Do you remember… airplane travel? Packing into a tin can with 200 other people all breathing each other’s air? These days most of us are still avoiding plane travel. But, in the Before Times, when we boarded a flight, we all received the same familiar set of instructions.

If you’ve ever flown on a plane, you’ve been directed to study the safety briefing card in your seatback pocket. Every passenger plane, commercial or private, has to have safety cards on board. Mo LaBorde is a reporter who has been collecting safety cards for almost ten years, and one day she started wondering how the modern safety card came about.

Fly the Skies! Don’t Think About Dying!

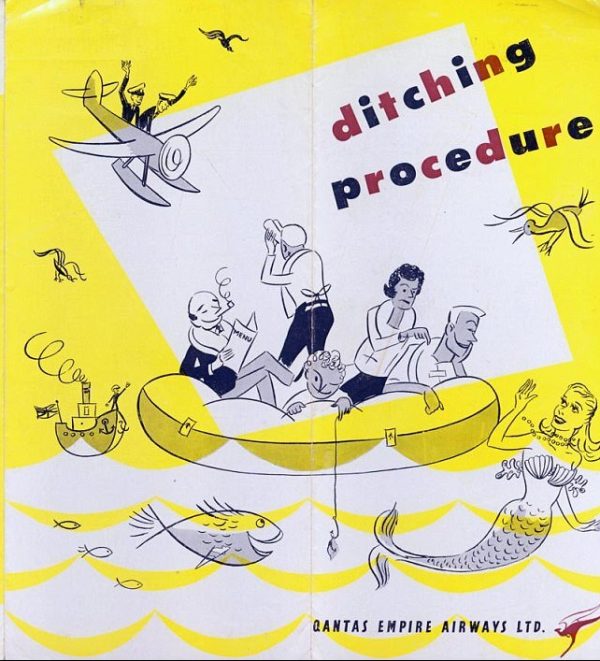

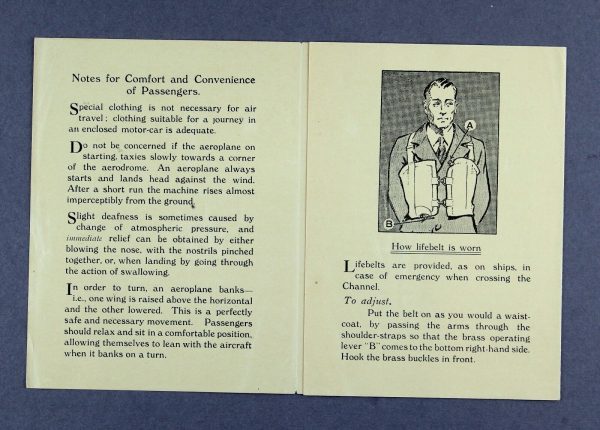

In the beginning, safety cards weren’t even really about safety. In the 1930s there was no regulation about what should go on the cards and airlines could put anything they wanted in them. This is because at the time airlines had to convince people to get on planes, so for many decades cards were all about soothing passengers and selling them on the idea that air travel was safe and glamorous.

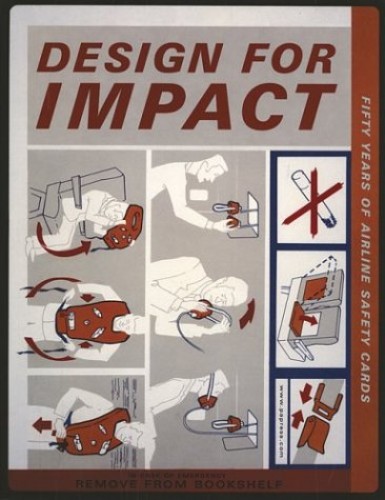

They were essentially miniature versions of those travel posters, like little advertisements for the airlines. The book Design For Impact by Johan Pihl and Eric Ericson, a compilation of historical safety cards, is filled with old cards like this one, many of which are incredibly stylish, but not much else. If you opened a card, you’d discover the instructions were usually hard-to-follow text.

By the mid-60s, carriers like Pan Am actually began begun to make a good faith effort into designing accurate cards. They created “fleet cards,” which were almost like a booklet that you would pick up, and it would have the safety and emergency instructions for multiple plane models in it, and each set of instructions would be in multiple languages. The problem was, no one wants to have to flip through an encyclopedic book in the middle of an emergency.

Things really started to change in the late 60s, when airlines started noticing a troubling pattern when it came to crashes. Psychologist and airplane safety expert Dan Johnson, explains, “Impact survival was possible, but not escape.” Johnson says that in the 60s the airlines knew that their airplanes were technically safer than ever before. They crashed less often and when they did crash, the crashes were increasingly less fatal. All of which should have added up to more survivors.” But what they realized was that survivors weren’t getting off the plane in time.

