About an hour northwest of Madrid, an enormous stone crucifix rises 500 feet out of a rocky mountaintop. It’s so big you can see it from miles away. Beneath the cross, there’s a sprawling Benedictine monastery and a basilica carved out of the mountain. This place is called the Valley of the Fallen. And it’s likely the most controversial monument in Spain.

The Valley is synonymous with Francisco Franco, the general who ruled Spain from the end of its bloody civil war in 1939 until his death in 1975. When Franco died, he became the Valley’s most notorious inhabitant. His body was buried under a huge stone slab.

As the decades passed after his death, anger about the monument grew. People began to push for the removal of Franco’s body. They argued there was no place in a democracy for a monument exalting a man who had tortured and killed thousands of Spaniards in the name of fascism.

And then in October 2019, Franco’s body was disinterred, his coffin packed into a helicopter, and then flown to a graveyard on the outskirts of the city to be reburied.

Despite the atrocities he committed, Franco still has supporters in Spain. Some even see him as the emblem of a traditional Spanish Catholic life, and some actually like his fascist ideology and would like to see it make a comeback. When his body was removed, hundreds of his supporters gathered at the new cemetery to wield swastikas and Franco-era flags, and to perform the fascist salute in his honor.

But this isn’t just the story of an old mausoleum and the dictator who used to be buried there. Because the monument is also a mass grave. There are tens of thousands of other bodies still trapped in the basilica beneath where Franco used to lie. Many were victims of Franco’s security forces, murdered during the height of the civil war. For years, their families have been trying to get them out.

El Caudillo

The story of the Valley of the Fallen can be traced all the way back to the mid-1930s when Spain found itself torn in two different political directions. The country was a new democracy in 1936 when a group of left-wing, anti-clerical republicans won the elections. This horrified the right-wing Catholics in the country, including Francisco Franco, a general in the Spanish Army.

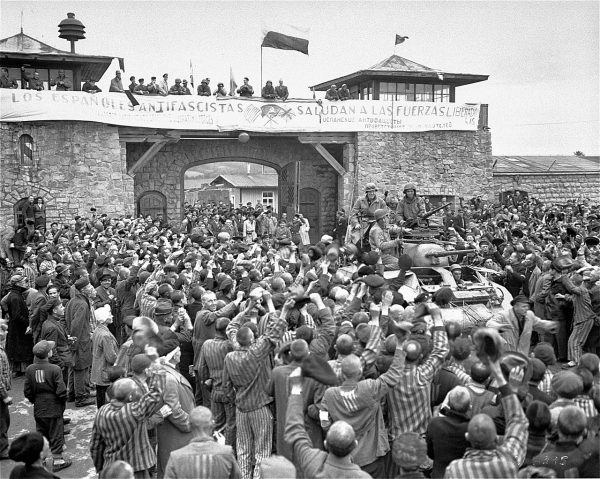

After the election, Franco banded together with other right-wing military leaders to carry out a coup. They believed they were on a divine crusade. In the resulting civil war, the right-wingers gradually seized control of Spain. Their death squads rounded up suspected leftists, paraded them through villages, and shot them.

Purificación Lapeña’s grandfather, Manuel, and great uncle, Antonio, were among Franco’s victims. Both men had supported the leftists who won the elections, and both had joined a union, making them targets for the right-wing nationalists. Manuel was working in the fields one day in July 1936 when a group of Franco’s men rolled up in a truck. They grabbed Purificacion’s grandfather and the other workers and took them to a nearby jail. Her grandfather was killed and left in a ditch, and her great uncle was murdered a few months later.

Over the years word spread through the village that the ravine where Manuel was killed was filling up with bodies, but it would take a long time for the family to find out exactly what had happened. They weren’t the only ones left without answers. Something similar was playing out for families across the country.

