Maybe you have a story like this. How once upon a time, on the outskirts of the town where you grew up, or where you went to school, on the edge of the woods, there was a scary old asylum. But the one detail that almost never varies, the thing that seems to make an asylum story an asylum story, is that the asylum is nearly always… abandoned.

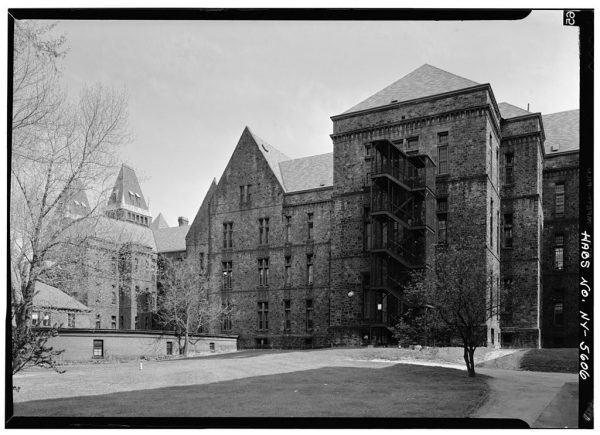

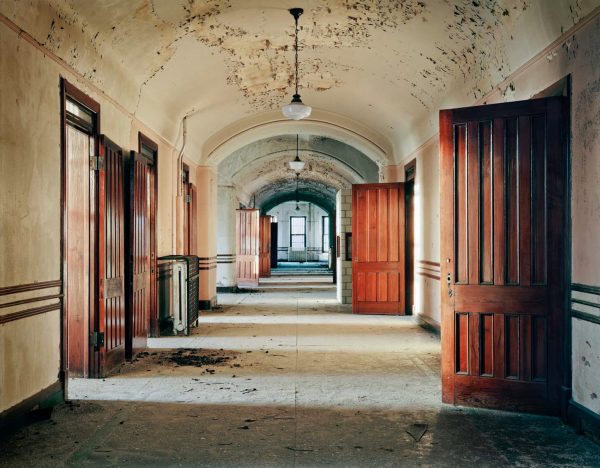

Corey Fabian-Barrett is a historian who works at an old decommissioned asylum on the north side of Buffalo, New York. Today it’s called the Richardson-Olmsted Campus, but its original name was Buffalo State Asylum For The Insane. From the outside, the building is everything you’d expect of an abandoned asylum: an imposing stone edifice, its windows boarded over, surrounded by a chain-link fence. But even though the building is falling apart, it is clear that back in the day it hadn’t just been imposing but fancy. The exterior, for example, is Medina Sandstone — just like Buckingham Palace.

Today, there are more than a hundred abandoned asylums in the United States, many of them not all that different from Buffalo State. It’s one of the reasons we’re all so familiar with the idea of the big empty asylum in the woods. Few stop to wonder where all these structures came from, but, in fact, all of this was part of a treatment regimen developed by a singular Philadelphia doctor, a physician who was obsessed with architecture and how it could be harnessed therapeutically to cure those who’d become insane.