It turns out that both back then and today if you’re in a serious crash, it’s not the impact that kills you. It’s the smoke and the fire inside the cabin after the crash. So the key to surviving is getting out of the plane as fast as possible. Accident investigators found that, in your average crash, you had 90 seconds to get out of the plane before it became “unsurvivable.” But again and again, all through the 60s and even 70s, passengers weren’t making it out in time.

90 Seconds

In 1968 Douglas Aircraft decided to improve their safety record by hiring Johnson and another man named Beau Altman. Altman and Johnson decided to found a company together to improve the airline’s safety procedures. They called it the Interaction Research Corporation, and their specialty was running tests in mock plane cabins full of research participants. They would start by making each test as realistic a simulation as possible. They always made sure there were so many people under the age of six, so many people over the age of seventy and give them only as much information as they’d receive on a normal plane flight.

Then they’d toss a smoke bomb into the plane.

They would create a realistic simulation where the lights would go off and everyone would need to find their way to the exit, and when they did… the exit would be 15 feet off the ground and they would need to slide down an inflatable slide in the dark.

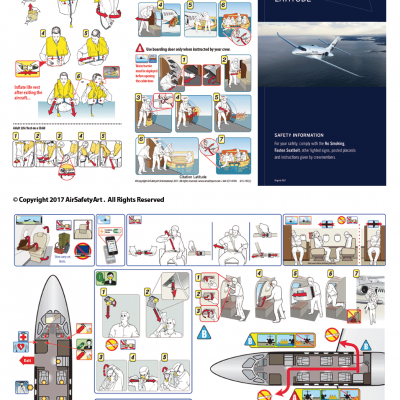

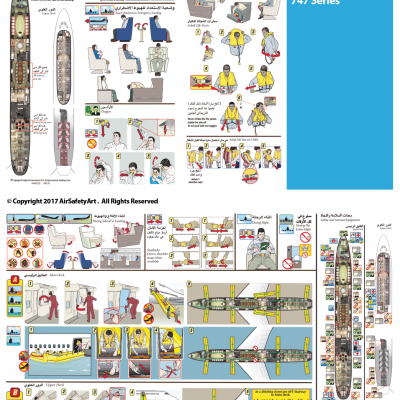

One of the most important things Beau and Dan learned was that one of the very best ways to get out of the airplane in time was to read the safety card. When they had people read the safety cards, and when those cards had the relevant information, the evacuation times improved dramatically. So they began applying what they learned in these experiments to the design of the cards. But since neither Altman nor Johnson were artists, they turned to Larry Bruns. Today, Larry Bruns and Brock Fisher are a grandfather and grandson safety card design team that runs Air Safety Art International, but back in the 60s, Bruns helped design the classic safety card look that we all recognize today.

They used pictures to tell the entire story of how to exit the plane. They zoomed in on specific actions like opening a door. And there were also things you might not necessarily consciously notice, but which really help, like using red for all exit related arrows and making sure the word “exit” is the only printed word in the sequence. The cards contained all these visual strategies that nudged the reader towards comprehension. And as a final design flourish, their cards even fit in the seatback pocket just right, so the title of the card peeks out and entices people to open it up.

Tenerife Test

Dan, Beau and Larry’s cards got put to the test in March 1977 on the island of Tenerife. Tenerife is in many ways the Titanic of travel. Since it involved two large planes, it’s still the single deadliest aviation accident in history. Why it happened is still up for debate, but what is known is that a 747 belonging to KLM collided on takeoff with a Pan Am 747 that was still on the ground and tore its roof off. On the KLM plane, everyone died, but on the Pan Am flight, 67 people survived, and it turned out Dan and Beau designed the safety cards on the plane with the survivors. Some of the survivors later explained that they knew how to get out of the plane thanks to the safety cards.

After Tenerife, Altman and Johnson actually testified before Congress about the need for better airline safety procedures, and it’s around then that all visual safety cards pretty much became standard throughout the industry. It also revealed that there are two large hurdles in airplane safety in disaster situations: that some people become so stressed out that they freeze, and that there are many people who don’t read the safety card in the first place.

Altman says the 96% of people who don’t look at the cards fall into one of two categories: Either they just completely resign their fate to the hands of the pilot when they board a plane, assuming they have zero control over the worst-case scenario. Or they have an optimism that’s made of steel. These are the people who never look at the pamphlet because they know how unlikely a crash actually is. The truth is we all need to actively participate in providing for our own safety.

Comments (17)

Share

What about the guy in the purple top hat and tux with tails!?

Such a high flying morsel of design history!