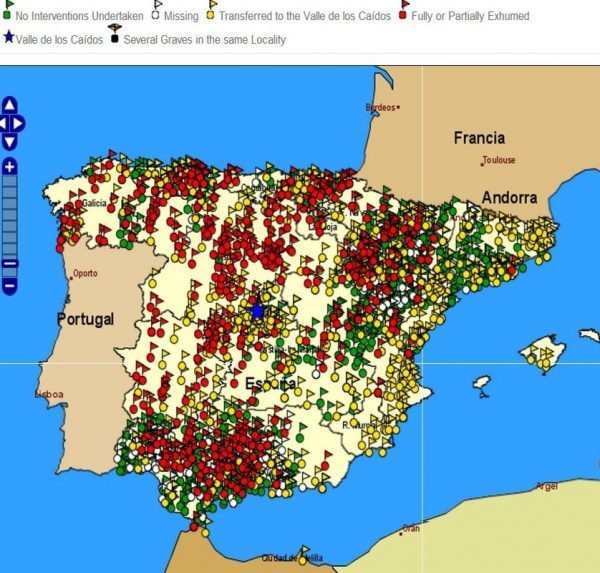

By 1939, the civil war was over, and Spain was in ruins. At least 400,000 people had died. Half of them were civilians who faced torture, assassination, and the unexplained disappearances of their family members. A network of mass graves now scarred the Spanish landscape. Some contained thousands of bodies.

The majority were victims of Franco’s security forces, like Purificacion’s family members. It’s estimated that Spain still has 114,000 missing people dating back to that time.

The Mass Grave Monument

Franco wasn’t interested in what happened to the bodies of his enemies, at least not at first. He was too busy consolidating his power. As the great superpowers of the world took sides in World War II, he decided not to fight, focusing his energies on fully crushing his opposition at home.

The country now had a single political party and protest was effectively banned. Franco became known as “El Caudillo,” the supreme leader. He was a Catholic authoritarian and under his rule, women lost rights they’d held in the 1930s, like the right to divorce, to have abortions, and to work outside the home without permission. Men, on the other hand, could kill their wives for adultery. The government banned regional languages, like Basque and Catalan. The Catholic Church ruled over every aspect of most Spaniards’ lives.

Once Franco had gained absolute power over the country, he wanted a monument to immortalize his great triumph. He commissioned the Valley of the Fallen in 1940. In a declaration, he proposed a site that would honor the achievements of “our crusade,” and the “heroic sacrifices of our victory.” The building, he said, would rival the grandeur of ancient monuments. And then, because he was Franco, he went about building the monument in the most fascist way possible, relying on the forced labor of his political prisoners.

The construction of the Valley of the Fallen took an enormous human toll. An estimated 40,000 prisoners worked on the project. Some died from exhaustion. Others inhaled pulverized granite and were killed by lung diseases many years later.

Franco hadn’t initially conceived of the Valley of the Fallen as a gravesite, much less a mass grave, but it would become one, thanks to Franco’s twisted response to pressure from one of Spain’s main allies: the United States.

The Americans relied on Spain as one of their European partners during the Cold War. And when they heard about Franco’s plans for the Valley of the Fallen, they started to get nervous. The monument was beginning to seem quite confrontational and divisive. The Americans hoped Franco would dial it back a bit, making it a place that memorialized not just the Catholic crusaders, but all the country’s war dead, sort of like Arlington National Cemetery.

And so Franco declared the Valley of the Fallen to be a place of reconciliation—a place where the dead from both sides of the civil war would be laid to rest. But then Franco made that happen in a way that would deeply alienate the people he had victimized.

He ordered his people to bring him bodies from mass graves and cemeteries all over Spain. Without permission, the bodies were dug up, jumbled together in boxes, and then relocated to the Valley, where they were reburied in the crypt near the basilica. Finally completed, the Valley opened to the public in 1959.

Generalissimo Francisco Franco is Still Dead

Nearly two decades later, when Franco finally died of heart failure, he too was buried at the Valley of the Fallen. He was laid to rest in a grand basilica near the bodies of the Spaniards he had tortured, killed, and then reburied in a mass grave where their families couldn’t find them.

