In the mid-1800s, not many (non-native) Americans had ever been west of the Mississippi. When Frederick Law Olmstead visited the west in the 1850s, he remarked that the plains looked like a sea of grasses that moved “in swells after a great storm.” Massive herds of buffalo wandered the plains. Cowboys shepherded cattle across long stretches of no man’s land. It was truly the wild and unmanaged west, but it was all about to change, due, in large part, to one very simple invention that would come to be known as “the devil’s rope.”

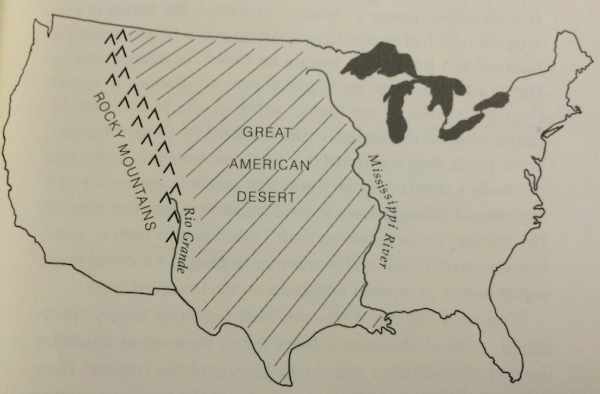

From the colonial era through the early 19th Century, the middle of the United States was populated mainly by Native Americans and a growing population of cowboys, or “cattlemen” as they were often called. Most of the American west was divided into “territories” and, apart from Texas, most of the land was owned by the federal government. The middle swath of the country was so unexplored that it was often labeled on maps as “The Great American Desert.”

Then in the mid-1800s, a notion of manifest destiny swept the nation—the idea that the United States could, and should, span coast to coast. The U.S. government wanted farmers to move west, because farmers, unlike cattlemen, would establish communities and build permanent settlements. In 1862, President Lincoln signed the Homestead Act, offering 160 acres of free land to anyone who settled and farmed it for five years.

Would-be settlers started heading west in droves but they quickly encountered a problem: fencing. In that great “sea of grasses,” there weren’t many trees to use for lumber, so although the land was fertile, there was no way to stop the many cattle from trampling and destroying crops.

Farmers tried using thick and thorny Osage orange hedges for fencing, but they take about five years to grow, making them largely impractical.

Settlers also tried smooth wire fencing, but the cattle could bust through it. People were getting frustrated; many abandoned their homesteads.

Fencing became a hot topic among newspapers, agricultural publications, and the government. The U.S. Department of Agriculture the Land Office published a study in 1871, which found that it was impossible to settle the west because of a lack of fences.

But then came the solution: barbed wire.

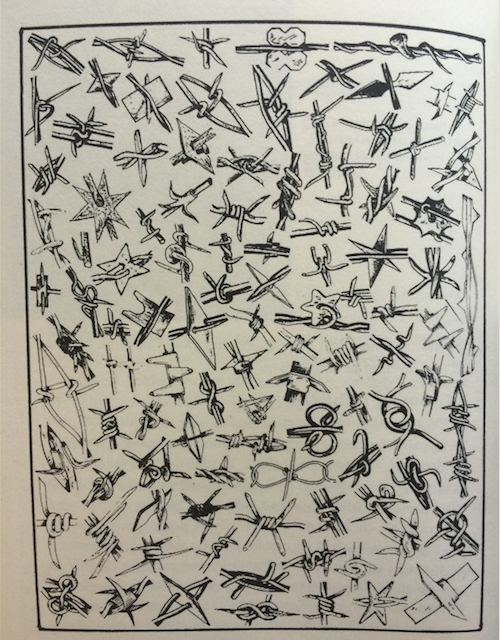

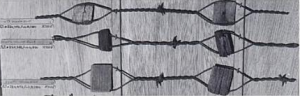

Many different patent applications for barbed-wire-like fences were filed around this time. The below image shows some of the various designs:

