhoods called Bylaw 6061. This stopped developers from building all kinds of apartments, including expensive places for the city’s wealthy and fashionable residents, but also the kind of housing that’s affordable for middle class families.

Despite its success, Spadina Gardens didn’t kick off a trend of rogue developers defying the bylaws and putting up apartment buildings everywhere. Because after Bylaw 6061 was passed, city planners continued to be hostile to apartment buildings.

Doubling Down

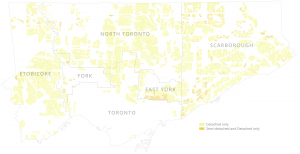

In the 60s the city of Toronto began to spread out and absorb surrounding municipalities. In these places, city planners designated many residential neighborhoods as “inviolate” meaning they couldn’t be touched by new development. The only new thing you can build there are single family homes. On the city land use map, these “inviolate” neighborhoods were colored in yellow. As result, Toronto evolved something called “the yellow belt,” a sea of neighborhoods where new development was limited to detached single family homes, which is more than twice the size of Manhattan.

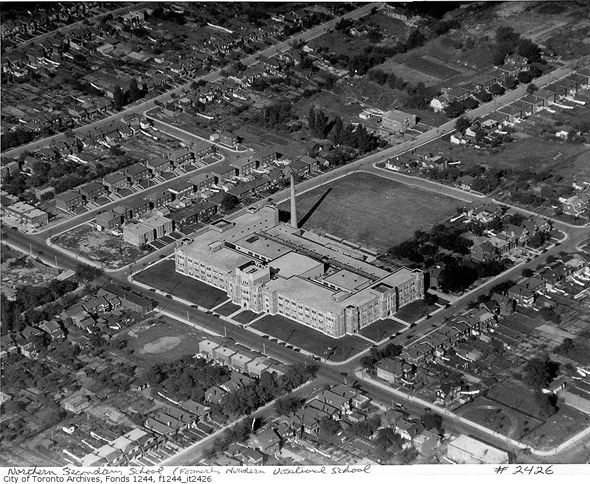

Urbanists say the lack of middle housing in Toronto has led to a divided city. If all you build are single family homes, that makes lots of residential neighborhoods unaffordable. Ironically, too, despite the fact that zoning was designed to “protect” single-family neighborhoods, it has led to problems in these theoretically utopian areas. Many of these neighborhoods are dropping in population, which in turn has consequences, like: local schools shutting down for lack of students.

If You Build It, Will They Come?!

Toronto has been building lots of giant condo towers in the last few years. In fact, between 1996 and 2016, Toronto built housing at roughly 1.5 times the pace of new residents coming to the city.

In theory, these condos should provide more housing, and bring prices down, but these new condos haven’t fixed the city’s housing woes. Toronto is still way behind in terms of housing availability, and the legacy of banning most buildings that would have made up the missing middle is partially to blame.

A report found that in 2020, Toronto had 360 housing units for every 1000 residents. That’s well below the average for cities in G7 countries, which is 471 units. And prices are high. A one bedroom apartment typically rents for over $2,000 a month, and that number keeps going up. These units aren’t putting downward pressure on the price of a detached house, which averages around $2,000,000.

The problem with condos is in part the hefty HOA fees, but also the fact that they serve a very limited demographic, mostly: young single professionals who want a clean, central, low-effort place to live, ideally close to where they work toward the city’s core.

Perverse Incentives

There are developers who want to build middle housing, but in most places it’s still illegal to build anything except single family homes. And in the places where you can put up taller buildings, all the incentives push you in the direction of giant condo towers.

Investors want to maximize returns, and in a place where permitting can take years, houses and high rises offer outsized returns — houses can be sold for a lot of money, and condo towers benefit from sheer scale.

On the condo side in particular: there are high fees and red tape, so once one goes through all of that, monetary incentives lead them toward ever-taller projects. If it takes the same amount of time to get a thousand unit building approved as it does a ten unit building, and the fees are high for both, there’s just little incentive to build smaller.