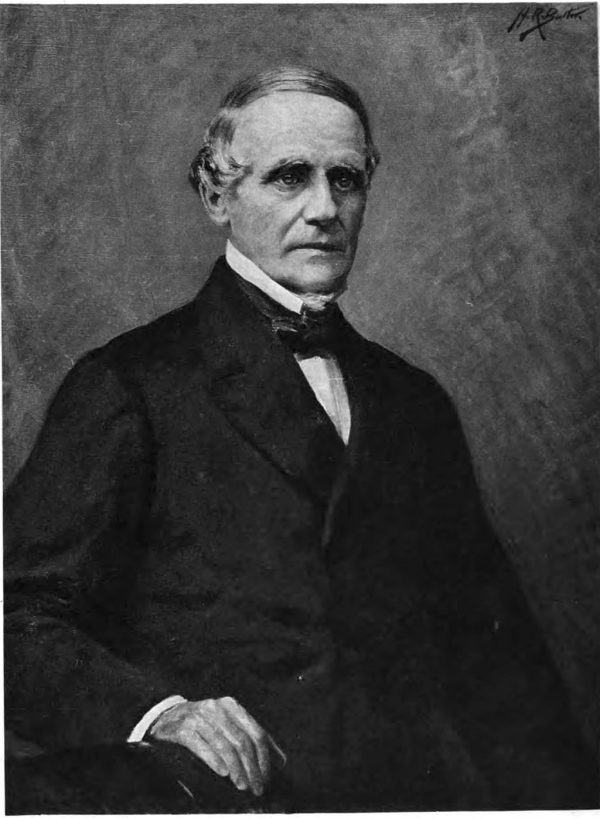

Thomas Story Kirkbride

“[Kirkbride] was one of the first people in America to say there’s something better we could be doing for people with mental illness,” says Corey Fabian-Barrett. “He was one of the first people to recognize mental illness was something that could potentially be treated and cured, that it wasn’t just a condition where you would lock somebody up in the basement and throw away the key.” Thomas Kirkbride was a Quaker, born in the Pennsylvania countryside in 1809. His father was a farmer, but young Kirkbride discovered early on he wasn’t suited to farming and decided to become a doctor. At first, he wanted to be a surgeon, but he somehow got talked into working instead at a Quaker-run insane asylum outside Philadelphia.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, when someone was deemed insane, it was often thought to be the person’s own fault. “The assumption was they were […] forsaken by God or they were possessed by demons or they had done something to deserve to be in such a desperate condition,” says Carla Yanni, an architectural historian at Rutgers and author of the book The Architecture of Madness: Insane Asylums in the United States. She says that what happened to someone labeled insane in the early 19th century would have depended mostly on their class. Wealthy families often kept insane relatives at home or paid for them to live in private madhouses. Poorer people fared worse. They were cast out alone, and a lot of them ended up in jails or hospices.

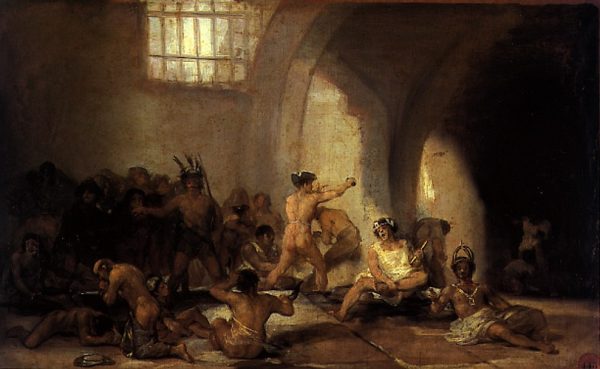

Madhouses in that era were more like prisons. They focused on confining and often torturing people. Some even offered the opportunity to let outsiders come and gawk at the patients kept inside. But the Quaker asylum that Thomas Kirkbride had visited was very different. It had a newer, gentler philosophy of how to treat patients called “moral treatment.”

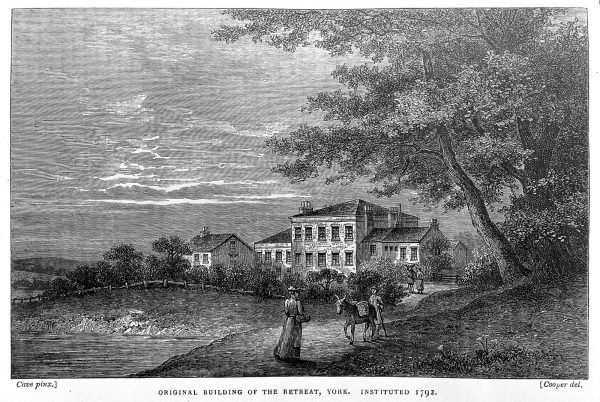

Moral Treatment

Pioneered by a small handful of asylums in Europe, moral treatment was part of a growing trend among professional physicians who believed that patients didn’t have to be confined indefinitely. Instead, they could be treated — even cured. That meant the person should get enough rest, should sleep on a regular schedule, should eat healthy food, should go for walks and get exercise, and should go out and experience nature.

Kirkbride worked a few years at the Friends Asylum, learning and practicing moral treatment. Then in 1840, he became superintendent of his own asylum, the Philadelphia Hospital for the Insane. It was here that he began thinking about another way to treat insanity. He started thinking a lot about the environment where patients were treated.