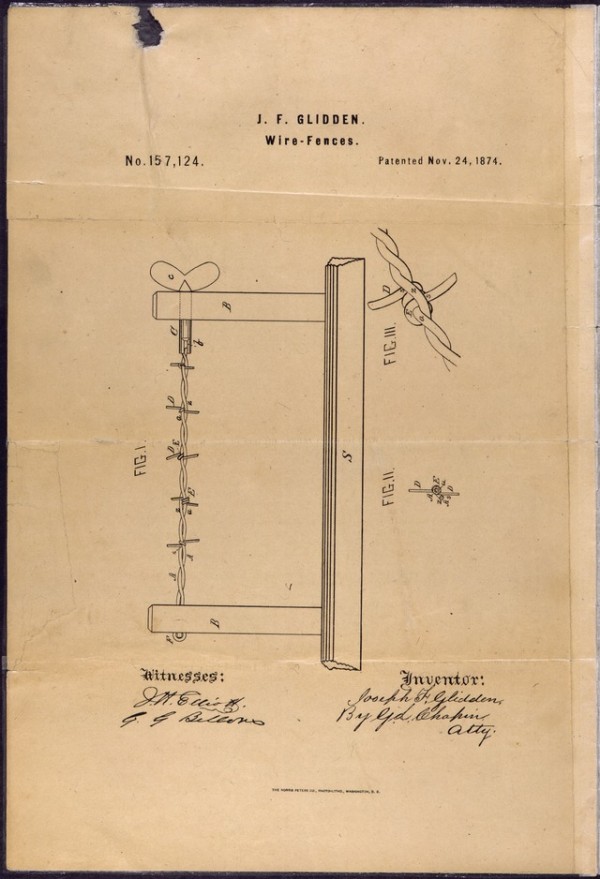

But the barbed wire design that ultimately won-out and caught on was by Joseph Glidden. His design had sharp metal barbs twisted around a strand of smooth wire, with a second intertwined piece of wire so that the barbs couldn’t slide around.

Glidden’s design took off, and by 1876, his company was producing nearly three million pounds of barbed wire annually.

Before barbed wire divided up the west, the cattlemen had mostly been watching and laughing as the farmers struggled with their shrub-fencing. Before the settlers arrived, the west operated under “the law of the open range.”

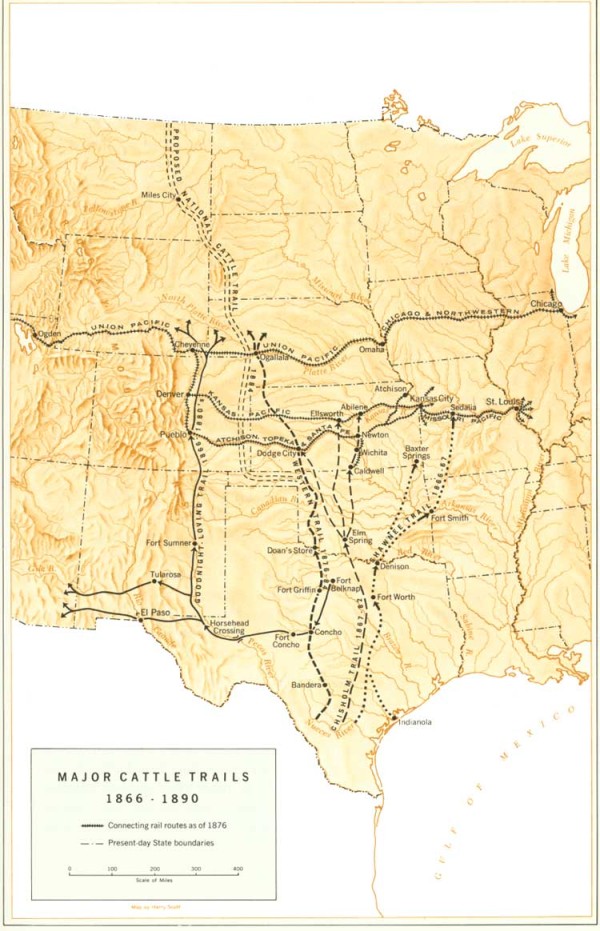

Though it was never officially legislated, “the law of the open range” was respected and understood widely in the west. Cattlemen needed the land to be open so that cattle had access to grazing lands and water. This was especially true during the long trail drives cowboys did to move cattle to larger cities where they’d be put on trains for export to the east coast.

Barbed wire fences were in direct contradiction to “the law of the open range” and also could injure or maim cattle. There were attempts to design a more “humane” barbed wire – it was made to be easier for cattle to see and avoid, but it didn’t catch on.

In any case, the cattlemen weren’t happy, and relations became tense between farmers and cattlemen.

The musical Oklahoma! even has a song about this tension, “The Farmer and the Cowman”:

The chorus of the song implores all “territory folks” to stick together, but in reality, cowboys and farmers wouldn’t become friends for a while. The cattlemen resented the farmers as they put up more and more fences. And that’s what led to the fence-cutting wars.