Safety manual inspired art series, please enjoy…

https://zilliams.com/images/art/22.jpg

https://zilliams.com/images/art/21.jpg

https://zilliams.com/images/art/23.jpg

https://zilliams.com/images/art/24.jpg

https://zilliams.com/images/art/25.jpg

https://zilliams.com/images/art/26.jpg

– ©Me :)

I love the live safety briefings by flight attendants.

Whether I was traveling regularly for business or on leisure flight, my attention is undivided and serious. Besides not wanting to be rude to the staff doing their jobs, watching puts me in a zen state. Not so much for the videos though.

And based on this episode, I eagerly await my next trip so I can start savoring the laminated safety cards.

I’ve been hoping that, with the ongoing events, less aircraft might be a continuing thing.

I guess I’m one of the small percentage of people who always read the safety card! I just always have. I suppose I feel if the info is out there to keep me safe, it’s my responsibility to know/review it to safe my own life.

Anyway, in the early 2000s sometime, I took a flight, and I wish I could remember which airline it was, but it had the best safety card ever! It literally featured a man in a purple tuxedo and top hat, and a full on ballerina in a tutu. Just wondering if Mo has that in her collection?

Great episode, as always!

According to Amazon, I bought my copy of Design For Impact on March 27, 2003. As much as I enjoy leafing through it, it’s one of my favorite spines to read. What better title for a design book can there be? What a striking pun!

Loved this episode, but I think you missed one of the craziest tactics for getting travelors to pay attention to the safety presentation — comedy. In the early days of Southwest, Spirit, and other budget airlines, real standup comics were hired as flight attendents, with the task of turning the safety spiel into a “laff riot.” Since comedy is by nature anarchic, it wasn’t long before this approach to the message was stretched too far, with jokes about clinging to spars in mid-ocean and so on. The comedy wasn’t the best, but it had a second-rate lounge lizard quality to it that could be appealing to the business travelor. Me, for example. I was one of those road warriors too cool to lift my gaze for the safety check. But when the jokes started coming, they had me at “hello.”

I was in USCG aviation as aircrew in helicopters and small jets.

We all went through dunker training where we learned that our amphibious HH3F helos are top heavy and even though they can float, if the rotor stops then it will flip over in anything but a calm sea.

We also learned that most people did not make it out when this happened because they could not find their way out. So the dunker is a mockup of a helo fuselage with seats, doors and windows. They blindfold you, strap you in and then drop it in a pool and turn it upside down.

You must take a breath while you can, wait for the plane to settle (upside down), release yourself, and make it out by yourself while keeping at least one hand ahold of something like a seat at all times (hand-over-hand).

Divers stand by. So when I get on a commercial aircraft I usually grab the safety card and identify at least the closest exit to me and count the seats to it so that I could get there in the dark.

I have been through a number of inflight incidents (fires, hoist cable through the rotor blades, etc.) and have gotten to experience passenger oxygen more than once. It feels like nothing and you just have to relax. This is something mentioned in briefings, but I doubt that people realize what it actuals feels like.

reminds me of Sully scene, Human Factor.. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N1fVL4AQEW8

I read safety cards and the final panel of https://photos.app.goo.gl/Szyr4j2r6MHRGoJN6 caught my attention – the person in the raft is cutting the line to the aircraft with a large knife! I carry one on board so rarely these days. The answer for to where to obtain it is in the caption.

Loved this episode. Normally…I’m a frequent flyer and this was familiar. But here’s a meme I love too lol https://scontent-dfw5-1.xx.fbcdn.net/v/t1.0-9/fr/cp0/e15/q65/126310589_3921992484479022_9014960997131975356_o.jpg?_nc_cat=1&ccb=2&_nc_sid=110474&efg=eyJpIjoidCJ9&_nc_ohc=KS1IzHiegAEAX9Pm6qX&_nc_ht=scontent-dfw5-1.xx&tp=14&oh=07b78986f4c56e76a103e2911a14287d&oe=5FDE3A48

I know this is selfish, but I have to wonder if I’m somehow related to Larry Bruns. That said, I’m very glad he and his family got the ball rolling on safety cards.

One of your best yet. Well done and thank you. (By the way, I’m also really enjoying the book.)

Loved this episode!

But as someone else above mentioned…. there’s other ways to get people to pay attention!

Here’s my favourite from Air New Zealand:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qOw44VFNk8Y

Oh, I thought you were going to link to this Air New Zealand safety video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7-Mq9HAE62Y (Look carefully at what they are wearing.)

Umm, you’re not supposed to take the card with you. How irresponsible, and also punishable. It says so right on the card.

Great episode

Now I can see that safety cards are designed incredibly well :)