The three years between Franco’s death and the signing of a new constitution became known as “The Transition”. The country moved from fascist dictatorship to multi-party democracy.

Starting in the late 1970s, Spain finally got to do what the U.S, Britain, and France had done more than a decade before—they got to have fun. A new revolutionary movement sprang up in Madrid and became known as La Movida Madrileña. Suddenly Spaniards could drink, dance, have sex outside of marriage, and make music about it.

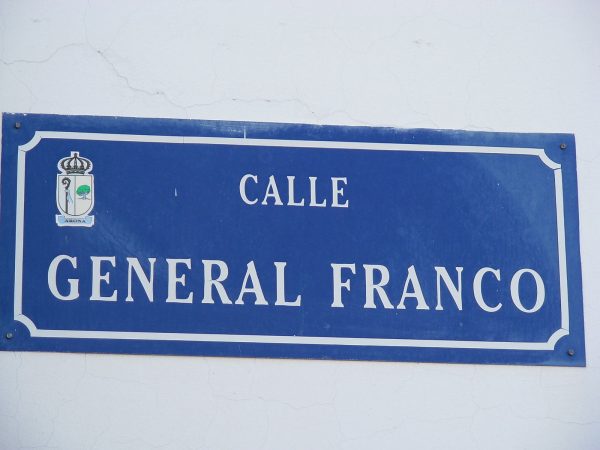

The Transition seemed to have ushered in a new Spain. But the elation felt after Franco’s death was temporary. For one thing, there were reminders of the dictatorship everywhere. There were statues of Franco and his collaborators in central plazas all over the country. His name was on street signs. And, of course, the Valley of the Fallen served as a colossal reminder.

But perhaps the biggest hurdle to fully addressing what had happened to the country under Franco was an agreement that became known as the Pacto del Olvido, the “Pact of Forgetting.”

At the heart of the Pact was legal forgiveness for all Franco-era crimes. It was a deal agreed to by parties on the right and the left. It was a massive compromise made in hopes of moving forward democratically. The left agreed to it because they wanted their political prisoners freed and their political parties legalized. They wanted to be able to live in this new democracy without fear of being tortured or murdered.

But as time went on, they had to grapple with the fact that the amnesty applied to people on the right too. Those who had tortured and killed civilians were shielded as well.

The Pact created a culture of silence around the atrocities of Spain’s past. It suppressed conversations about the killing of civilians during the civil war and the long years of repression that followed. The Pact basically said, “Let’s just not talk about what happened. Let’s move forward instead.”

Unforgotten

The Valley of the Fallen became something like a shrine to Franco, far removed from the Arlington-style vision he had promised. Fascists would visit from all over Europe to pay their respects and would mark his death with flowers every year. Franco was remembered, even as the Pact ensured his crimes were slowly forgotten and erased.

But for people like Purificación Lapeña, the Pact just didn’t work. It was impossible to move forward without knowing what had happened to her relatives. And as time went on, her family — and many others — began to resist the taboo against speaking up.

They also started to organize around an important goal. They wanted to find the bodies of their missing family members that had ended up in mass graves across the country. They began hiring forensic specialists and archeologists to help them find and dig up the bodies themselves.

In 2007, a new law went into effect that gave a boost to these efforts to uncover the crimes of the past. It was called the Historical Memory Law and it broke the Pact of Forgetting. For the first time, victims of Franco-era crimes received official recognition. The law called for the removal of Francoist symbols from public places. And lots of new money flowed to the exhumation efforts happening at mass grave sites across the country.

Purificación Lapeña and her family seized their chance. They hired a lawyer to help them investigate what had happened to their family members, and he discovered they were not in a mass grave near the town where they’d been killed. Instead, they were among the bodies that had been moved to the Valley of the Fallen in 1959. All told, around 33,000 bodies had been reburied at the monument.

Purificación eventually banded together with more than thirty families. They filed a series of legal complaints that wound their way through regional, national, and European courts over the course of many years.