In 1881, cattlemen started cutting down fences that farmers were putting around the land that they didn’t have a rightful claim to. The cattlemen cut fences at night with masks on, and they formed fence-cutting gangs with names like The Owls, The Blue Devils, and The Land League. Eventually, the gangs would start cutting legally-erected fences as well. Most of the damage thereof was in property value, but a few shooting deaths were attributed to this feud.

Eventually, the federal government and the state of Texas intervened, and the fence cutting died down around 1885.

But the fencing off of the west didn’t just disrupt the cow population—it also had an effect on buffalo herds. During the 1800s, the buffalo that roamed the American West died off in huge numbers, in part because settlers were killing them for their hides, but also because barbed wire impeded the buffalo’s access to grazing lands and water.

Before white people lived in the west, there were an estimated 65 million buffalo roaming the plains. By the end of the century, there were fewer than a thousand.

The extinction of the buffalo, in turn, ruined an entire way of life for the Native American tribes that followed the migration of the buffalo. Native Americans ultimately came to refer to the wire as “the devil’s rope.”

By the end of the century, the west was covered in “the devil’s rope,” And shortly thereafter, Europe would also be covered in it, but in a very different context. In World War I, barbed wire would become infamous in trench warfare; in World War II, barbed wire became the emblem of concentration camps.

Barbed wire’s history has mostly been about control, possession, and separation but there is one instance where barbed wire was used not to separate us, but to connect us.

Right around the same time that barbed wire was invented, Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone. At first, telephone companies were laying telephone wire in cities, but they weren’t interested in the rural market. Still, farmers also needed phones, which meant that they needed a network of wires to connect the farms. Barbed wire fences could serve this purpose. The barbed wire couldn’t transmit a signal quite as clearly as a nice insulated copper wire, but for many years, they did the trick. A dozen or so farms might be connected on one system and for about 25 dollars, farmers could buy a kit to rig themselves into the network. In 1907 there were 18,000 independent telephone cooperative serving nearly a million and a half people. Because of this, farmers were some of the earliest adopters of telephone technology.

By the 1930s, the national Bell Telephone system had penetrated into the remote rural regions of the West and Midwest. Farmers no longer had to create their own telephone collectives, and barbed wire went back to doing what it does best: keeping us in, keeping us out.

*An earlier version of this article included an image that was incorrectly identified as an Osage Orange.

Comments (24)

Share

It is possible that the tree depicted in your photo of Osage Orange is a real variety of orange (or at least citrus) that goes by that name, but it does not appear to be the plant called Osage Orange that was used for hedges, which is *not* a citrus. That one is also called hedge apple. Though its fruit doesn’t look much like an apple, either.

http://www.gpnc.org/osage.htm

http://www.na.fs.fed.us/pubs/silvics_manual/volume_2/maclura/pomifera.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maclura_pomifera

Yet again another wonderful piece about a historical design that had more uses than I could have possibly imagined especially the part about running a telephone signal through the wire. keep up the wonderful work I’ve enjoyed your program from the very beginning.

I still remember a 9th grade science assignment where we had to choose the single more influential invention/development in technology. I chose wire and this gives me some vindication, as well as a wish this episode had been around back then. Thanks for a great piece!

As a born Kansan, it is my duty to inform you that no buffalo exist (outside a zoo) in the United States. What you are calling ‘buffalo’ is the actually the American bison. The two species have no relation. It would be like mistaking a tomato for a vegetable.

Hi Quint, Yeah we struggled with what to call them — you’re right ‘bison’ is the correct term, but what we found is that ‘buffalo’ is also an acceptable, though more colloquial name, and since our main guest referred to them as ‘buffalo’ we decided to follow suit. Here’s what wikipedia says about the name.

The term “buffalo” is sometimes considered to be a misnomer for this animal, and could be confused with two “true buffalo”, the Asian water buffalo and the African buffalo. However, “bison” is a Greek word meaning ox-like animal, while “buffalo” originated with the French fur trappers who called these massive beasts bœufs, meaning ox or bullock—so both names, “bison” and “buffalo”, have a similar meaning. The name “buffalo” is listed in many dictionaries as an acceptable name for American buffalo or bison. In reference to this animal, the term “buffalo”, dates to 1625 in North American usage when the term was first recorded for the American mammal.[13] It thus has a much longer history than the term “bison”, which was first recorded in 1774.[citation needed] The American bison is very closely related to the wisent or European bison.

fascinating article! and very cool to learn something new in the “comments” section, rather than the customary degeneration into off-topic pettiness that abounds online. thanks so much for commenting and for the valuable explanatory response. my first time looking around here, and I plan to continue following :-)

The “L” in Dekalb, IL is not silent.