As part of a push to get patients out of that prison-like basement, the hospital had already commissioned a brighter, more spacious building in the countryside, but Kirkbride came to believe that even this wasn’t enough. He wanted an asylum designed with treatment in mind. A few years later, Kirkbride was given the opportunity to construct his own facility for the hospital and began to experiment. The architecture of the building, the landscaping of its grounds, the efficiency of its operation — nothing was left to chance. He documented everything he learned in an extremely detailed book called On the Construction, Organization, and General Arrangements of Hospitals for the Insane With Some Remarks on Insanity and Its Treatment.

The How-To Guide for Asylums

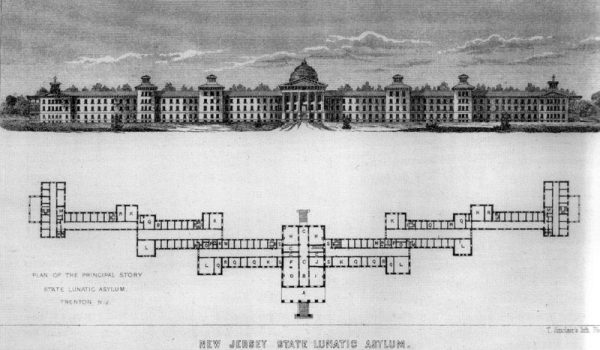

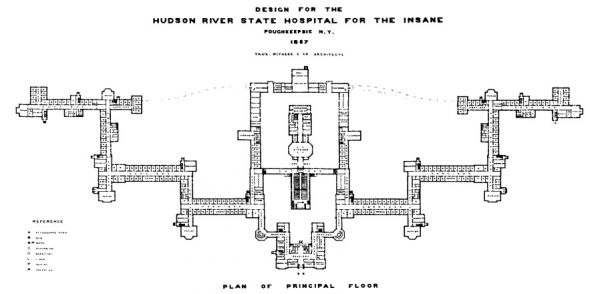

Dr. Kirkbride’s book is highly specific, even recommending particular building materials and colors of paint, strategies for how to avoid vermin and other sources of potentially bad odors, and descriptions of the ideal character and demeanor of the staff. But the most striking aspect of Kirkbride’s plans for this asylum/hospital of the future wasn’t the windows or the fences or the plumbing. It was the building’s shape. It was built in a V-formation, almost like a flock of birds.

The V consisted of two diverging series of wards or “pavilions.” New arrivals would arrive at the administrative offices at the center of the V. From there, patients would be segregated by gender, men going to one side, women to the other. They would then be further segregated by condition, according to four distinct levels of need. Patients requiring the most care would be kept in the pavilions furthest from the center, which meant that as you improve, you’d literally move toward the exit.

Since each of the pavilions would be set back slightly from the last, every room in the hospital would receive maximum ventilation and sunlight throughout the day. The narrowed points of contact between sections also protected against fire, by making it easier to seal off any one part of the facility from the others.

Nature itself was thought to be curative, and Kirkbride called for the asylum to be surrounded by parkland, so that as you walked down a building’s tiered corridors, with its tall ceilings, in almost every direction you turned, you would see towering landscapes of greenery and sky.

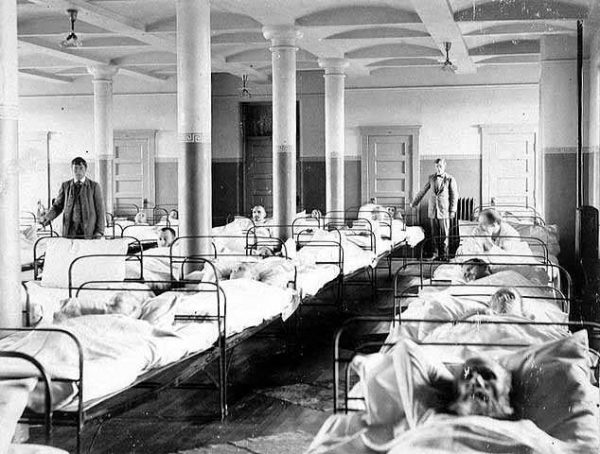

The idea was to make an asylum feel like a Victorian home. “Each ward was supposed to be structured like an ideal Victorian family unit,” says Fabian-Barrett, “So they all do everything together. The doctor has meals with them at the head of the table to model an ideal of Victorian fatherhood. The nurse, the matron, at the other end of the table is the mother, and they’re all acting like this family.”

Moral Reform

At the same time Kirkbride was writing his book, a whole moral reform movement was building around the idea that society had a duty to provide care for the less fortunate, much like a father should provide for his children. The most famous of the reformers was a teacher from Massachusetts named Dorothea Dix.

