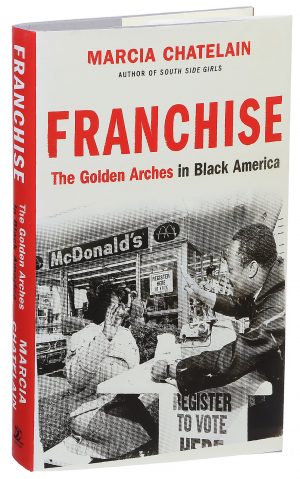

There are many books about McDonald’s that criticize the company for its many sins, and author Marcia Chatelain has read all of them. But her book comes at this famous fast-food restaurant from a different angle and with a much wider lens. In Franchise: The Golden Arches in Black America, Chatelain offers a critique of racial capitalism and a long history of trying to address social problems with business-based solutions.

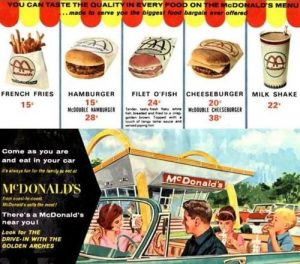

Today, fast food is ubiquitous and easy to take for granted, but for Black people in the 1970s, it was life-changing. With new federal protection in places like restaurants (albeit not always enforced), McDonald’s became a big deal. For those in the South during the Jim Crow era, it was often a struggle to find a restaurant where they would be served. National chains like McDonald’s became some of the first desegregated restaurants in the area.

Today, fast food is ubiquitous and easy to take for granted, but for Black people in the 1970s, it was life-changing. With new federal protection in places like restaurants (albeit not always enforced), McDonald’s became a big deal. For those in the South during the Jim Crow era, it was often a struggle to find a restaurant where they would be served. National chains like McDonald’s became some of the first desegregated restaurants in the area.

As fast-food restaurants spread, so did the Civil Rights movement. Amidst growing unrest in the late 1960s, many white owners with franchises in predominately Black neighborhoods wanted out, and when they left, Black franchise owners often stepped in to fill the void. In an era of “white flight,” people moving to the suburbs left not only their homes behind but in many cases their businesses as well, paving the way for new management.

After 1968, many national companies began to see opportunities in Black capitalism, a doctrine that said the problems facing Black communities could be solved by major investments in local Black businesses. Suddenly, McDonald’s was at the forefront of giving inner-city franchises to Black businessmen and capitalizing on federal programs that were designed to support Black business ownership.

After 1968, many national companies began to see opportunities in Black capitalism, a doctrine that said the problems facing Black communities could be solved by major investments in local Black businesses. Suddenly, McDonald’s was at the forefront of giving inner-city franchises to Black businessmen and capitalizing on federal programs that were designed to support Black business ownership.

Franchising, as Chatelain describes it, “is the idea that a parent company makes all the rules but the children earn all the money.” The franchise model is very American, she argues, because it doesn’t require advanced education or even a lot of business savvy. It is a space of opportunity, at least as long as one plays by the rules — a way for anyone to (at least in theory) become an entrepreneur.

Black franchisees became well-known figures in the neighborhoods where they operated stores, and those stores became multi-functional spaces — places to hang out, but also institutions underwriting local sports teams and offering services like voter registration drives.

Chatelain argues that Black capitalism of the 1970s was a success at convincing people that entrepreneurship was the best way to revitalize neighborhoods. At the same time, she views this as a failure of government — Black business owners were often forced to fill in voids left by the state, with their restaurants becoming a de facto daycare center and job training program in many neighborhoods.

McDonald’s effort to recruit Black franchisees was not without controversies. Over the decades, McDonald’s and other large chains were accused of discriminating against Black franchise owners seeking to open locations in mostly white neighborhoods. One high-profile case in Los Angeles ended up spurring selective boycotts of white-owned McDonald’s locations. The NAACP got involved, entering negotiations with McDonald’s — a precedent that would be repeated in other places and with other large businesses in and beyond the 1980s. Many corporations came to the table offering charitable donations and other support for Black Americans, which framed the larger question of racial inequality in a strangely narrow corporate context — there was a notion that economic opportunity could help create social justice.

As McDonald’s expanded and Black patronage and ownership grew, the company started developing targeted advertising, some of which can seem a bit cringe-worthy in hindsight. One series of vintage ads centers around a young man named Calvin, framing the character as someone whose life was improved by working at McDonald’s. In later ads, things come full circle, and Calvin (once an entry-level employee) muses about becoming a franchise owner himself.

There is a lot of nuance in Chatelain’s perspective on these kinds of targeted campaigns. In them, there is some obviously crass commercialism; but McDonald’s really did create economic opportunities, too, hiring Black creatives to work on advertisements and encouraging Black youth to seek employment at these franchises.

The company was also an early advocate for Martin Luther King Jr. Day in the early 1980s as a federal holiday, at a time when perspectives on him as a figure were still polarized. In a way, this was a full-circle move for the corporation, too — King’s assassination had been a factor in their shift toward embracing Black customers and franchisees, and this embrace of MLK’s legacy, considered risky by some, made sense.