This is true. I came here to leave just this comment. In Illinois we don’t drop the L like they do with the county in Georgia

Barbed wire fencing was being used to transmit communications between left-wing guerrilla fighters in the El Salvador civil war as recently as the early 1990s. They also used this method for their revolutionary radio station ‘Radio Venceremos’ (‘We Shall Overcome’ Radio).

Don’t forget about the great Cole Porter song, “Don’t Fence Me In”!

Nice to see that the Osage Orange photo has been corrected…

This was a great podcast! We listened to it while driving through West Texas and Eastern New Mexico–perfect landscape for this story. I wrote it about and linked to your podcast.

http://www.bluejeansandturquoise.com

Really good episode. The turn at the end about how the fencing network was used for early telecommunications was something I had never heard before. And coming as it did at that point in the story, it actually kind of made me tear up a little bit.

Good to hear the story of barbed wire as a Huskie (alum from Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, IL). You can still find Anne Glidden Road and the Ellwood House there among other barbed wire related things. Thanks for the great piece!

Loved the episode! One note: you set the scene perfectly with the evocative narration from Lonesome Dove, but I don’t remember hearing the name of the author, Larry McMurtry! Seems like he deserves a shout-out.

Probably one of my favorite episodes.

I never liked barbed wire much but the day an overgrown stretch of it ripped all the skin off my beloved horse’s hind leg I was ready to outlaw the stuff. The horse eventually recovered after many many stitches and a lot of rest but I’m not sure I did. I will always remember that day as one of my more traumatic teenage episodes.

I’d forgotten about the day that it almost cut my cousins life short. She was riding a snow machine, and rode into a section of Barbed wire. It looked like she’d gone through a harvester. She’s survived, and shows no scars, Praise the Lord, but it sure was frightening ar the time.

Roman Mars: Larry McMurtry. A novel is no more an “it” than a radio show. Somebody has to make it.

Folks: Nice article If those who believe that the buffalo were in any way deterred by the rustic salvaged branch-type post scuffed into the ground with bob wire stapled or wired onto the post, a visit to the west is needed. Ask any rancher today what elk herds do to fencing. The buffalo has a way tougher hide than elk as well as the body mass[impact effect] in their herd behavior vs the elk herds which decimate many yards of fence line at will even with modern fence. Fencing can be built to contain them today, but not back in the day for the hard scrabble farmers of that era…….

Loved this episode! Thank You.

Fantastic episode – the usual excellent 99pi stew of people, things and places.

Please ignore if this is old news to people, but I thought I should clear up Ye as in “Ye Old…”

It was originally (1500s etc.) “The Old…” using a single character for the “Th” called thorn. It looks confusingly like a Y – I have seen versions where it has a straight vertical line, with another shorter line going up at about 30 degrees from half way up the longer line. Even though it looked like an asymmetric Y it was pronounced “th”.

More confusingly, around the same time, “ye” was used as a form of “you”. As in the King James Bible from 1611 such as Matthew 7:16 – “Ye shall know them by their fruits. Do men gather grapes of thorns, or figs of thistles?”

Given the presence (at least in places like the old UK village where I work) of buildings like The Old Carpenter’s Shop, The Old Schoolroom etc. which are now homes, and pubs like The Farmers’ Arms, I look forward to people in the future living in The Old Data Centre and drinking in The Programmers’ Arms.

(Sorry this is much later than the episode; I am 2/3 of the way through catching up with old episodes!)

“During the 1800s, the buffalo that roamed the American West died off in huge numbers, in part because settlers were killing them for their hides, but also because barbed wire impeded the buffalo’s access to grazing lands and water.”

The buffalo didn’t just “die off”, they were actively hunted to extinction by domestic and commercial hunters, and by the military. If it’s important to talk about how barbed wire changed the West, it’s equally important to be honest about the other events of the time.

Also, I’m not sure barbed wire had that much effect on bison herds: “This agility and speed, combined with their great size and weight, makes bison herds difficult to confine, as they can easily escape or destroy most fencing systems, including most razor wire.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_bison)