Dix toured the country, counting and writing reports on the condition of what she called the “insane poor.” Barred as a woman from speaking to state legislatures, she’d write powerful speeches that she would then have men deliver on her behalf. One by one, she got 20 states to fund public asylums. Dix even got a bill passed by Congress that would have provided ten million acres of federal land for their construction, but it was vetoed by President Franklin Pierce in 1854, the same year Kirkbride published his book.

Kirkbride and Dix corresponded frequently. He even included a reminder in his book specifically addressed to officials who opposed state spending on asylums: that anyone, including them, could go insane. It didn’t matter their race or creed or class. Kirkbride called insanity “the great leveler.”

When On the Construction, Organization, and General Arrangements of Hospitals for the Insane With Some Remarks on Insanity and Its Treatment was released, it was an instant hit. Hospitals started popping up all across the country. In 1840, the United States had just 18 asylums. By 1880 there were 139, most of them built with state funds according to the Kirkbride Plan. The Plan gave an architect everything he’d need to build a beautiful, optimally functional asylum. With their distinctive V-shape, they were soon known simply as “Kirkbrides.”

And as large as these buildings were, the grounds around them were even larger. Many Kirkbrides contained working farms — with vegetable gardens, greenhouses, dairies, livestock, and bakeries. Kirkbride believed that patients being occupied was key to their recovery. Patients therefore aided in farm work, and other tasks regarding the daily operation of the asylum, often according to their previous occupation. Doing work was part of moral treatment, but so was amusement. Kirkbrides had ballrooms, bowling alleys, and baseball diamonds. One even had a pre-electricity roller-coaster.

Past Capacity

By the late 1850s, asylums had become symbols of both a belief in insanity’s possible cure, but also civic and social achievement. Any self-respecting American town desperately wanted its own asylum. It was a source of jobs and pride. Postcards would frequently feature a lovely drawing of the area’s Kirkbride.

In 1865, the New York legislature agreed to fund a new asylum to serve the western half of the state. The building was designed by H.H. Richardson, the father of American architecture, and the grounds were designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, the designer of Central Park. Olmsted expertly positioned the Kirkbride, picking a spot and orientation that maximized sunlight, and then surrounded it with hundreds of acres of landscaped “pleasure grounds” planted with imported trees.

But from its inception, there was a gap between the architects’ ambitions for the building, and how the building actually functioned. For one thing, the very size of the Buffalo asylum — as with many other state asylums that followed — ended up working against it. Kirkbride was adamant a superintendent should be able to visit each and every patient so that an asylum should be 250 patients maximum. During the 1866 annual meeting of asylum superintendents, members – under financial pressure to take in more paying patients — wanted to increase the maximum asylum size to 600. Kirkbride voted against the measure, but it passed anyway.

When H.H. Richardson designed the Buffalo Hospital for the Insane in the early 1870s, he designed it for the maximum of 600 patients. It ended up being so large that construction took twenty years. And after its completion, the size continued being a problem. There were never enough attendants or nurses, which ruined several aspects of the moral treatment. But the larger problem was that many patients staying at Kirkbrides didn’t leave. From the beginning, the idea had been that the patients in any one Kirkbride hospital would soon be cured, continually making room for new patients. Patients were originally expected to stay there for no more than a year.

Kirkbride himself claimed that his asylum in Philadelphia had an 80% cure rate. Others superintendents claimed rates as high as 90 or even 100%. But the doctors had been collecting and reporting their own data, so a person who died in an asylum might be counted as cured, while a patient who required a second visit might be counted as two people cured. The net result was that once a Kirkbride asylum opened, it quickly filled up and stayed that way. They ended up becoming places that poor and sick people spent their entire lives in. Wealthy patients, whose payments had helped maintain these ornate facilities, fled to private hospitals, leaving Kirkbrides like the one in Buffalo to fall into disrepair.

The Downfall of the Kirkbride Plan

By the mid 20th century, the buildings had become overcrowded. Buffalo’s asylum, which was was designed for 600 was treating 3,600 patients in house. The state mental hospitals constructed during the early 20th century grew even larger, resembling institutional buildings, even prisons, the very thing Kirkbride had wanted to avoid. The largest, Pilgrim State Hospital on Long Island, at one point housed over 14,000 patients. By 1955, over half a million Americans were confined in state mental hospitals.