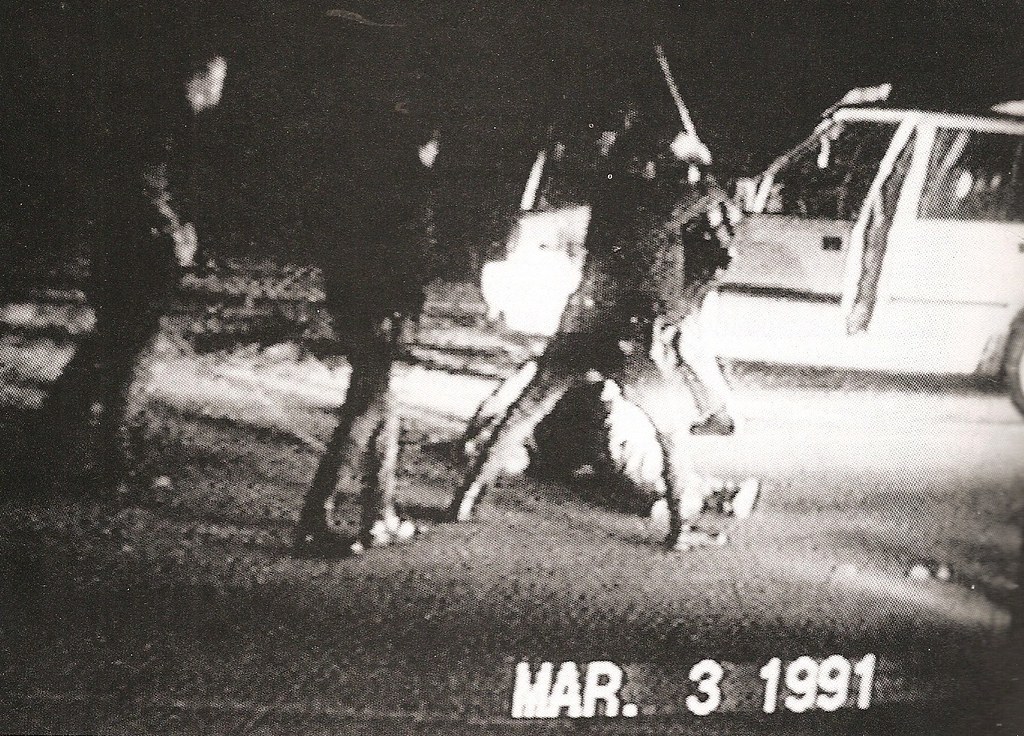

Following the acquittal of police officers involved in the brutal beating of Rodney King in 1992, the CEO of McDonald’s made a bold claim that the company’s LA-area franchises were spared during the riots because of their long alignment with Black Americans. Chatelain is skeptical of the claim, but acknowledges that McDonald’s corporate was essentially successful in positioning the company as being aligned with Black people. So while the sound bite may not have been fully accurate, it reflected a certain internalized reality.

Chatelain sees the current reality of franchises in nuanced ways. On the one hand, Black business owners have been empowered to make money as well as positive impacts in their communities. On the other hand, franchises are still beholden to larger corporate overseers with their own interests and bottom lines. So while franchises have provided real opportunities in various ways, they also have reinforced many systemic problems over the decades as well. In the end, Chatelain says she’s “come to a place of understanding that fast food can be harmful and it can be deeply meaningful.” For more, be sure to check out Franchise: The Golden Arches in Black America.

The coda was produced by Phoebe Ünter and taken from episode 3 of The Heart in a series called Race Traitor (2020). Even after you’ve intellectually rejected white supremacy, how does it show up in a room? In a relationship? How do we divert intergenerational white power hoarding that is so normalized it’s nearly invisible? Phoebe’s been white her entire life. But she only realized a few years ago that she inherited a white value system. Through conversations with friends and confrontations with family, she takes inventory of the ways she embodies white supremacy — in order to disrupt it.

Comments (6)

Share

Chatelain argues that Black capitalism of the 1970s was at success. I believe you mean a success. Great episode though!

In Copenhagen Denmark, we have a sociolance. That is a vehicle with personal specialiced in taking care of cases that nead social/psykological and health advice especialy for socially exposed people.

Your podcast has turned into all race all the time. It’s no longer about design, so maybe you should change your description on iTunes. Anyway, I’m out. (And cue the shrieking in comment responses calling me a racist for coming to a design podcast hoping to learn about design.)

bye

Anyone who can’t see design in this discussion is probably too blinded by, well, something, to see that design is found throughout this story (how ads are made, how McDonald’s organized its franchise structure to capitalize on black neighborhoods, etc.).

I liked this episode but when I heard the the expert say she was amazed at how much skill is involved at making fast food fast I had to stop and question everything she’d said. I worked in fast food for Hardee’s and McDonalds as a teen and there is no skill involved. They actively remove skill requirements to standardize tasks, and the fact that adult workers that aren’t managers are no more trustworthy than the 16 year olds.

In fact when I was a college student and was hired at a real restaurant as a preparer and appetizer cook when they heard I’d worked 2 years in fast food they replied I had no experience and was put on dishes.