Thinking Outside the Zone

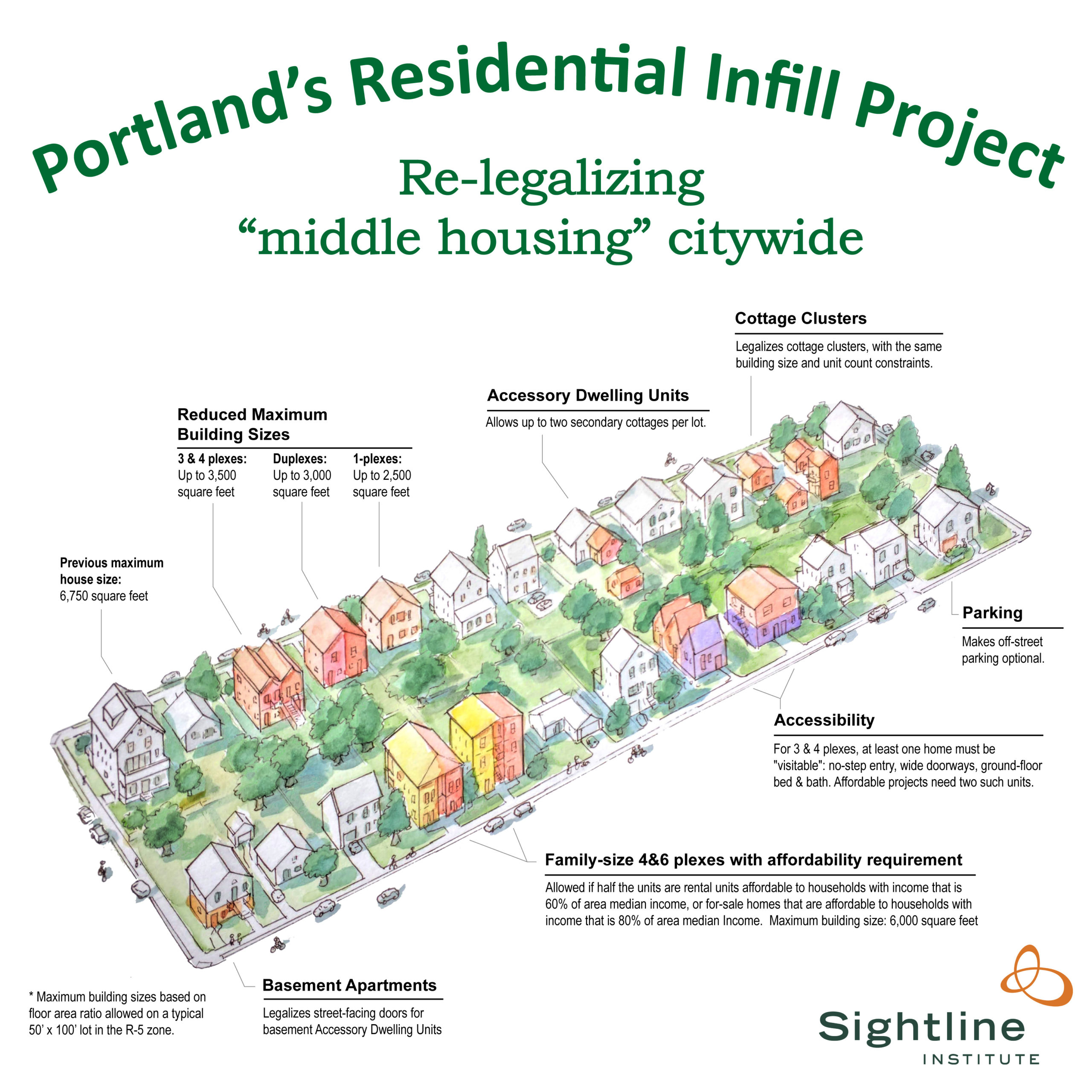

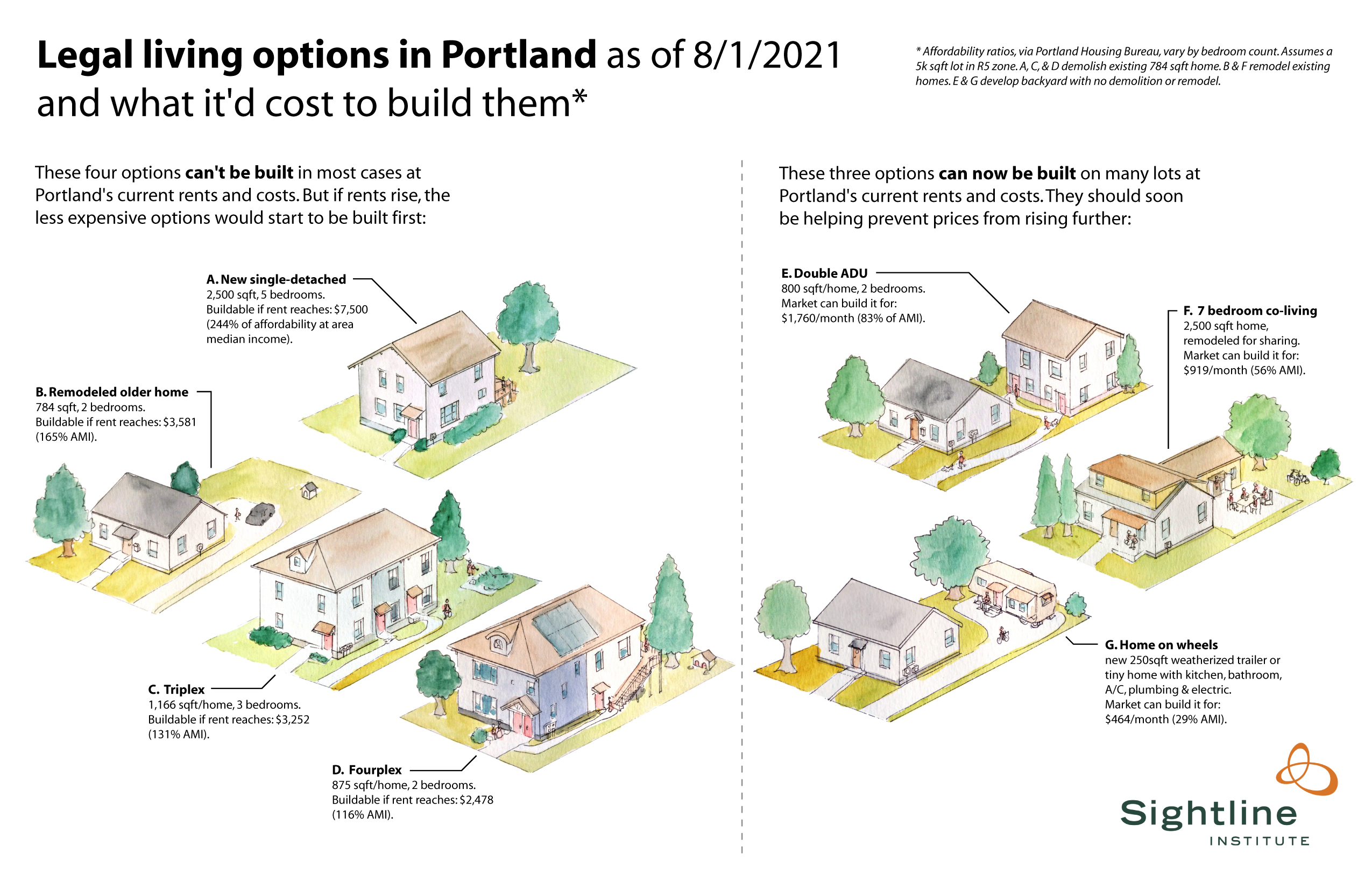

Toronto isn’t the only city with this missing middle problem. In fact, other cities with a missing middle have taken concrete steps to fix it, including Portland, Oregon, which has been working toward greater livability.

Portland eventually managed to ban single-family zoning, which is a significant step toward filling in that missing middle. It took a lot of work, and a lot of politics, but the bill passed in 2020, suddenly allowing things like cottage clusters and small apartment buildings almost everywhere. If someone wants to tear down an old relic of a house and turn it into a four-plex, that’s now possible. There are a lot of potential benefits, including: higher density and profits for developers.

But even with this new freedom to build, the situation on the ground has been slow to change. There are still profit calculations to be made and lines of red tape to be cut. Still, while zoning reform isn’t a silver bullet for a housing crisis, it’s a big first step. American cities like Minneapolis and Seattle have also recently banned exclusive single-family zoning to address this problem head on. But it will still take years of planning and development to create new apartments, and fill in that missing middle, but at least it’s a start.

Comments (1)

Share

This article is getting circulated amongst a few social media groups on urban life in Toronto, particularly as a response to the ongoing grief of NIMBYism that continues in full force here. But what it also does is spell out the consequences of a vacuum of intelligent critical writing on the urban environment and architecture generally here in Toronto.