Meanwhile, psychiatrists had turned their focus to curing what were now termed mental illnesses. They focused on physical interventions like lobotomies, insulin comas, electroshock treatments, and eventually chemicals marketed as psychiatric drugs.

In the 1960s, new laws prohibited psychiatric patients from working. Without the contribution of patient labor, many hospitals’ infrastructures were brought to a halt. Then starting in the 1970s, American state mental hospitals were largely defunded, emptied and shuttered during what was called “deinstitutionalization.” The Kirkbride in Buffalo was finally shut down, and its few remaining patients were transferred to a smaller, more modern facility across the street in 1974.

Almost everything about the original purpose of these buildings, and others like them, had been forgotten. Asylums were reduced to the role of a pop culture trope, one built entirely out of their last, gruesome chapter. Take Batman’s Arkham Asylum, sitting just outside Gotham, alone on a hill, with its grand Gothic architecture, or the terrifying institutional nightmare of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

The Opposite of Creepy

is a photographer who’s probably been inside more Kirkbrides than anybody else. He photographed 70 abandoned asylums in 30 states for a book called Asylum: Inside the Closed World of State Mental Hospitals. Payne often gets asked if being inside these Kirkbrides felt “creepy,” but he doesn’t see them that way. “I didn’t find them creepy, ” he says. “At the very opposite I felt lucky to be in them and to be able to photograph them.”

Payne spent hours photographing his first Kirkbride, and what he found is that, despite decades of disrepair, these buildings could still impress. The light still flooded in through the 16-foot windows. The trees planted 130 years ago had grown tall and graceful. Much of Kirkbride’s original vision remained intact. “I think that you know when you go to architecture school every architect dreams that their design or their building is going to sway someone, you know? Move someone on that level, change their lifestyle, change their mind,” he explains. The power these buildings once had is part of what Christopher wanted to capture.

A New Legacy

Of the few dozen Kirkbride Buildings that are still standing, many are in the process of slowly decaying. They’re regarded as public nuisances or expensive headaches. A handful have managed to stay open, though often in a very diminished capacity — a small portion of the building used for some administration function while the rest is abandoned.

Some Kirkbrides have been or are being transformed into condos. Another one in Sydney, Australia, became home to an art school. A Kirkbride in Washington, D.C. is about to become the headquarters for Homeland Security. The Kirkbride in Buffalo is not entirely abandoned either. Part of it is now a luxury hotel. Corey Fabian-Barrett says it’s an especially popular spot to get married, sometimes because the couple is interested in the history of the asylum. Although, sometimes, they just want a place that looks like Hogwarts.

This story was produced and reported by writer Sandy Allen. Their book about the history of mental health in America, A Kind of Mirraculas Paradise: A True Story about Schizophrenia, was published by Scribner and is now out in paperback. They’re also the host of the show Mad Chat, a podcast which unpacks what our pop culture is telling us about madness and mental health.

Comments (8)

Share

Sorry that my comment doesn’t concern the topic of the episode; I promise you I did find it very interesting.

I was bummed out when shazam didnt recognise the snippets of music and couldn’t direct me to a whole album worth of those sounds. Particularly the snippet at 25: 50 is just lovely. It’s a rainy afternoon and I’m doing the washing up and I want that music playing in the background but 20 seconds just isn’t enough time to get the chore done and I my fingers are wet which makes looping back constantly a tad impractical. Please urge Sean Real to consider expanding their 99 pi work into an album. Thanks.

I LOVE your show, I’ve learned so many things I didn’t know I didn’t know :) I’m a little disappointed that you didn’t mention occupational therapy when you were discussing Gould Farm in episode 373. The belief that meaningful work is essential to mental (and physical) wellness is the basis of my profession. I happen to work in an industrial setting however I have many friends and colleagues who exclusively treat people with mental illnesses of all severities and varieties in a wide range of settings from inpatient or residential forensic facilities to community based services. Gould Farm sounds like it is an amazing place to live and work. I hope that more services and facilities harnessing the power of occupation become available to those of us with these unique and complex struggles soon. Thank you for publicizing the concept.

Long time listener, first time writer ; )

The movie ‘Session 9’ was filmed at the Danvers State Hospital before it was partially demolished and the building is practically a character in the movie. Really good if you haven’t seen it.

