In 1999, a nature documentary called Wolves came out in IMAX theaters. The film was designed to combat the misinformation campaigns of the ranching and hunting lobbies, which portrayed wolves as vicious killers. The filmmakers wanted to show a wolf pack interacting in complex, subtle ways.

But filming the intimate lives of wild wolves is nearly impossible because they don’t tolerate the presence of people. So the show’s producers went to game farm, “rented” wolves who were more used to being around humans, and constructed an artificial den with cameras inside. And in the movie there are these amazing close-up shots of puppies cozying up against their mother’s belly.

At a screening for the film someone in the audience asked producer Chris Palmer how the team had captured these extraordinary shots inside the den. Palmer’s heart sank, but he decided to come clean, and when he did he could feel the excitement leave the room. Up to this moment, he had assumed people wouldn’t care. “But they do care,” he realized. “They are assuming they are seeing the truth … things that are authentic and genuine.”

Of course, there’s some level of illusion in all film-making. Filmmakers choose their shots and edit footage to form a narrative. In some cases, these illusions can help tell the truth about animals, but not always.

In the film White Wilderness, a documentary produced by Disney in 1958 about the high Arctic, a herd of tiny lemmings approaches a rocky cliff along the ocean. The little furballs peer over the edge and then, one by one, over they go.

It’s a dramatic scene, in which the Lemmings appear to be committing suicide. Except, this entire sequence was staged. The producers took the lemmings to a cliff in Alberta and, in some scenes, used a turntable device to throw them off the edge. Not only was it staged, but: lemmings don’t even do this on their own. Scientists now know that the idea of a mass lemming suicide ritual is entirely apocryphal.

Less egregious acts of deception happen all the time in nature films. Filmmakers sometimes lure wildlife closer to the cameras or harass animals to get them to do something exciting.

And then there’s the question of sound. In most wildlife films, the sounds you hear were not recorded while the cameras were rolling. Most filmmakers use long telephoto lenses to film animals, but there’s no sonic equivalent of a zoom lens. Good audio requires a microphone close to the source of the sound, which can be difficult and dangerous.

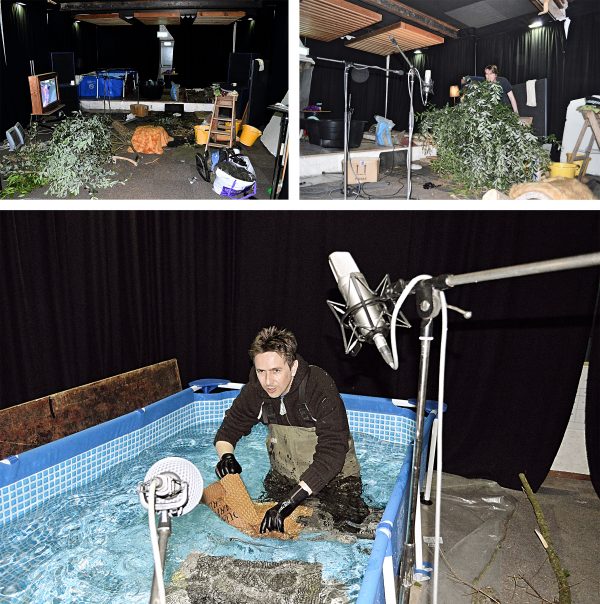

And so many of the subtle movement sounds — a chimpanzee rustling through leaves, or a hippo squelching in the muck, or a lizard fleeing snakes — don’t come from animals at all. They’re made by Foley artists.

A Foley artist’s job is to perform movement sound for a film. Foley artist Richard Hinton works in a windowless room with pits filled with different materials: sand, dirt, gravel, grass. He sits on the edge of the pits and watches a silent version of the scene.

As the animals move, Hinton tries to match their footfalls with his hands. For hooves he will use the tips of his fingers — for lions, the flat side. For more complicated sounds he has a massive collection of objects and materials that he’s collected over the year — sheets of metal, pieces of rubber, old wetsuits.

Foley artists share techniques, and some of their tricks have become so ubiquitous that they have changed our understanding of the way nature actually sounds.

With vocalizations however — growls, grunts or bird calls — filmmakers generally seek sounds that are as accurate as they can be. But even if the sound matches the same species and activity, it doesn’t mean that sound comes from the same exact animal seen on the screen.

Sometimes editors get these sounds from catalogs of animal recordings, but often they hire sound recordists like Chris Watson. Watson usually gets a storyboard from the film’s director, and it’s his job to find sounds that match a particular scene. He has lots of techniques for getting close-up sound without getting too close himself. If he is working on a lion sequence, Watson seeks out a pride and when they have moved to another location temporarily he goes in and rigs his microphones, knowing they will return. Watson once used a long boom to record a cheetah resting beneath a tree. Over the course of an hour, he slowly lowered the boom and captured the animal’s remarkable purr. Watson also records ambient sounds, so that editors can piece together an accurate soundscape.