In 2011, the government asked a panel of experts to consider the future of the Valley of the Fallen. The panel recommended that Franco’s body be removed from the Valley, a small victory for those who’d long said the Valley was a monument to fascism. With Franco’s body moved to another cemetery, at least the fascist pilgrimages would stop.

But the panel also said that identifying and removing the tens of thousands of other bodies was not practical. Of all those buried in the Valley, twenty-one thousand could be identified. The other twelve thousand people remain nameless. The only thing known is where their bodies came from in Spain, offering a small sliver of hope for families still searching for their loved ones.

Not Gone, but Forgotten

The efforts to address Spain’s fascist past remain patchwork — not just at The Valley of the Fallen, but across the country. There are still Franco-era statues and street signs. And recently, more insidious reminders of the dictatorship are re-emerging in the country today.

A new far-right party, known as VOX, won seats in parliament last year. They would never claim to be fascist, but their policies align with what Franco represented. VOX puts on events that attract many young people who have never voted before. And many of them don’t even know who Franco is. In a lot of ways, the Pact of Forgetting actually worked. Recent history isn’t taught in Spanish schools, which means young people are more susceptible to VOX’s appeal. They don’t understand the party’s connection to Spain’s bloody history.

The opinion is now divided on what the future of the Valley should be. Some want the government to stop maintaining it and to just let the monument fall down.

Purificación Lapeña says the most important thing is to get the rest of the bodies out of the Valley, not just Franco’s. She wants all families to be offered the chance to rebury their loved ones and for the real history of what happened during Franco’s regime to be taught in schools across the country.

In 2016, a judge ordered an exhumation of Purificación’s family members, but it still hasn’t been carried out. And while they are not getting their hopes up, it’s true that in Spain, the dead have a way of surprising the living.

Comments (4)

Share

My mom is a refugee from fascist Spain. She came to Mexico with her mother when she was five years old. Here, they reunited with my grandfather, who had been an air force captain for the Spanish Republic and had had to flee on foot through the mountains to France, after which he made it to Mexico. As kids, my siblings and I rarely heard about Franco or about the concentration camp where my grandfather had been a prisoner in France. In 1980 my parents traveled to Spain to visit with my mother’s family. For some reason, they visited the Valle de los Caídos. My dad discreetly pulled away from the group, rounded a corner, and peed on the monument! It was his little revenge for what Franco had done to his wife’s family. The day my dad peed on Franco’s grave became legendary in our family’s narrative.

I remember visiting Spain as a child. It was 1983; I would have been about eight years old. I had seen a large slogan spray-painted on a promenade wall in Blanes, on the Costa Blanca. It was something about “el mort Franco.”

Well, when your eight years old you assume that Dad knows everything. I asked him what it meant, and who was Franco. He showed me an old 25ptas coin. On it was the head of an old man, (like the Queens head would have be on a British Coin.) He said “That’s him. Now don’t ever mention that name here again. Some people will spit on you. Others will smash your face in for just saying his name.” I didn’t mention that name again until we got back to the UK.

I rarely come across articles so poorly documented and with such a partisan tone.. Many have criticized Franco and many have defended him too.. All is good as long as serious research and unbiased sources are used. Not here.. Not today.. The author so eagerly inclined to count the thousands killed by Franco fails miserably to count the thousands killed by Republicans.. Not to mention the failure of the republic to protect religious freedom in a mostly Catholic country..by the way two years before the conflict started.. Burning churches was their thing and killing priests and nouns too.. That is why the infuriated conservatives reacted..to those who fled fearing for their life its sad they missed the Amnesty granted by Franco.. Which by the way the author also forget..

The civil war was a grab for power by fascists that hid behind the perceived moral superiority of the catholic church, even though the Nationalists killed priests too, just for supporting the Republic. Franco had no problem working with Nazi Germany and Mussolini to win the war, leading him to kill more people than the Republicans ever could. There is no defending him.

Franco was a horrible, repulsive, inhumane dictator who is responsible for immeasurable suffering and countless deaths, with the full support of the catholic churc,h yet here you are, regurgitating his fascist talking points.