I just wanted to thank you for this episode and for helping me think about a different perspective on the NYS mental health system.

Just so my background and potential bias is clear, we recently discovered that BOTH of my grandparents — Italian immigrants in the early 1920s — had not in fact died in the early 1930s (as we always thought), but were actually involuntarily committed in 1932 (grandfather) and in 1938 (grandmother). Both were initially sent to the Rockland Asylum; my grandmother wound up in Buffalo in 1943 or 1944 and we’re guessing she was there for a good portion of her life.

Even more curiously, we’ve discovered that my grandfather lived until 1990, and my grandmother until 2002, totally unknown to any of us. They are buried in different places (probably just as well given what we’ve learned about my grandfather’s commitment papers) in unmarked graves.

Some, but not all, of the detail I’ve discovered is in the various posts at this link – https://medium.com/@jmancini77_24738. (I didn’t know about the Buffalo part when I wrote these posts.)

One thing that occurs to me in listening to this podcast is that I need to perhaps be a bit more balanced in thinking about my “Shutter Island” and “One Flew Over the Cukoo’s Nest” imagery with regards to Rockland and Buffalo. Clearly the creators of these places were sincerely driven by a Kirkbride-esque desire to improve and humanize care; it is not their fault that Buffalo went from the intended 600 patients to the 3,600 that were characteristic of the time when my grandmother was there, nor are they responsible for the failure of state governments to adequately fund these institutions.

We actually know virtually nothing about what happened to them from their entrance into the system pre-1940 until their deaths — obviously a family medical history concern given that they BOTH were involuntarily committed. Why? The well-intended but absolutely ridiculous New York State Office of Mental Health refusal to release any of the health records for these sad people due to vague “privacy” reasons.

At any rate, thanks for the episode; very thought-provoking.

A very informative article. My grandfather, trained as a homeopathic physician at Philadelphia’s Hahnemann Hospital (later transitioned to allopathic medicine when homeopathy ‘went out of style’) and was Superintendent of the Westboro State Hospital (Massachusetts) for 47 years, 1919-1946. From what I’ve learned from my mother – born & raised there – and her brother – raised there from an early age – it was an extremely humane facility in which the medical staff did their best to enable patients to participate in activities which ranged from the stereotypical basketweaving to working on the farm which provided the greater part of the provisions for the hospital. Those who were judged capable to safely participate in these outdoor activities (including tennis!) were also able to go to the Superintendent’s home and meet with him in his home office. The house was located very close to the main administration building and wards.

The story that really sticks in my mind was that, during the Great Depression, Grandfather Lang authorized commitment of indigent Westborough residents who were not mentally incapacitated but who had no money and no family to take them under care.

As of today, sadly, Westborough State Hospital remains only in memories. The last buildings were demolished in Sept. 2019 and the town of Westborough is building condo apartments for 55+ residents; it appears to be designed for assisted living with group dining rooms etc. but lots of independent living. I think that’s a worthy evolution even though no indigent persons will be able to afford those units.

Your program on the Kirkbride Plan was very interesting, however the closing of the mental health hospitals is half the story. The people released from the hospitals just didn’t evaporate. See the following link for the other half of the story…

https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2016/10/18/13318184/prison-mental-health

Could this be the subject of a second episode?

As I listened to this story, I began to recall memories from when I was a young boy. Each summer in the 1950s, my family would travel to Traverse City, Michigan for a holiday trip. The trips always began with my father and I going to the nearby asylum to buy fishing worms from a man who was a resident. The grounds were beautiful – and mysterious to a boy of ten- but I looked forward each year this to our visit and seeing and talking to the old man with the worms. After listening to this story, I’ve discovered that the Traverse City asylum was, in fact, a Kirkbride institution. Thank you so much for this wonderful piece.

Its unfair to characterize Gould Farm as some incredible new way to treat individuals suffering mental health crises. It sounds more like a transitional residential facility instead of a forensics or mental health hospital. I doubt with their unlocked doors and such that they are catering to individuals with a high acuity, potential self harm, or suicidal thoughts. Plus they charge $350 a day to attend (from their website). No state facility can get away with being so selective about admissions, and often individuals in state facilities are under involuntary commitments. In short, neat facility, but its unfair to paint other mental health facilities dealing with individuals requiring much higher levels of care, or who cannot afford any fees to attend, as somehow inferior.