When he can, Watson likes to record sound while the cameras are rolling to give the film an extra level of realism. In the BBC documentary The Life of Birds, the director asked him to mike up a bunch of trees and bushes where he knew songbirds liked to sing at dawn. And it worked. The birds showed up right on cue, and sang right into his tiny microphones as they filmed. Sometimes, though recording the sound separately can actually enhance the accuracy of the soundtrack. In the BBC documentary Life in the Undergrowth, Watson had to record an amazing sound that this particular caterpillar makes from inside an ant den. It’s the caterpillars attempt to mimic a baby ant to get the adult ants to feed it. Watson recorded the sound by placing these caterpillars on special microphones inside a studio. He never would have been able to capture that sound in the wild.

Sound recordists and Foley artists go to great lengths to give us accurate and satisfying sounds. But both know that nature documentaries are not reality. As much as people want to believe it’s all real, nature documentaries are still movies, and they need a little movie magic just like any other film.

Chris Palmer, the filmmaker who once used rented wolves to show a den scene, believes the movie magic must be employed to tell the truth. One form of deception that he’s concerned about is the tendency to portray the natural world as if it doesn’t have problems. Too many nature documentaries show a world divorced from human civilization, he believes. There are seldom shots of the nearby city, or the coal mine encroaching on habitat. To leave out any mention of these environmental challenges, says Palmer, is misleading.

Filmmaking can be a powerful instrument for showing the natural world and the challenges it faces. But sometimes to tell a compelling story, you will need a bit of fakery.

Comments (13)

Share

Chris Watson! Woot woot!

http://www.macaulaylibrary.org for many natural sounds.

This episode really just blew my mind. I started watching a nature documentary and can just not see it the same way since listening to this episode. Very interesting, keep up the amazing work of illuminating that which we don’t normally see!

How is it a documentary if it is fake? I should be using bad English and all caps as I remove my support, throw my challenge coins in Sutro Baths, and angrily denounce your advocacy of fake documentary.

Is this satire or genuine outrage? (It’s so hard to tell.)

And yes, I was so upset I used incorrect punctuation? I am walking the dogs. I hope the ? here can be swapped for the . in the comment. Greater truth and all that.

I enjoyed this episode, and it reminds me of a related theme. If you know common bird songs, as my wife and I do, and you pay attention to them as you watch popular movies, you will quickly realize that the house wren is (almost) “the only bird in Hollywood” — its song is often placed in the background in outdoor scenes, often totally out of place. That’s mostly not too disruptive, but then there’s the tense scene in the 1991 movie Black Robe where (as I recall) one of the white men is being lethally stalked by Iroquois in the late autumn forests of southern Canada — and then a hermit thrush sings, totally shattering (for those of us who know birds) the reality of the scene. Sorry, but hermit thrushes are long gone by then, well on their way to their winter habitats in South America. I have often wondered if there are any “natural history continuity” consultants in Hollywood to deal with these kinds of problems. Who speaks for the birds?

Interesting comment.

Planet Earth II episode in Cities addresses the last point perfectly.

Great episode! It really blew my mind too. Thank you very much.

Many of the anecdotes in this story are true. But I think one of the flaws of this story is that it makes a lot of generalizations. There are in fact lots of natural history film makers that go out of their way to be honest with what they film and record. Many natural history broadcasters have ethics guides for productions (http://www.bbc.co.uk/editorialguidelines/guidance/natural-world/guidance-full) and even festivals have started to challenge film makers on whether they have fabricated the story.

Its true sometimes you cannot get location audio but I find that those situations are rarer and rarer. I always record ambient audio at least to form part of a background. Despite what the story said there are lots of pretty good shotgun mics that can pick up sounds except on windy days. In many cases remote microphones and standalone audio recorders can be set up in advance and the crew can be far away. People have filmed picture and audio of coyotes using motion detection. I have run audio and picture deep into bird burrows while they were at sea and been able to get amazing footage and sound of egg laying and hatching. My point here is that unlike what was presented in the story there are lots of ways to get real picture and sound and the times when you cant are fewer and fewer.

Of course one exception for many crews is that on one hand drones have opened up a new world of footage (unless filming in bird sanctuaries or nesting areas) the trade off is that generally the audio has the sound of the drone in it.

Unlike what was stated in the show I find most natural history docs that are seen today are all about human impact. A look at any of the major natural history festivals reveals very few films that present a natural world without human impact or at least a mention of climate change. I cat recall the last time I saw a natural history film that did not at least nod to human impact in the VO if not not actually showing it. I would also like to add that I have seen a few major elephant docs over the past few years where there was no stomping foot sound at all so one again the comments in the show are generalizations.

Lastly I respect of work and opinions of my natural history brothers and sisters but felt I had to comment. Cheers.

I really like to come to the forest and hear natural sounds.

I like to listen to natural sounds and relaxing music along with that.